The History of the School of Physics

The history of physics at Trinity College Dublin (TCD) spans more than three centuries and mirrors the evolution of physics as a scientific discipline in Ireland. From its beginnings in the late seventeenth century to its emergence as a modern research-driven department, the School of Physics at Trinity has been shaped by scientific advances, institutional reforms, and broader social and political change. The department has been home to several prominent figures in the history of science, including Richard Helsham, Humphrey Lloyd, George Francis FitzGerald, and Ernest Walton.

/filters:format(webp)/filters:quality(100)/prod01/channel_3/media/tcd/physics/images/1906-fitz-building.jpg)

Image above: The Fitzgerald Building 1906

Early Foundations (1592–1683)

Although Trinity College Dublin was founded in 1592, physics as a formal subject was not taught until the late seventeenth century. The early curriculum was dominated by Aristotelian philosophy, but the Reformation and the rise of empirical science gradually altered the intellectual landscape.

A key figure in these early years was William Molyneux (1656–1698), a TCD graduate who founded the Dublin Philosophical Society in 1683 and wrote Dioptrica Nova (1692), the first English-language book on optics. He is also remembered for posing the philosophical “Molyneux Problem” concerning perception. Another early Trinity physicist was Narcissus Marsh, Provost from 1679 to 1683, who made contributions to acoustics and coined the term “microphone.” He later founded Marsh’s Library in 1707.

The 18th Century: Institutionalisation of Physics

The eighteenth century saw the creation of the first building associated with physics at TCD. In 1710, it was decided “that ground be laid out in the south-east corner of the physick garden sufficient for erecting an Elaboratory and anatomical theatre thereupon.” The so-called “Anatomy House”, located near the south-east corner of the Old Library (where the Eavan Boland Library now stands), included a chemical laboratory, lecture room, dissecting room, and museum. It was likely used for teaching in Natural Philosophy (Physics), Chemistry, Botany, Physic (Medicine), and Anatomy.

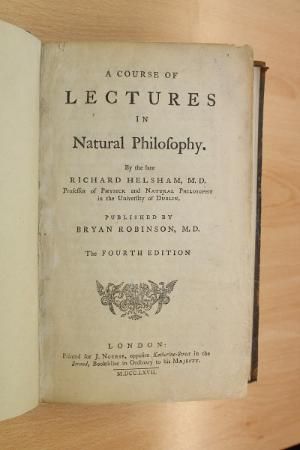

The Erasmus Smith’s Professorship of Natural and Experimental Philosophy was established in 1724, marking the formal recognition of physics as a discipline at Trinity. Richard Helsham, the first holder of the chair, was a polymath and physician. His Lectures on Natural Philosophy (1739) was the earliest textbook on Newtonian physics written specifically for undergraduates. Widely used in Dublin and Cambridge, it remained required reading as late as 1849 and was republished to celebrate the millennium. In Helsham’s time, the instrument collection numbered hundreds of items—many of which date from the late nineteenth century. One item that survives from the 18th century is a lodestone which was presented to Helsham, and is a splendid emblem of our modern research in magnetism. It is currently in display in the Fitzgerald Library.

The 19th Century

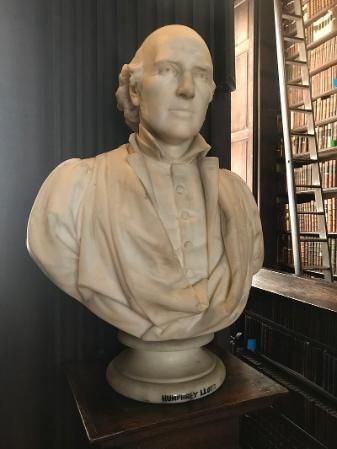

The nineteenth century marked a golden age for physics at Trinity. Under Provost Bartholomew Lloyd, the curriculum was reformed, and honours degrees (“moderatorships”) were introduced. His son, Humphrey Lloyd, became Erasmus Smith’s Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy in 1831. Lloyd’s experimental work provided crucial confirmation of Hamilton’s theoretical prediction of conical refraction, validating Fresnel’s wave theory of light. He also designed instruments for geomagnetic studies and oversaw the construction of the magnetic observatory in 1837. As Provost, he established the Engineering School in 1841 and introduced the first science moderatorship in experimental physics in 1850.

Bust of Humphrey Lloyd on display in the Long Room in TCD

The title page of "A Course of Lectures in Natural Philosophy" (4th edition).

Many of the advances made in Trinity during this period were in the field of mathematical physics. In this area, James MacCullagh was appointed Erasmus Smith’s Professor of Mathematics in 1838 and was the 11th Erasmus Smith’s Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy from 1843 until his death in 1847. He was a leading expert in analytic geometry, calculus, mechanics and optics. In 1830 he published an improved analysis of wave propagation in biaxial crystals, foreshadowing Hamilton’s discovery of conical refraction. MacCullagh introduced the concept of complex refractive index to describe optical absorption. His work on light propagation in crystals allowed him to conclude that the perturbation of the ether by light had to be rotational in character. Arising from this work, he invented the mathematical operator known as the curl of a vector field. In 1839 he succeeded in deriving a differential equation for light, two decades before James Clerk Maxwell.

In 1881, George Francis Fitzgerald was appointed Erasmus Smith's Professor. He championed the electromagnetic wave theory of light, suggested that an oscillating electric current produces electromagnetic waves and was first to propose that nothing could move faster than light. He is most famous for suggesting the length contraction which appears in Einstein’s theory of special relativity. FitzGerald was a widely influential figure as the leader of the international team who called themselves the Maxwellians. He was elected a member of the Royal Irish Academy in 1878, and the Royal Society in 1883. In 1899, he was awarded a Royal Medal for his work. A number of his assistants went on to become renowned physicists, notably John Joly and Frederick Trouton. His uncle, George J Stoney, another Trinity graduate, gave the electron its name, before it was experimentally discovered.

George Francis Fitzgerald flying in College Park in 1895

Early 20th Century (1901–1946)

After Fitzgerald's death in 1901, the department entered a period of relative stagnation. Erasmus Smith’s Professor William Edward Thrift focused mainly on administrative duties, and research activity slowed. However, largely due to Fitzgerald's earlier advocacy and Joly’s energeric fund raising, plans were laid to build a new physics building for the college. The Physical Laboratory (now the Fitzgerald Building) was completed in 1905 with funding from Lord Iveagh. It housed lecture theatres and laboratories and became the centre of physics in TCD.

In 1929, Robert William Ditchburn was appointed Erasmus Smith's Professor and initiated major reforms. He modernised the curriculum, recruited new staff, and promoted undergraduate research. Ditchburn also provided positions for Jewish refugee scientists fleeing Nazi Germany, including Alfred Bloch and Hans Motz. Bloch was notable in having developed the first piezoresistive composites and demonstrating their use as strain gauges, a research area that is still active in the school 90 years later. Other notable staff during this period included J.H.J. Poole, a researcher in radioactivity and geophysics and his brother H.H. Poole who first reported the phenomenon now known as the Poole-Frenkel effect.

However, the most notable academic of this time was Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton. After earning his undergraduate degree in TCD, Walton won an 1851 Research Fellowship to study for his PhD under Ernest Rutherford in Cambridge. In 1932 Ernest Walton and John Cockcroft built a particle accelerator in Cambridge to split the nuclei of lithium atoms by bombarding them with a stream of accelerated protons to produce helium nuclei. They were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1951 for “their pioneer work on the transmutation of atomic nuclei by artificially accelerated atomic particles”. Walton is the only Irish Physics Nobel Laureate to date.

E.T.S. Walton in 1951

In 1940, Taoiseach Éamon de Valera founded the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies (DIAS) and invited Erwin Schrödinger to head its School of Theoretical Physics. Schrödinger delivered his influential What is Life? lectures in the Physics Lecture Theatre in the Fitzgerald building in 1943. Crick and Watson later cited Schrodinger's lectures as the inspiration for their work on the structure of DNA.

Post-War Period (1946–1974)

Having returned to Trinity College Dublin in 1934, Walton succeeded Ditchburn to become the 18th Erasmus Smith’s Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy in 1946. That same year, Joyce Power-Steele was appointed assistant to the Erasmus Smith Professor, becoming the first female academic staff member in physics at Trinity. The department expanded its facilities, adding a Van de Graaff accelerator and a new laboratory wing funded by Sir Hugh Beaver. Research areas included nuclear physics, radiocarbon dating, and spectroscopy. Theoretical physics became a separate moderatorship in 1966, reflecting the discipline’s growing importance.

Expansion and Modernisation (1974–1999)

Following Walton’s retirement, Brian Henderson became Erasmus Smith’s Professor in 1974. Under his leadership, staff numbers and research output grew significantly, and the FitzGerald Medal and Walton Prize were established to recognise student excellence. Henderson recruited outstanding scientists, including Daniel Bradley FRS and future Fellow of the Royal Society Michael Coey. This period marked the start of a new era of interdisciplinary and international research.

Michael Coey joined Trinity in 1978, later becoming Erasmus Smith’s Professor. A global authority on magnetism and spintronics, his pioneering work on permanent magnets, thin films, and multilayer materials underpined technologies from renewable energy to data storage. He co-discovered the magnetic compound Sm₂Fe₁₇N₃, helped found the CRANN Nanoscience Research Centre, and co-founded Magnetic Solutions. A Fellow of the Royal Society (2003) and Foreign Associate of the US National Academy of Sciences, Coey received numerous honours, including the RIA Gold Medal and the Max Born Medal.

Daniel Bradley was appointed as Professor of Optical Electronics in 1980. At Trinity he shifted his research focus from fundamental laser physics to applications of dye-lasers in biology and communications, helping establish Ireland as a hub in ultra-fast photonics. His pioneering work on picosecond pulses and non-linear optics paved the way for modern femtosecond lasers and optical telecommunications. Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and member of the Royal Irish Academy, he left a legacy of innovation and mentorship before retiring on health grounds in 1984.

Henderson was succeeded as Erasmus Smith’s Professor in 1984 by Dennis Weaire, a computational physicist whose research spanned crystalline and soft matter systems. Weaire discovered the “Weaire–Phelan structure,” the most efficient way to partition space into equal cells with minimal surface area—famously used in the design of Beijing’s 2008 Olympic Aquatic Centre. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1999.

Into the New Millennium (2000–Present)

From 2000 onward, the School entered a period of rapid expansion, growing from 14 academic staff in 1999 to around 30 by 2025. This growth was driven by national investment in science through Science Foundation Ireland (founded in 2003) and increased government funding. Research diversified into new areas including nanoscience, astrophysics, and quantum technology.

The School expanded physically with the Sami Nasr Institute of Advanced Materials (SNIAM), shared with Chemistry and Engineering built in 2000. It also played a central role in founding the Centre for Research on Adaptive Nanostructures and Nanodevices (CRANN) and the Advanced Materials and BioEngineering Research Centre (AMBER). Both are housed in the Naughton Institute and provide state-of-the-art research facilities.

The School of Physics Today

The School of Physics at Trinity College Dublin is now one of Ireland’s largest and most vibrant physics departments, with around 30 academic staff, more than 50 post-doctoral researchers and over 100 postgraduate research students. Our research spans world-leading areas including magnetic, electronic and photonic materials, nanoscience, quantum science, computational physics, astrophysics and energy science. We work in purpose-built facilities such as the Centre for Research on Adaptive Nanostructures and Nanodevices (CRANN) and the Sami Nasr Institute of Advanced Materials, enabling interdisciplinary research collaborations across physics, chemistry and engineering. On the teaching side, the School offers a suite of honours degree programmes, Physics, Physics & Astrophysics, Theoretical Physics (in collaboration with Mathematics), and Nanoscience (in collaboration with Chemistry), each accredited by the Institute of Physics and designed to equip students with strong foundations in experiment, theory and computation. Through research-led teaching, international partnerships and strong industry links, the School prepares its graduates for careers across academia, industry, government and beyond, contributing significantly to both scientific knowledge and innovation in Ireland and internationally.

Academic staff in the School of Physics

Prior to 1900, the academic staff members of the School consisted almost solely of the Erasmus Smith’s Professors of Natural and Experimental Philosophy. These are listed below. Since then the academic staff cohort has broadened to include various other groups such as Professors assistants, lecturers and junior professors. Currently, the academic staff are graded as Assistant Professors, Associate Professors, Professors in Physics and Professors of specific areas, for example, Professor of Photonics. A comprehenisive list of academic staff members since 1900 can be found here.

A list of Erasmus Smith's Professors of Natural and Experimental Philosophy can be found here.

Listed below are the Professors of Physics and the Heads of School over the years.

Professors of Physics

- 1934 J.H.J. Poole, Professor of Geophysics

- 1966 C.F.G. Delaney, Professor of Experimental Physics

- 1976 V.J. McBrierty, Professor of Polymer Physics

- 1980 D.J. Bradley FRS, Professor of Optical Electronics

- 1980 J. Hegarty, Professor of Laser Physics

- 1987 J.M.D. Coey FRS, Professor of Experimental Physics

- 2002 J.B. Pethica FRS, SFI Research Professor

- 2002 I.V. Shvets, SFI Research Professor

- 2002 S.P. Jarvis, SFI Research Professor

- 2003 W.J. Blau, Professor of Physics of Advanced Materials

- 2007 J.F. McGilp, Professor of Surface and Interface Optics

- 2007 I.V. Shvets, Professor of Applied Physics

- 2011 J.N. Coleman FRS, Professor of Chemical Physics

- 2012 S. Sanvito, Professor of Condensed Matter Theory

- 2016 V. Nicolosi, Professor of Nanomaterials and Advanced Microscopy

- 2018 J.F. Donegan, Professor of Physics and Applications of Light

- 2019 O. Hess, Professor of Quantum Nanophotonics

- 2025 A.L. Bradley, Professor of Photonics

Heads of Physics

Prior to 1989, the Head of Physics was always the Erasmus Smith Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy

- 1989 J.M.D. Coey FRS

- 1992 J. Hegarty

- 1995 J.F. McGilp

- 1998 W.J. Blau

- 2003 D.L. Weaire FRS

- 2005 J.G. Lunney

- 2008 J.F. Donegan

- 2011 J.G. Lunney

- 2014 I.V. Shvets

- 2020 J.N. Coleman FRS

/filters:format(webp)/filters:quality(100)/prod01/channel_3/media/tcd/physics/images/schrodinger-lecture-21.jpg)