“Are we not all someone’s child?”: Rethinking Chinese Childhood

The protection of the rights of children against exploitation is an issue that spans national borders and boundaries. At Trinity College Dublin, research is ongoing into political and cultural practices that jeopardise or remove children’s experience of a safe and secure childhood.

The protection of the rights of children against exploitation is an issue that spans national borders and boundaries. At Trinity College Dublin, research is ongoing into political and cultural practices that jeopardise or remove children’s experience of a safe and secure childhood.

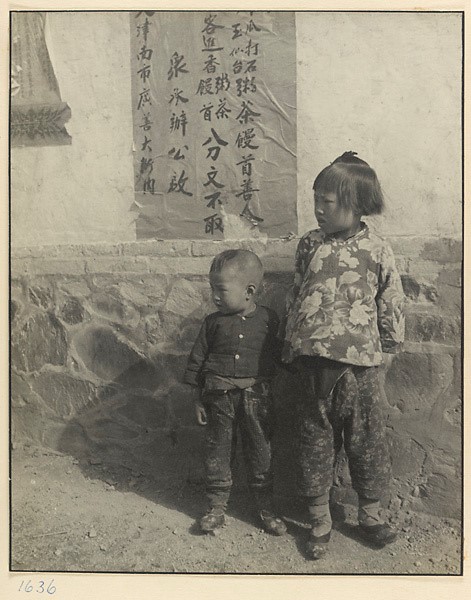

Dr Isabella Jackson, from the Department of History, is leading new research into how, for centuries in China, there was a widespread practice of children being sold by poorer families to rich families. Children were perceived as the property of their parents, without the same rights or humanity as adults.

Girls, particularly, were victims of this, due to the greater importance assigned to boys in Chinese culture. Girls were sold into unpaid domestic labour, making them essentially slaves. Dr Jackson is examining how controversies over unpaid domestic servants reflect changing and expanding conceptions of Chinese childhood. Her Irish Research Council Laureate Award-funded project, “CHINACHILD”, explores changing conceptions of Chinese childhood in the twentieth century, focusing particularly on the Republican era (1912-1949).

China’s Republican era began with the overthrowing of the Qing dynasty in 1912, ending 5,000 years of imperial dynasties in China. The practice of the buying and selling of young girls was entrenched in the culture at this time, even though slavery was technically illegal, with a system of brokerage established through a matchmaker. In some instances, as well as obtaining cash for selling the girl, the poorer family also saw the exchange as a form of “societal improvement” for the girl and the notion that better opportunities might be available when living with wealthier families. However, girls were often sold multiple times, regularly mistreated, and many became concubines or prostitutes.

By the late 1920s, opposition to this practice had become more pronounced, and it was explicitly declared illegal. In Shanghai, administrative offices became more forthright in speaking out against the practice. Attitudes towards children were changing, with an increased emphasis on recognising a child’s right to an innocent and free childhood. However, initially it was boys and elite girls who benefited from this cultural shift. The political campaigns developing in the 1930s signified a shift in the thinking on childhood more broadly in China, in which girls, particularly those from poorer families, slowly began to be considered with greater empathy and with a recognition of their entitlement to safety and security.

Dr Jackson’s CHINACHILD project takes an interdisciplinary, investigative approach, seeking to uncover the histories of girls who usually did not have a voice and did not leave records or sources themselves. There are few oral histories left by the women who were sold in childhood. But there are also court records, including disputes over contracts regarding the sale of children. There are Government authority records, which highlight the contradictions and informal processes around this practice as, although slavery was illegal, families were being instructed to register the sale or purchase of child slaves.

Seeking to draw on archival as well as literary sources, a postdoctoral researcher and PhD student have joined Dr Jackson in this research: Yushu Geng, whose PhD research at the University of Cambridge examined discourses of obscenity and moral regulation in Singapore and China in the 1920s and 1930s, and current PhD student Ka Lo Yau, who is examining the themes of childcare centres, children’s diaries, play, and sports as focal points through which to analyse the interplay between adults’ expectations and children’s subjectivities. The CHINACHILD project is exploring how childhood has been changing in the Chinese cultural and political consciousness.

Dr Jackson’s post was the first professorship in Chinese History in Ireland. She took this position in 2015 after lecturing at the Universities of Aberdeen and Oxford. She says she was lucky that there was a “growing interest in China as a global power,” and she attributes securing the post in Trinity as “a mixture of good timing and going for opportunities as they presented themselves.” Her journey towards this position is an interesting and varied one: She studied History as an undergrad at Bristol then did an MA there in Colonial History and went to Oxford to study for an MPhil in Modern Chinese Studies. This included Chinese language study at Peking University, and she studied Chinese further in Taipei. She returned to Bristol for her PhD, and lived in Shanghai for a year while conducting her research, completing her PhD in 2012. Her monograph was published by Cambridge University Press in 2018, focusing on “transnational colonialism” in Shanghai and how China’s experience of colonialism shaped its past and present.

Dr Jackson is very active with the Trinity Long Room Hub, hosting events to share recent scholarship, including giving talks herself on evolving attitudes to childhood and children in China. The so-called “one-child policy” in place in China from 1978 to 2016 could be very draconian and resulted in a large sex imbalance in children, with around 116 boys for every 100 girls. The traditional preference for male heirs, especially in rural areas, to carry on the family name, inherit land, provide for elderly parents and honour their ancestors, meant that having only one child, if she were a girl, was often considered undesirable. As a result, there was an increase in abortions of female foetuses (even though this was technically illegal), giving girls up for adoption, or keeping daughters unreported so they had no access to education or healthcare.

Less well known, however, is that where parents’ only child was a girl, they often invested much more in her education than they might have had they had sons too. Children, always appreciated in China and often referred to affectionately as “little friends”, have become more cherished than ever in Chinese families as they are frequently the only child and grandchild.

Less well known, however, is that where parents’ only child was a girl, they often invested much more in her education than they might have had they had sons too. Children, always appreciated in China and often referred to affectionately as “little friends”, have become more cherished than ever in Chinese families as they are frequently the only child and grandchild.

The CHINACHILD project has received funding for five years, though the COVID-19 pandemic has presented some roadblocks for the research, including a lack of opportunity to travel to China and access archives. However, Dr Jackson says that the widespread new practice of holding events online has granted them access to discussions that would normally have been more difficult to attend. An example is this seminar on the International History of East Asia, hosted by Oxford University, in addition to other events in the Universities of Glasgow and Hong Kong, and the Institute for Historical Research in London.

For academics in her position, Dr Jackson says, carving out the time for research is increasingly difficult and essential, given teaching and administrative commitments, supervising PhD and Masters students, as well as real-life responsibilities. On balancing motherhood with academia, she says that “you can do both,” but the balance is difficult to achieve.

“Covid has certainly caused problems, both because I have been working while sharing the care of my one year-old son with my husband at times when we've been without formal childcare, and because I haven't been able to access the archives that I planned to visit.”

She highlights the demands on early-career researchers and the precarity of early-stage academic life, emphasising the importance of considering “what is a good use of your time,” especially for PhD students, whom she points out are vulnerable to exploitation. She highlights the value of public engagement for academics, and the obligation to educate the public with evidence-based research, particularly during a time of “fake news” and misinformation.

Dr Jackson’s expertise on China historically and today has been sought by Irish news outlets including The Irish Times, The Business Post and RTÉ on issues such as the crackdown on democracy in Hong Kong, the oppression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, and Chinese attempts at censorship in Ireland. She featured in a TV documentary series An Misean sa tSín (Mission to China), providing historical context for the presence of Irish missionaries in twentieth-century China, reaching more than 100,000 viewers. Internationally, she has been interviewed and quoted by BBC World News, the Washington Post and El Paíson Chinese views of their own national history.

It is essential, she states, to share research on China rather than just “opinion” on China. However, she suggests that the UK REF system has enforced a problematic system in which research is driven by the need for impact rather than recognising that impact arises organically from research in ways that cannot necessarily be predicted.

Dr Jackson and her team are organising a Virtual Conference on Friday May 21st, 2021 entitled Rethinking Chinese Childhood in Modern History. The conference will explore changing attitudes towards girls and childhood in China, from the traditional view of raising girls to be good wives and mothers to a broader investigation of the political and cultural context, as reflected through the nation’s children. For more information, check out the CHINACHILD website.

Article by Dr Kate Smyth, Consultancy Development Officer, CONSULT Trinity, Trinity Research and Innovation.

For more information on academic consultancy visit CONSULT Trinity

Find out more about writing for researchMATTERS here.

All images taken, with thanks, from Historical Photographs of China (HPC), University of Bristol (www.hpcbristol.net).

Image 1: Photograph by Hedda Morrison, image courtesy of President and Fellows of Harvard College and HPC (HPC ref: Hv27-11).

Image 2: Photograph by King’s Studio, image courtesy of University of Birmingham and HPC (HPC ref: Mx04-103)