Sustainability of Oyster fishery in Ireland

- Sustainability rating: wild - 4 (try to avoid)

Farmed native, rock and Pacific - 1 (eat more) - Recommended minimum size: wild native 76-78mm; farmed size dependent

- Season: wild and farmed natives – avoid May – August (spawning); Farmed gigas no seasons

- Main Irish fishing method: if not harvested on farms, harvested by dredging

Oyster farming impact

The farming of oysters and other shellfish is as sustainable as it gets and in many places actually restorative environmentally. It holds great promise for relieving pressure on land-based protein sources and is a great example for how to gain more food from the ocean. Restoration of oyster populations are encouraged for the ecosystem services they provide (as described in the ecology of the Irish oyster).

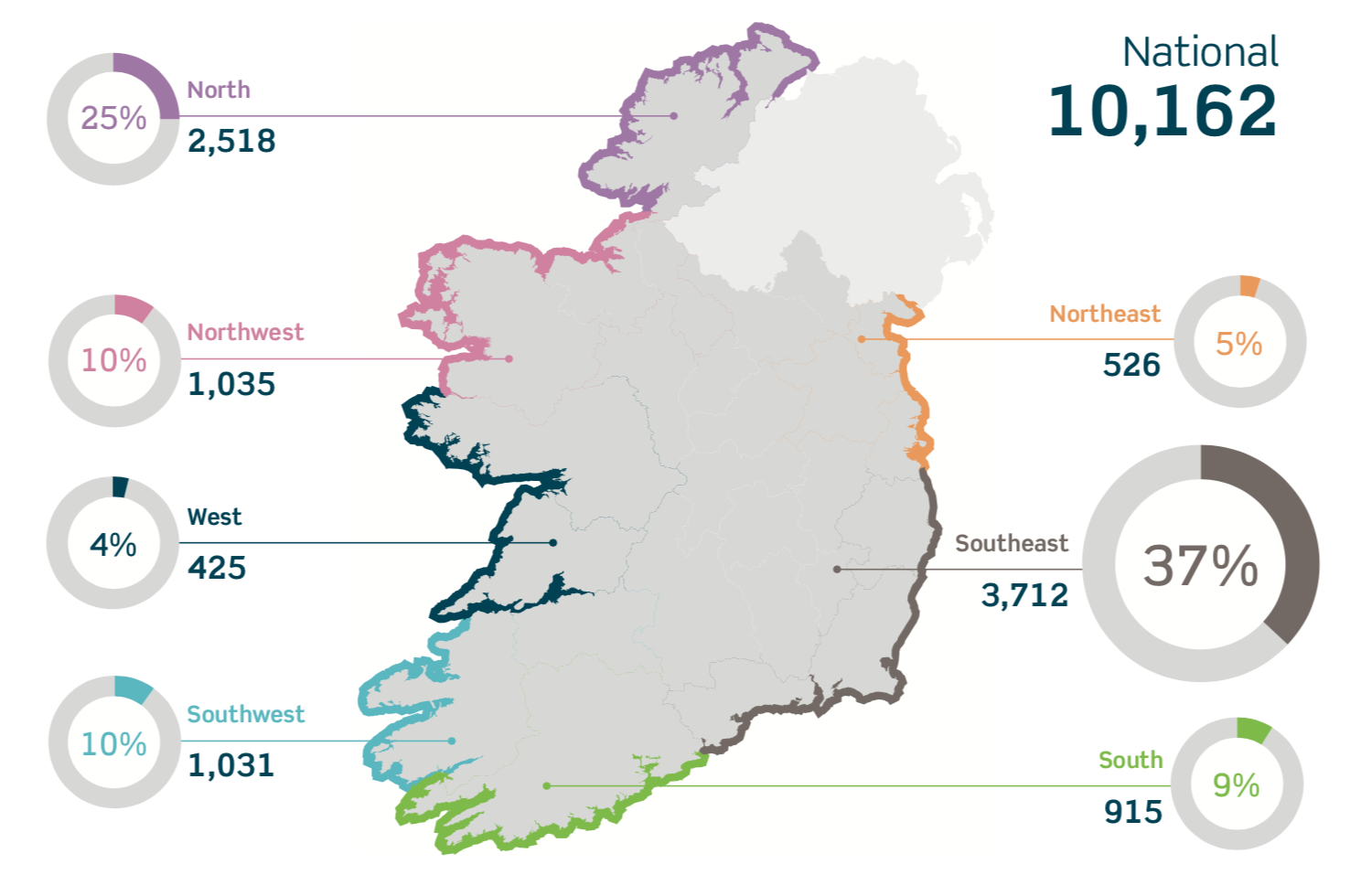

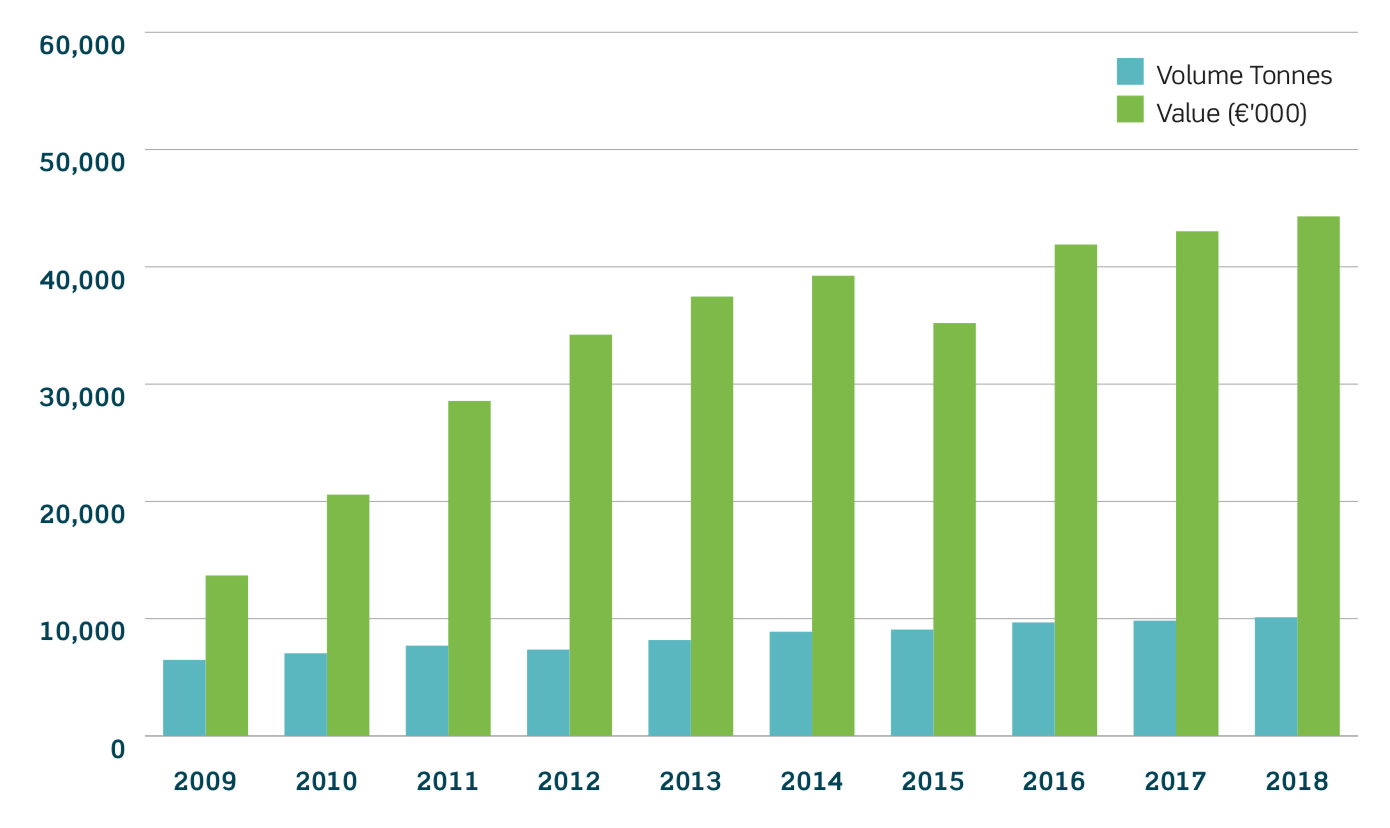

As mentioned on our history page, in Ireland there are currently around 130 oyster farms nationwide having producing 10,300 tonnes of oysters worth over €44 million in 2019 with Co. Donegal and Waterford accounting for about 60% of the Irish production. The two main oyster species that are farmed are Ostrea edulis (the European flat or native oyster) and Magallana gigas, the introduced Pacific oyster.

Generally there are about five steps involved in oyster farming. The first few steps are carried out in a controlled tank environment, i.e. water composition, temperature, food and light are all controlled and nothing is left to chance.

First of all a solid and high qualitative broodstock is key to successful oyster farming. These oysters are the “parents” or base of an oyster farm that provide the gametes. It is important to have a large number of oysters, because it is impossible to tell if an oyster is male or female from its outer appearance.

In the hatchery, fertilisation of eggs with sperm takes place within minutes and cell division occurs over the next 24 hours. There can be as many as 110 million fertilised eggs in 7,000 litre tanks in the rearing rooms depending on each farm’s capacity.

As soon as the eggs are fertilised, the beginning-stage larvae are fed with cultures of phytoplankton (algae) on a daily basis. Here it is important that the water is clean and changed regularly to ensure no pathogens or foreign organisms enter the system and compete with or eat the larvae. This is the most fragile stage of an oyster's life history. In two to three weeks, the larvae develop an eye-spot and a foot, a sign that they are ready to latch on to a hard substance.

When this happens, the oyster larvae are ready to move into nurseries which are usually outdoor systems in ambient water with a variety of cultch options. The best cultch is usually full or ground up oyster shells because oysters are naturally attracted to other oyster shell to ensure their future reproductive success. After the larvae settle, they are considered ‘spat’.

The loose spat may be allowed to mature further to form ‘seed’ oysters with small shells. In either case (spat or seed stage), they are set out to mature after approximately six months.

The maturation technique is where the cultivation method choice is made and where the oyster’s unique taste, quality and appearance is formed.

In  one method the spat or seed oysters are distributed over existing oyster beds and left to mature naturally. Such oysters will then be collected or harvested using the same fishing methods that are used for wild oyster harvesting, most commonly dredging.

one method the spat or seed oysters are distributed over existing oyster beds and left to mature naturally. Such oysters will then be collected or harvested using the same fishing methods that are used for wild oyster harvesting, most commonly dredging.

In the second method the spat or seed may be put in racks, bags, baskets or cages (or they may be glued in threes to vertical ropes) which are held above the bottom. Oysters cultivated this way are harvested by lifting the bags or racks to the surface and removing mature oysters, or simply retrieving the larger oysters when the enclosure is exposed at low tide. The latter method avoids losses to some predators, but it is more expensive.

In the third method the spat or seed are placed in a cultch within an artificial maturation tank. The maturation tank is fed with water that has been especially prepared for the purpose of accelerating the growth rate of the oysters. In particular the temperature and salinity of the water are altered somewhat from nearby sea water. The carbonate minerals calcite and aragonite in the water help oysters develop their shells faster. This cultivation technique is the least susceptible to predators and poaching, but is the most expensive and labour intense to build, manage and operate. The Pacific oyster is the species most commonly used with this type of farming.

The oysters remain in their grow-out environment until they are harvested after about 3-4 years.

Most Irish oyster farmers use methods one and two, utilising the many sheltered bays along the west coast with the unspoiled Atlantic water to their advantage.

Before the mature oysters go to market, they are graded. In Ireland and the UK, this is done by size while France grades them purely by weight. The following applies when you buy oysters in Ireland: grade 1 is the biggest and grade 4 is the smallest while it is said that a size of grade 2 is the best value for money for your oyster.

Economic importance

The Farmed Pacific or Gigas oyster sector continued to expand modestly by 2.4% in volume in 2018, breaking the 10,000-tonne ceiling to 10,122 tonnes. The overall value of oysters increased by 2.3% to €44.3 million, the unit value nationally remained unchanged at €4,380 per tonne BIM aquaculture report 2019.

In 2018, the value of Irish oyster sales to China increased by 83% compared to 2017. This made China Ireland’s second largest market for Irish oyster export. France was the only export market for a long time, but a few years ago branding was facilitated which opened up new markets and home-branded products are increasingly being sold directly to the retail market.

The Irish oysters are seen as a premium and pure product that comes from clean waters surrounding a green island and especially the Chinese, world’s biggest oyster growers appreciate this on the international market.

Management of the native oyster

Management authority has been devolved to local co-operatives through fishery orders issued in the late 1950s and early 1960s or through 10 year Aquaculture licences. In Lough Swilly and the public bed in inner Galway Bay management authority rests with the overseeing government department rather than with local co-operatives. Operators require a dredge licence which is issued by Inland Fisheries Ireland (IFI).The oyster co-operatives operate seasonal fisheries and may also limit the total catch. Minimum landing size for wild and oysters that are farmed by the naturally maturing method is 76-78mm.

Many oyster farms aquire certificates such as 'Origin Green Ireland' and 'EcoPact' which assure responsibly sourced seafood.

Origin Green Ireland is an initiative by Bord Bia and Ireland’s pioneering food and drink sustainability programme, operating on a national scale, uniting government, the private sector and the full supply chain from farmers to food producers and right through to the foodservice and retail sectors.

The programme is the worlds’ only national food and drink sustainability programme, and enables the industry to set and achieve measurable sustainability targets that respect the environment and serve local communities more effectively.

The programme is the worlds’ only national food and drink sustainability programme, and enables the industry to set and achieve measurable sustainability targets that respect the environment and serve local communities more effectively.

BIM brought in the initiative 'EcoPact' in which they assist farmers to draw up an Environmental Management Programme based on agreed targets to improve their farm’s environmental performance. This includes the examination of every environmental aspect of the operation, such as waste management, nature conservation, visual impact and the use of public piers.

Current threats

While climate warming has taken the sting out of harsh winters, oyster farms have regulated exploitation and disease control has massively improved, the biggest threat to our oysters nowadays are parasites. Slipper limpets, starfish and dog whelk continue to take their toll on native and farmed stocks without ever reaching plague proportions. However, two relatively recent invaders, the stink winkle and the American oyster drill, are becoming more worrying. They drill holes in the oysters and suck out their flesh. The long-term consequences of these parasites are still mostly unclear.

Stock structure

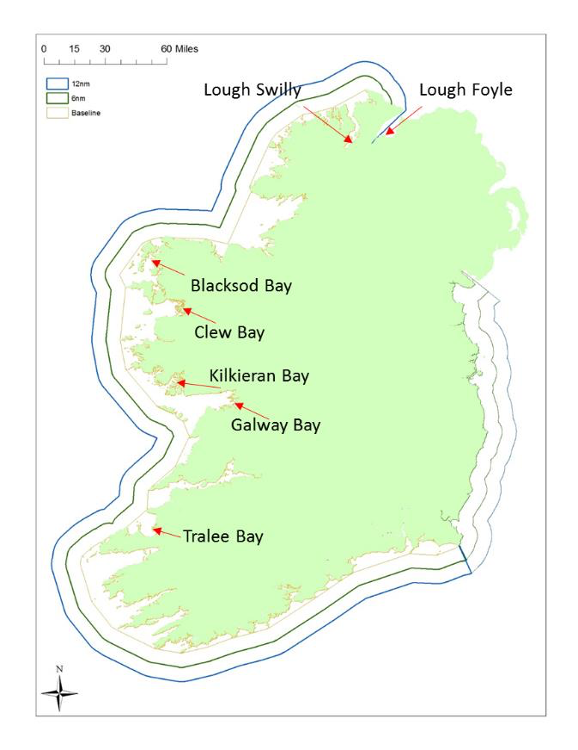

Native oyster stocks nowadays occur as discrete isolated units in a number of Bays around the coast. Although once widespread in many areas, including offshore sand banks in the Irish Sea and along the south east coast their distribution is now drastically reduced. The main stocks occur in Tralee Bay, Galway Bay, Kilkieran Bay, Clew Bay, Blacksod Bay, Lough Swilly and Lough Foyle.

The image shows the operation of an oyster farm on the Irish coast. No fishing vessels are necessary, however, manual labour is intense as the oyster bags have to be turns and checked frequently.

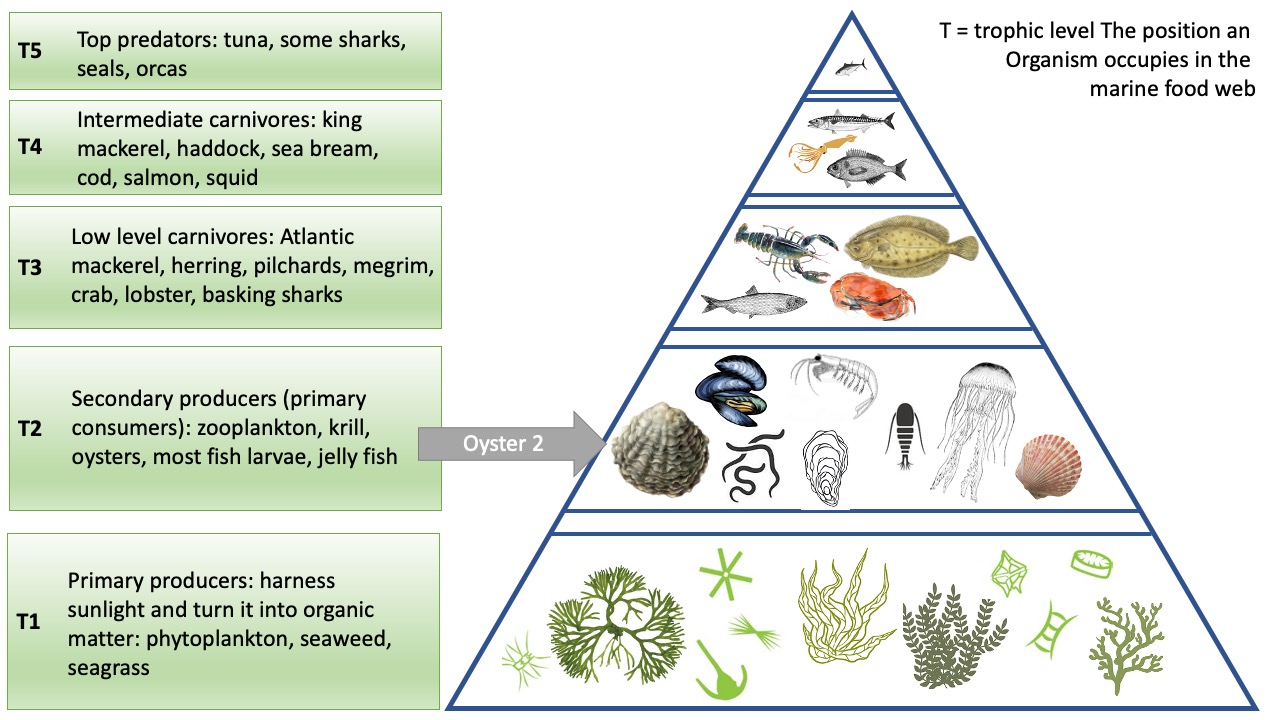

Oysters in the Marine Food Pyramid