History of the Irish oyster

There are three types of oysters that are cultivated and eaten in Ireland: the native or European flat oyster (Ostrea edulis), the Portuguese rock oysters (Crassostrea angulata) and the Pacific oyster (Magallana gigas or Crassostrea gigas). The Portuguese oyster was introduced in the 19th century, but is not commercially grown in Ireland anymore.

There are three types of oysters that are cultivated and eaten in Ireland: the native or European flat oyster (Ostrea edulis), the Portuguese rock oysters (Crassostrea angulata) and the Pacific oyster (Magallana gigas or Crassostrea gigas). The Portuguese oyster was introduced in the 19th century, but is not commercially grown in Ireland anymore.

All the names attached to the different oyster species can sometimes get a bit confusing, but rest assured the only two names that you need to remember are: Irish rock oyster (Magallana gigas) and native flat oyster (Ostrea edulis) which are the two oysters that are now grown in Ireland. The Irish name for oyster is ‘oisre’.

Ireland is the perfect location for oyster farming with over 7,000km of a very indented coastline to work with and rain filtering through 12,000km2 of turf land. Oyster cultivation in Ireland dates back to the 13th century but consumption of oysters in Ireland has been a tradition for over 4,000 years.

The native oyster (Ostrea edulis) is of great cultural value in Ireland, its fishing and cultivation have formed the heart of coastal communities for centuries and can be traced back to Roman-times.

The bivalve’s importance as a key food item in Irish cuisine is evident nationwide. Archaeological findings show extensive oyster consumption from the late Mesolithic period in shell middens all around the coast. Particularly, oyster middens seem to have dominated some early Bronze Age sites. Large quantities of the mollusc were hand-picked along the shore and eaten by coastal populations. Experts say that there were naturally occurring oyster stocks in almost all suitable bays around Ireland. The native oyster seemed to have been so plentiful along the Irish shoreline that the exploitation and consumption by coastal communities living in these prehistoric times had little effect on the stock.

Compared to those times, written reports from as early as 1461 (the so-called “Chain book” of the city of Dublin) illustrate the growing economic importance of the oyster business through regulations on the oyster fishery for Dublin’s fish market.

Reports from the late 17th century give detailed account on the abundance and size of the native Irish oyster as well as the increasing consumption of the bivalve, especially among city dwellers. In fact, oysters became so popular with increasing commercial importance that artificial oyster beds were located north of Dublin City in Clontarf and Howth (Sutton) to ensure a steady supply.

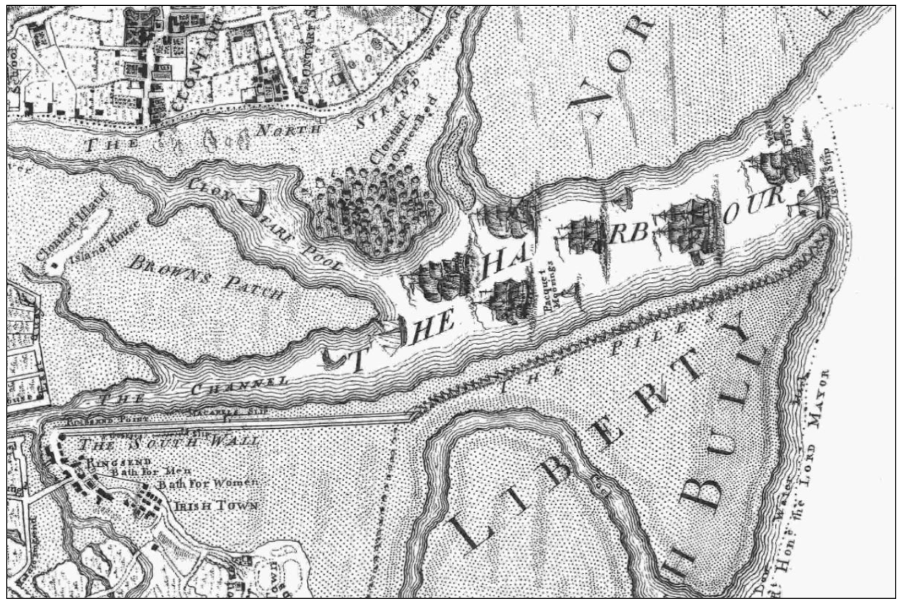

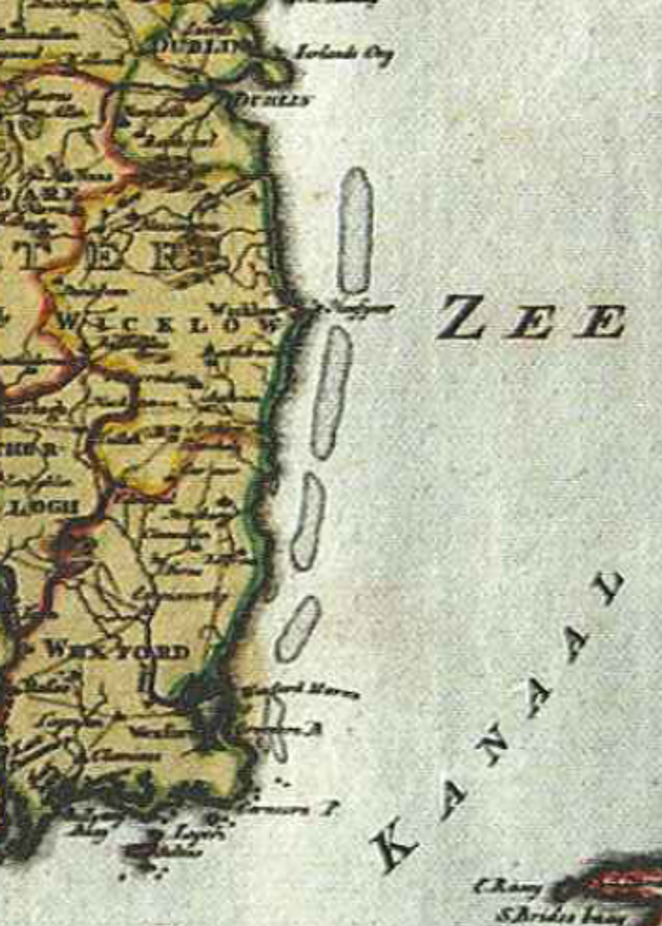

Figure1 shows a map of Dublin Bay with the artificial oyster beds in Clontarf in 1760 by Rocque. These artificial beds were replenished from the naturally occurring beds from Arklow and Glascurrig, Co. Wexford as well as from Carlingford, Co. Down. These natural beds didn’t just provide oysters for many artificial Irish beds, but also for others in Britain, Jersey, Holland and France. Figure 2 shows the natural oyster beds along the Wexford coast mapped by Tirion (Amsterdam) in 1754.

John Rutty (1697 - 1775), a Dublin Quaker physician and naturalist writes in his book ‘The natural history of the County of Dublin’ published in 1777 that he observed natural oyster beds in Dublin Bay along with the artificial ones. According to Rutty these were found in Poolbeg and they even produced pearls until navigation took priority over fishing and the well-known Poolbeg oysters were wiped out.

Rutty also reported about an oyster bed in Malahide, that was ‘supplied by nature and does not require to be renewed as the artificial [one]’. Rutty was talking about the partly green-finned oyster which was praised to be the most delicious of all oysters. The Malahide oyster bed was deemed an ancient bed, extending over an area of approximately two acres with great numbers of the large native European flat or green finned oysters which were harvested annually, except during the breeding season from 15 May to 4 August. The level of the water at low tide made this a relatively easy task. The bed was located in the Malahide estuary where the railway viaduct is now.

Along with all the fishing rights in the estuary, the oyster fishery was the property of the Manor of Malahide who leased the beds and maintenance to capable lessees.The rental from leasing the bed was an important source of income and food to the Malahide Estate. A number of these leases survive among the Talbot Estate papers including an indenture dated 1 May 1835 whereby Richard Talbot let to Henry Murphy and John Gaffney & son, the oyster beds for a yearly rent of £110-15 -4½ and ‘five thousand marketable oysters to be delivered in such quantities and at such times as he may demand or require at the oyster beds under penalty of Fifty pounds in any year that the same shall not be supplied’.

The building of the railway in the mid 19th century seemed to have had a dramatic effect on the Malahide oysters. In 1864, John Gaffney stated that the railway caused considerable injury to the beds due to the accumulation of mud as well as by cutting off nearly ten acres of the original beds.

While natural oyster beds elsewhere also declined due to harsh winters, over-harvesting and pollution of inshore waters, the way oysters were consumed changed as well. For over two centuries they were either preserved or cooked as a bulker of other ingredients in stews and pies or baked into loaves of bread which our historical recipe shows. As they became scarcer, they began to be treated with greater respect and became the first real ‘fast food’ for the masses of the industrial revolution with oyster vendors becoming a common sight in the picture of towns and cities selling raw oysters.

The artificial beds in Clontarf and Sutton flourished for a long time and provided oysters for the masses for years.

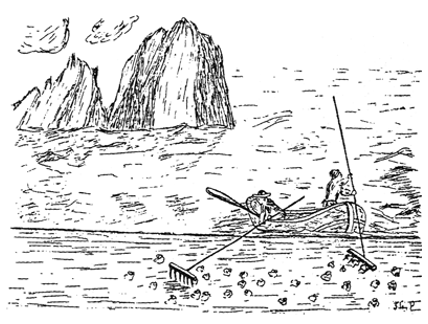

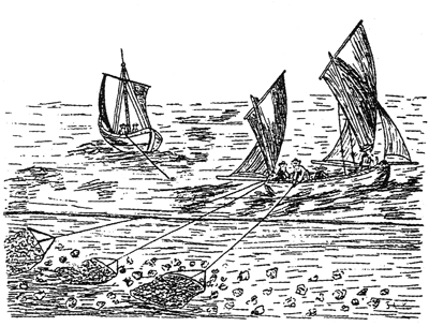

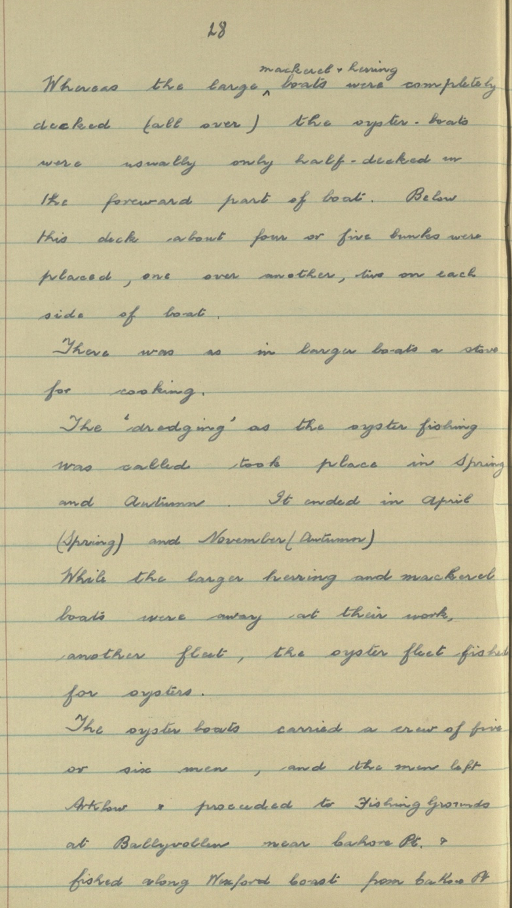

The oyster fishery was a lucrative if labour intense business as the following example by The National Folklore Collection shows Dúchas.ie. It gives a detailed inside into oyster fishing along the Irish south-east coast: The Schools’ Collection, vol. 0924, p. 28 © National Folklore Collection, UCD

- "Whereas the large mackerel & herring boats were completely decked (all over) the oyster-boats were usually only half-decked in the foreward part of boat. Below this deck bout four of five bunks were placed, one over another, two on each side of boat.

- There was as in larger boats a stove for cooking.

- The 'dredging' as the oyster fishing was called took place in Spring and Autumn. It ended in April (Spring) and November (Autumn).

- While the larger herring and mackerel boats were away at their work, another fleet, the oyster fleet fished for oysters.

- The oyster boats carried a crew of five or six men, and the men left Arklow & proceeded to Fishing Grounds at Ballyvollen near Cahore Pt. & fished along Wexford Coast from Cahore Pt."

With improved facilities of transport, the oyster stock became exploited for non-coastal communities which was the beginning of the end for the oysters. Continued overharvesting of the shellfish in the 19th century along with heavy pollution, harsh winters and the disease Bonamia ostrea led to a dramatic decline of the native oyster in Ireland and threatened to wipe out its stock altogether. Projects such as the Ardfry Experimental Oyster Cultivation Station in Co. Galway in 1903 to safe the species failed in the attempt to cultivate it and times were dire for the native oyster.

Attempts to acclimatize the Portuguese rock oyster (Crassostrea angulata) in the late 19th century were partly successful in that they helped replenish Ireland’s native overfished stocks to an extend as a faster growing more resistant species. However, they weren’t able to naturally spawn in our cold waters and cultivation methods failed when the iridoviral disease decimated the species in 1969. The Pacific oyster Magallana gigas also known as Crassostrea gigas and nowadays referred to the Irish rock oyster, was introduced to Irish coastal waters in the early 1970s to remedy the decline in oyster production. This species seemed to be easier and faster to cultivate and it delivered more meat content than the native oyster. The other great advantage of this species was that it deemed to be resistant to almost any nasty disease. And while the native Oyster (Ostrea edulis) is seasonal, as it spawns during the summer months hence only available when there's an ‘R’ in the month, the Pacific oyster doesn't spawn in the cold waters around Ireland so is available all year round.

Commercial oyster farming with the introduced Magallana gigas seriously kicked off in the 1980s and 90s. While the Portuguese rock oyster has not been cultivated on a commercial level since the 1970s.

Nowadays, there are close to 130 oyster farms nationwide producing around 10,000 tonnes of oysters annually with Co. Donegal and Waterford accounting for about 60% of the Irish production.

Oysters from Ireland are rich and varied in taste with each bay, in which they are grown, contributing to this distinctive flavour. The unique blend of wild Atlantic waters, clean freshwater rivers and minerals from an unspoilt landscape makes each Irish oyster a unique taste experience. Due to abundant plankton and the exceptional growing conditions around the Irish coast, oysters from Ireland have distinctively high meat content.

In recent years a lot of branding of the ‘Irish Oyster’ is happening since a premium is paid for them, especially on the Asian market. The ‘Irish Rock Oyster’ is in fact the Pacific oyster (M. gigas) introduced to Irish waters in the early 1970s from the Pacific side of Asia. It might not be as high a quality as the native oyster Ostrea edulis, but it is seen as superior in quality and taste to other cultivated oysters elsewhere in Europe.

Throughout history, the Irish oyster enjoyed a unique reputation for its high quality standard. Many wealthy Dubliners praised specifically the Malahide oysters, exemplified by Dr. G.A. Little, who decamped with his family from Rathgar to ‘Ormiston’ on Church Road each August in the early part of the last century. He quotes a fish seller’s cry in his essay “About Malahide”:

- Oysters, oysters, Sir, said she,

- If you want oysters buy them from me;

- Two for a penny, but three I'll give thee

- If you’ll buy my Malahide oysters.

- Oysters, oysters fresh and good,

- As ever came from an ocean flood,

- They'll nourish your heart, cherish your blood.

- Come buy my Malahide oysters.

Ecology of the native oyster

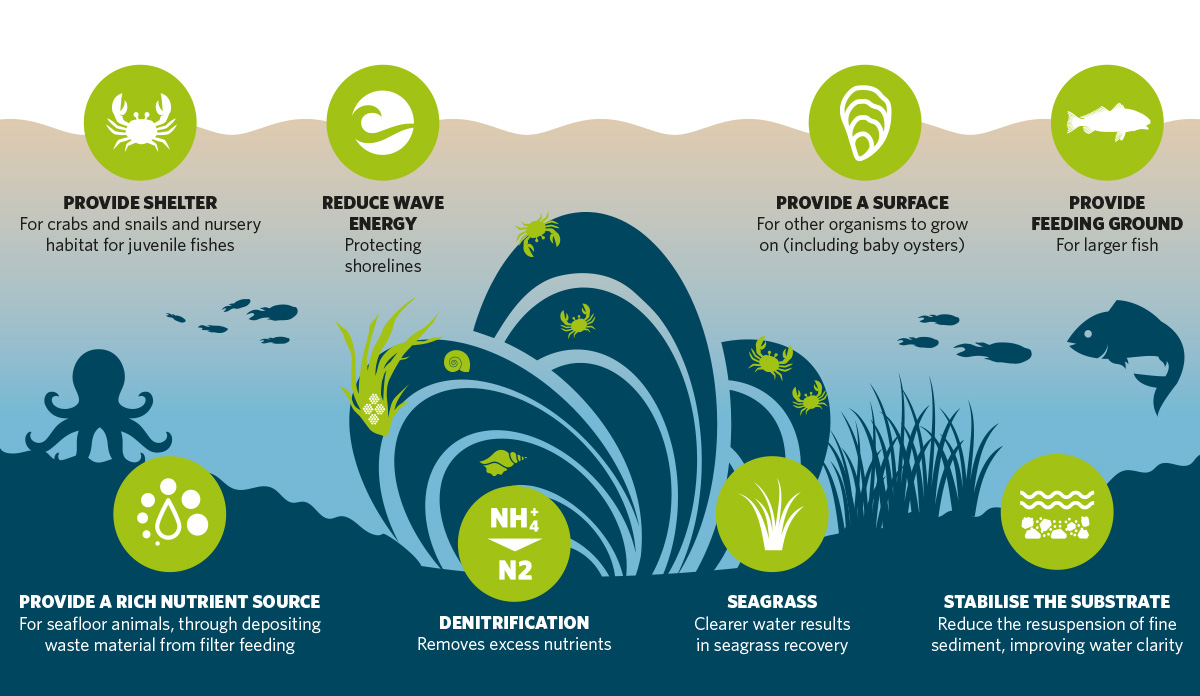

Almost all oyster species are habitat-building bivalve molluscs. Young oysters are so small that they are part of the zooplankton community for a while, free-floating in the water column, before they preferentially settle out on adult oysters or any suitable hard substrate. Once settled, oysters fuse their shells to the underlying substrate and can therefore form dense aggregations, known as an oyster reef.

Oyster reefs provide us with a range of ecosystem services and hold both economic and environmental importance. The complex reef structure provides food and habitat for numerous marine creatures and may serve as nursery grounds for some fish species.

Oysters are filter feeders which means they filter water for nutrients and particles to feed on and grow. They are true eco-engineers as a single oyster is able to filter up to 240 litres of seawater per day. Their filtering activity improves water quality on local scales, because they remove particles from the water and deposit them on the sediment, where conditions for bacteria that break down pollutants such as nitrates are better. This results in enhanced rates of denitrification, a process in which nitrites and nitrates are transformed into inert di-nitrogen gas. This is a very important chemical process as high levels of nitrogen can be detrimental to the environment consequently leading to harmful algal blooms, depleted oxygen and fish death. By removing particles from the water column oysters can also increase light penetration to the sediment, and promote the recovery of seagrasses, another threatened and valuable coastal habitat.

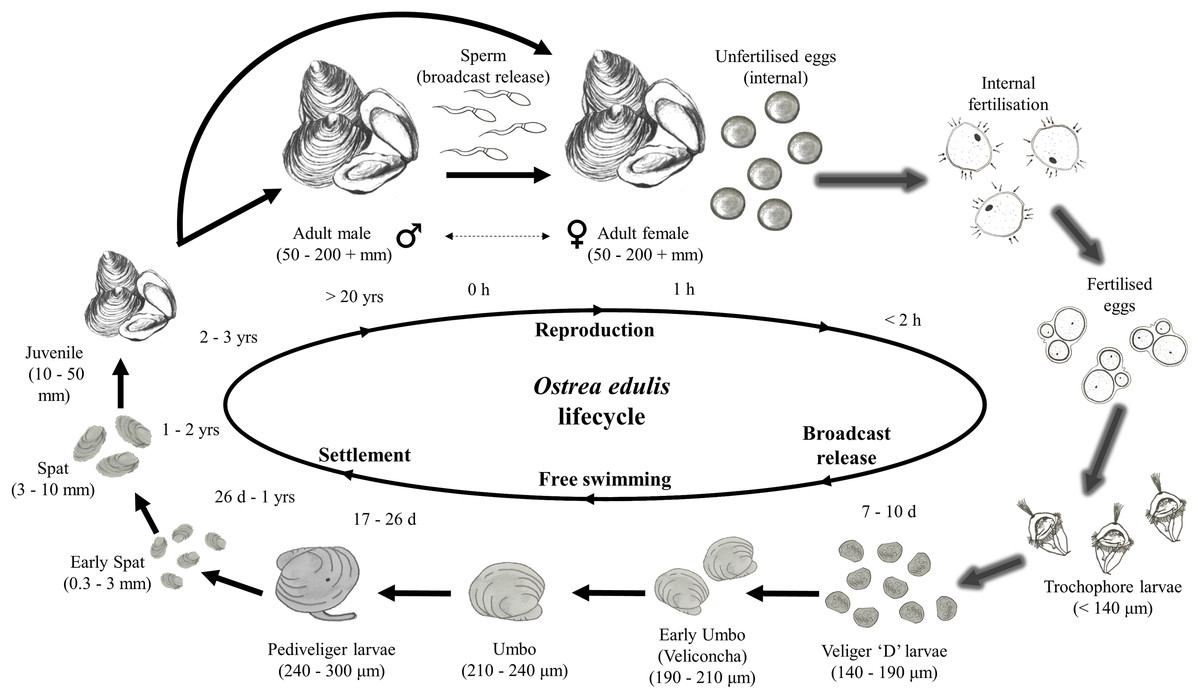

The native oyster on which we focus here grows up to approx. 15cm with an age of up to 30 years while sexual maturity is reached at an age between 3-4 years.

It’s shaped round rather than oval and is relatively flat, therefore it is often referred to as ‘flat oyster’. It is easy to distinguish it from the Pacific oyster which grows bigger, deeper and is oval-shaped with spectacular ridges.

The natural habitat of O. edulis are estuaries and sea lochs as well as open coastal seas as deep as 50m depth. This species is primarily found in the subtidal zone and colonises on mixed hard substrates, in particular shell material. The range of the native oyster is pan-European which includes the northeast Atlantic from the south of Norway to the Mediterranean Sea as far as the Black Sea.

The native oyster is the only species that spawns in our temperate waters which usually happens in our summer months or for easier memory in the months without an ‘r’ (May - August). During the spawning process, the oyster’s body goes from being opaque to translucent, almost watery in appearance. During this time avoid eating native oysters as they will taste very unpleasant, highly acidic and thin.

Since the Irish rock oysters or Gigas don’t spawn in our waters (they spawn in temperature controlled tanks in commercial hatcheries and nurseries) they can be enjoyed all year round.

Once the egg of an oyster is fertilized, it begins to divide. It becomes a trochophore, with hair-like structures called cilia, to help it move in the water column and search for food. In the veliger stage, two shells develop and an organ called the velum forms, allowing for feeding and additional movement – at this point the oyster is D-shaped.

In its free swimming larval stage, the oyster develops a foot and an eye and is called a pediveliger. This is the time when it needs to look for a surface to attach to. Oysters in the wild will attach to any hard substrate, including rocks, driftwood and piers, but the ideal substrate is another oyster as this indicates that there’s enough algae and water circulation to support an oyster to adulthood. Thus, oysters often settle on top of each other to form complex oyster reefs. The unique 3-dimensional habitats created by native oysters support a higher biodiversity of species than the surrounding sediment/seabed. By providing a structure the reef is colonised by algae, tunicates, sponges, crabs, crustaceans and ascidians which all leads to increased biodiversity and fish abundance as the growing reef provides a protected nursery ground for juvenile fish, refuge from predation and a source of food.

Once the oyster sets on a substrate, it is called ‘spat’ and the process is called ‘spat fall’. Later on, it becomes a juvenile oyster, and continues to grow and remains in this stage until adulthood, when it is able to reproduce. This is of course it’s natural path. Oyster cultivation and farming works a bit differently which we will explain in brief on our oyster sustainability page).

Oysters are hermaphrodites which means they are born with a particular sex, but can switch between being male and female. Researchers found that they do this sex-change several times during their lifespan.

Health benefits

Oysters are packed with minerals and vitamins and an excellent source of zinc, calcium and selenium as well as vitamin A and B12. They make a very healthy food choice, because they are low in calories and rich in protein.

Traditionally, oysters are considered to be an aphrodisiac, partly because they resemble female genitals. Researchers have also found that they are rich in amino acids that trigger increased levels of sex hormones (in males and females) and their high zinc content aids the production of testosterone.

Oyster protection and restoration

Threatened and/or Declining Species and Habitats for the North-East Atlantic, the native European oyster is further included in NORA Ramsar as “shellfish reefs” and by some member states as “Reef” in the Habitat Directive.

Recently many oyster restoration projects have shot out of the ground across the globe. Europe shows incredible consorted efforts in restoring the native European oyster Ostrea edulis best represented through NORA (Native Oyster Restoration Alliance) since 2017.

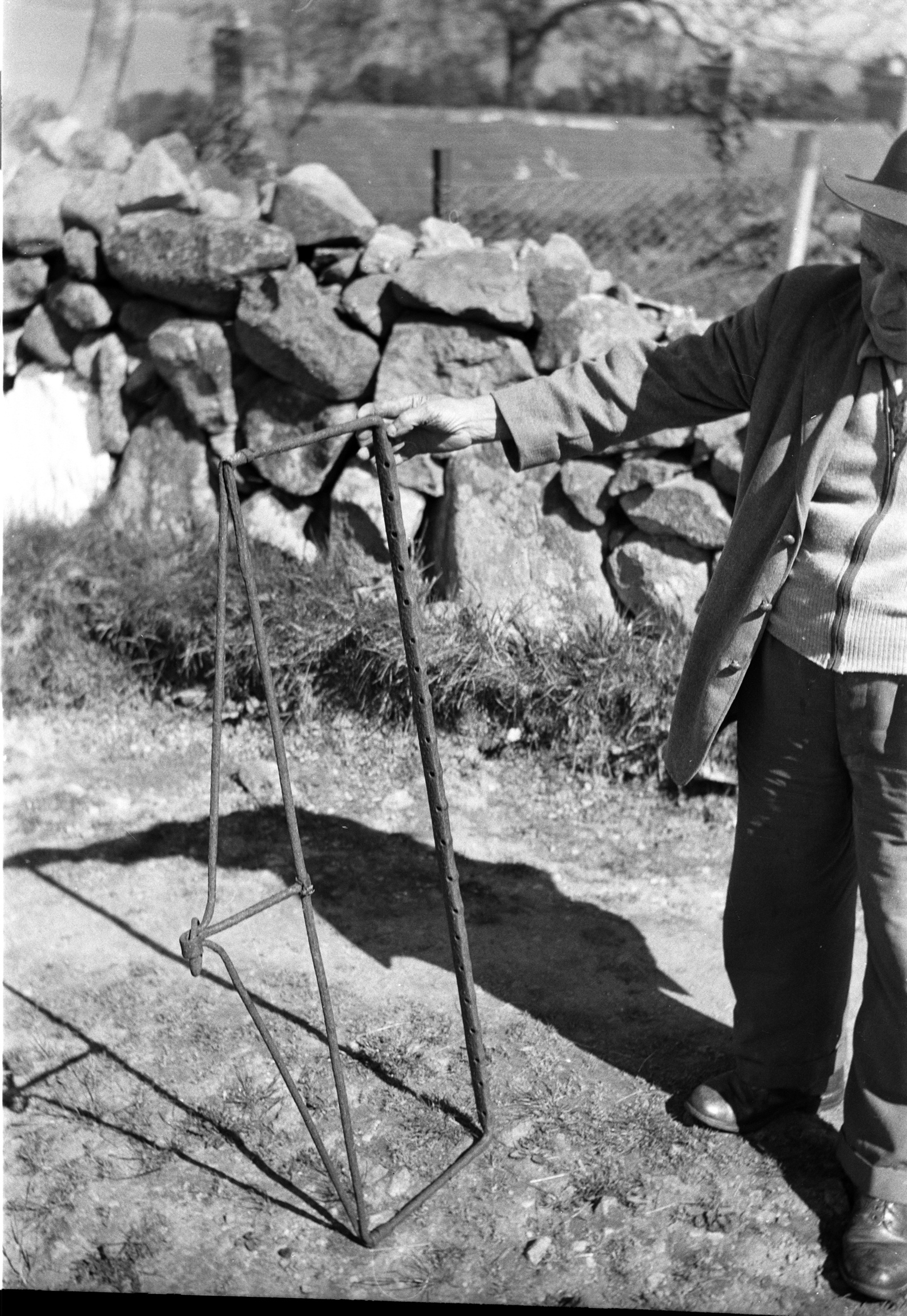

In Ireland great work on restoring the native oyster is on-going by the Marine Institute and Cuan Beo within the Native Oyster Network UK & Ireland. The project's aim is to find suitable areas for the restoration of the native O. edulis. For that assessment of the current distribution and abundance of oysters in the Bay is performed through a combination of intertidal transect and sub-tidal dredge surveys using a broad participation of native oyster fishermen and oyster growers. A model that characterises the Bay in combination with new experimental data on the response of oyster to low salinities over a range of temperatures will be used to develop a map of suitable oyster habitat. Cultch (settlement substrate) is deployed at a number of sentinel sites to monitor the distribution of spat fall and to evaluate the efficacy of different types of cultch in attracting spat. These data are collectively used to inform larger scale cultch trials in 2019 and 2020. In parallel disease monitoring, particularly for Bonamia which has been present in the Bay for a number of decades, has been enhanced. The oyster beds are within a Special Area of Conservation.