History of Scallops around Ireland

The Great scallop (Pecten maximus) or King scallop also called Pilgrim scallop and in Irish 'Muirín' has a special religious significance. The shell has for many centuries been the badge worn by pilgrims to the shrine of St James at Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, Spain. This was in honour of Saint James and gave rise to the alternative name. When the shell is displayed with its convex outer surface showing it is usually referring to this Christian ritual. However, when the shell refers to the goddess Venus it is displayed with its concave interior surface showing connected to femininity and the symbol of birth and fertility.

The Great scallop (Pecten maximus) or King scallop also called Pilgrim scallop and in Irish 'Muirín' has a special religious significance. The shell has for many centuries been the badge worn by pilgrims to the shrine of St James at Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, Spain. This was in honour of Saint James and gave rise to the alternative name. When the shell is displayed with its convex outer surface showing it is usually referring to this Christian ritual. However, when the shell refers to the goddess Venus it is displayed with its concave interior surface showing connected to femininity and the symbol of birth and fertility.

The earliest known records of true scallops can be found from over 200 million years ago (from the Triassic period). Fossil records also indicate that the abundance of species within the Pectinidae has varied greatly over time. Nearly 7,000 species and subspecies names have been introduced for both fossil and recent Pectinidae.

The family name Pectinidae, which is based on the name of the type genus, Pecten, comes from the Latin word ‘Pecten’ meaning comb, in reference to a comb-like structure of the shell situated next to the byssal notch. The Irish name “Muirín” means as much as “born of the sea” and Irish legend has it that this was the name of a woman who was transformed into a mermaid. After 300 years, she was brought to shore, baptized and transformed back into a woman.

Most historical references to scallops in Ireland refer to the king scallop Pecten maximus, although the much smaller Aequipecten opercularis or queen scallop also referred to as “Queenie”, in Irish 'Cloisin' would have also had a place in Ireland’s coastal cultural heritage.

According to John Rutty (1772), P. maximus was abundant in Dublin Bay and in season from March through to May. It was by some preferred to the oyster as a sweeter and more nourishing food and the shells were used as vessels in dining. Rutty reports that the great frost in 1739-40 killed many of them on our coasts.

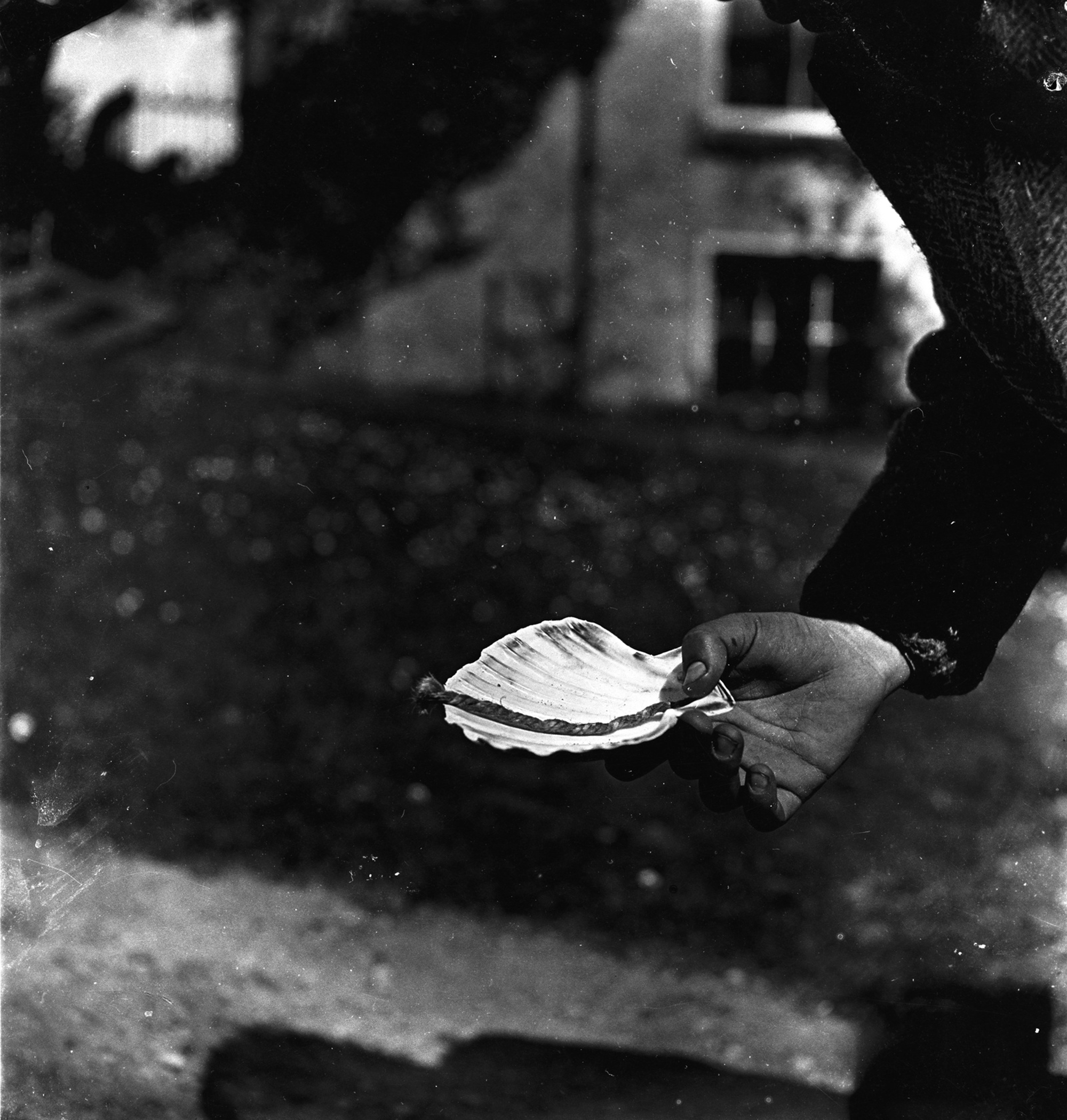

Scallop shells were not only used as dining vessel to contain sauces in wealthy Irish homes, but also as lights as can be learned from a story in the Duchas archives (The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0786, Page 79): Told by Mrs Nicel (76) Loughshinny, Skerries. She heard it from her mother.

- “Many years ago the people had no lamps or paraffin oil to burn in them. They had to get oil from the dogfish by getting the liver and boiling it down until it was oil. This oil they put into very deep shells such as the shell of the scallop. Then they had to get wicks to burn in the oil. They made wicks by plaiting cotton threads together. They cut them short and put them into the oil and lit them. They made a fine light and burnt brightly.”

A wise Irish saying goes like this: "The day of the wind is not the day of the scallop."

Ecology of Scallops

Two commercially important species occur on our Irish coasts: The queen scallop (Aequipecten opercularis) and the king scallop (Pecten maximus) both home the northeast Atlantic along the European coast from northern Norway to the south of the Iberian peninsula. The king scallop has also been reported off the Macaronesia Islands.

The main differences of these two species is the size and shape. While king scallops has one convex shell and one that is flat (acting as a lid), both shells of the queen scallop are convex. Another difference is the size, where ‘Queenies’ are about half the size of a king scallop and often sold without the roe or ‘coral’ attached (the orange bit). Both bivalves have a sweet, delicate flavour with a meaty texture and require very little cooking.

The edible part of the scallop is the adductor muscle, used to open and close the scallop’s shells, enabling it to propel itself by expelling water. You often see this pale bit of meat sold together with the orange roe or ‘coral’ attached.

The bivalve lives buried in the surface layer of soft sea-beds, such as sand, mud and gravel, and filter feeds on plankton and detritus. For this the shell opens up to two centimetres and the mantle, with thousands of tentacles, becomes visible. The scallop has a ring of eyes all around the mantle to improve sensory ability and detect predators such as starfish.

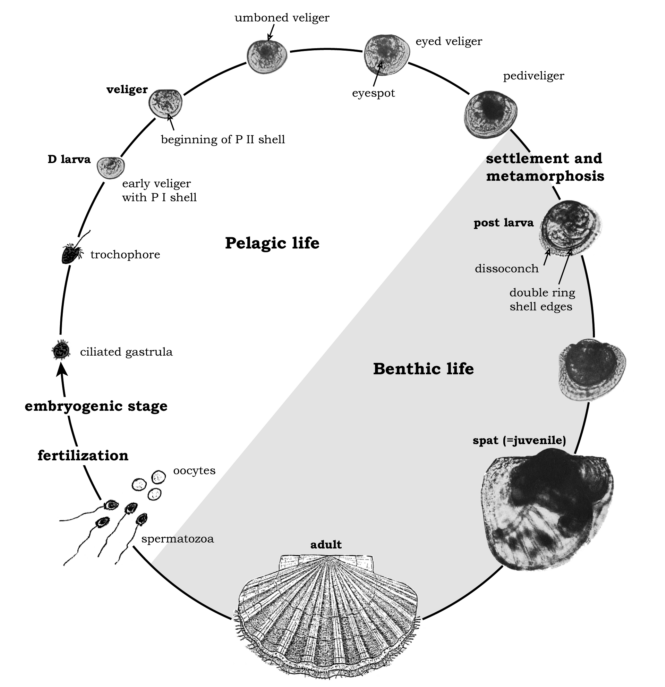

King scallops are hermaphrodites meaning they have both reproductive organs (like most scallop species) and spawn twice a year. They reach maturity at the age of three, when they measure approx. 9cm in diameter. Spawning takes place in the warmer months, from May to August, and a three-year-old individual can produce between 15 and 21 million eggs each year. Older adults seem to be able to spawn twice a year with partial spawning in the Spring and full spawning in late August.

After spawning the animals undergo a period of recovery of the gonad before they spawn again. Fertilization of the gametes is external and either sperm or oocytes can be released into the water column first.

The larval stage of Pecten maximus is relatively long, up to a month and the potential for dispersal is quite high. Once an egg is fertilized, it becomes part of the plankton community drifting in the water column for four to seven weeks before settling to the ocean floor, where they attach themselves to objects through their byssal threads. The byssus is eventually lost with adulthood and the scallop transforms into a free swimmer. Rapid growth occurs within the first several years, with an increase of 50 to 80% in shell height and quadrupled size in meat weight. The commercial size is usually reached when the scallop is five years old. However, some scallops have been known to live more than 20 years with a shell diameter of more than 20cm.

Scallops in shallow water grow faster than those in deeper water; the growth halts in winter and starts again in spring, producing concentric growth rings much like tree rings.

Scientists use these growth rings of fossil shells of P. maximus as a high‐frequency archive of paleoenvironmental changes since the molluscs’ growth is influenced by its environment and therefore indicative of the prevalent climatic oean conditions.