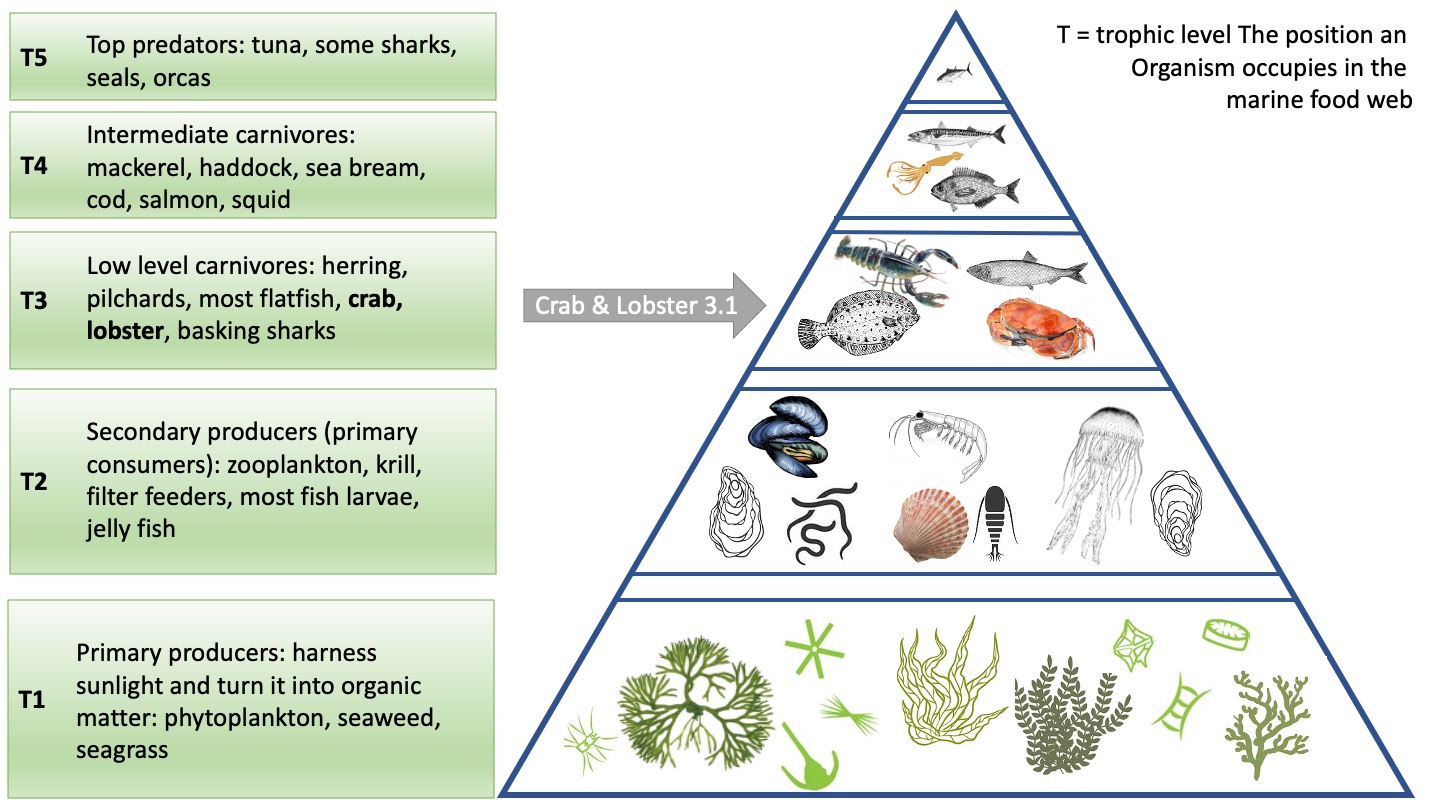

Sustainability of lobster fishery in Ireland

Lobster fishing is currently sustainable in Ireland. The biggest impact on the environment with this fishing method is the fuel and energy consumption by the small scale fishing boats.

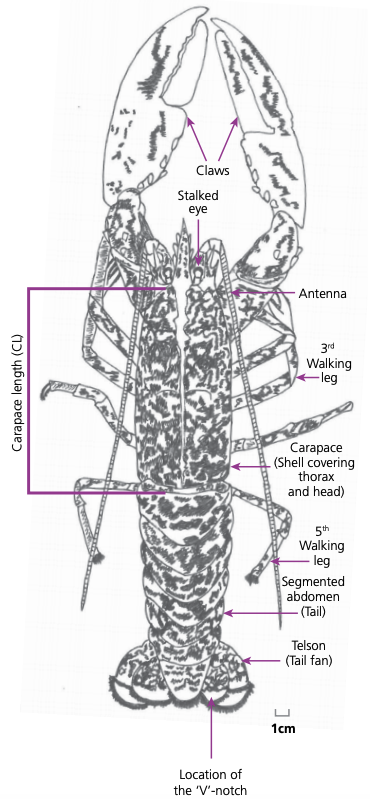

In 1994 a scheme was started in Galway Bay to mark the tails of young female lobsters carrying eggs with a v-notch. They were thrown back o sea so tey could continue to red for another 2 to 4 years (until the v-notch grows out). This has been remarkably successful and has resulted in bigger, and more, lobsters . This scheme is embedded in legislation in both, Ireland and the UK and it is therefore illegal to catch and keep any lobster with a v-notched tail.

It is also illegal to land lobsters smaller than 87mm carapace length. i.e. the length between the back eye socket and the most posterior edge of the shell (see image).

Furthermore, it is strongly encouraged to return specimens that are larger than 127mm carapace length.

The current fishing methods by pots and creels are very selective so that undersized, egg-bearing females or immature animals can be returned to sea alive. This is also true for any by-catch such as dogfish and crabs which are usually alive when landed and can be returned to sea without harm.

Another advantage of this method it that is has no impact on the seafloor and low impact on the environment and other marine life. Turtles, basking sharks and some species of whale (in some areas) can become entangled in ropes used to keep pots buoyant, although this is very rare. The total number of pots used is determined by boat size, the number of crew and the fishing ground.

New regulations were introduced in 2018 by the Sea Fisheries Protection Authority (SFPA) to protect the licensed fishing industry which has faced increasing competition in recent years from unlicensed or unregistered vessels that were operating on a commercial or semi-commercial basis and ensures the sustainability of this trade. Under these new regulations, any member of the public, who fishes for lobster and crab can only do so from 1st May to 30th September. The number of pots is limited to six pots, and one can only retain five crabs and one lobster daily. Crabs or lobsters cannot be stored at sea or sold or offered for sale to anyone – it is private consumption only. Previously there was no limit on the number of pots recreational or private fishers could fish or the times of the year when lobster or crab fishing could take place. This threatened not only the commercial fishing industry, but also the lobster stock.

Sustainability of crab fishery in Ireland

Even though crab meat is more affordable than lobster meat, currently, there is a debate on how sustainable the Irish crab fishery is. In May 2017, Bord Iascaigh Mhara (BIM) launched the Fishery Improvement Project for Ireland’s Brown Crab Fishery. This is to improve the sustainable operations within the fishery and to progress to certification under the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) over a 3-5-year period. Good progress has been made so far.

Generally, pot fishing is considered sustainable as it is selective for larger individuals and has minimal impact on the surrounding environment. Turtles as well as basking sharks and some species of whales may become entangled in ropes used to buoy pots, but it is very rare.

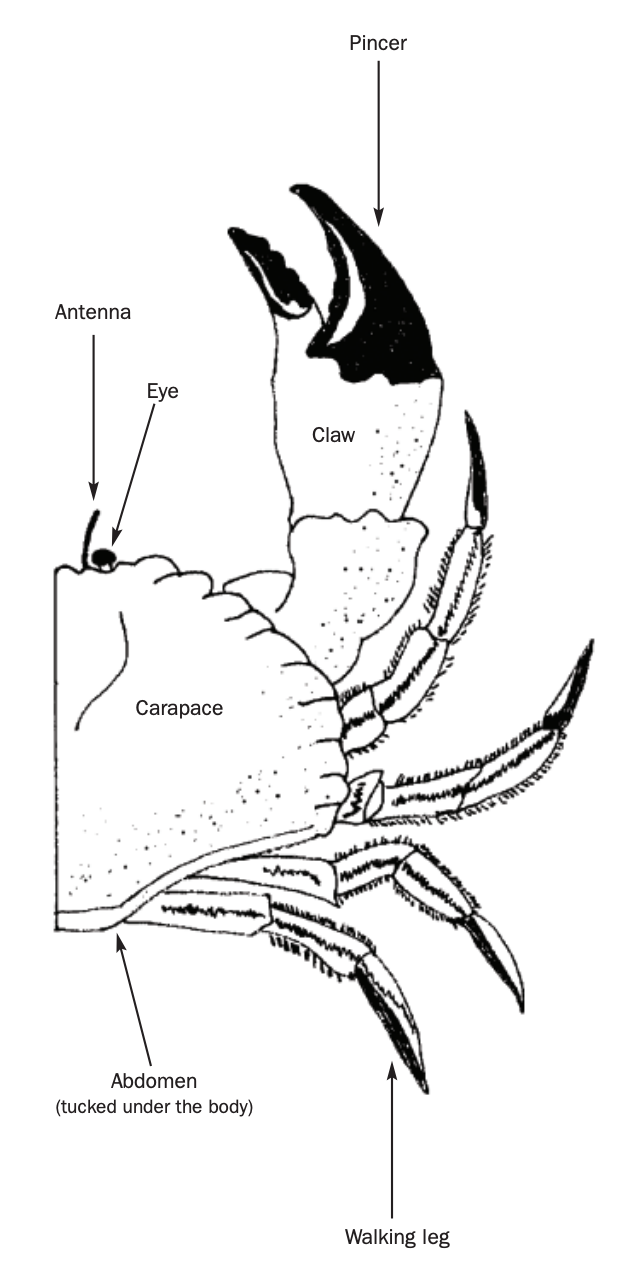

Pots are also a highly selective method of fishing which makes it possible to return undersized animals to the sea alive. However, many pots in use now, known as parlour pots, combined with mechanical hauling and increasing numbers of pots, have contributed to the potential unsustainability of the brown crab fishery in many areas. The legal minimum landing size for brown crab in European waters ranges from 14cm (north of 56 degrees North) to 11.5cm (Eastern Sea Fisheries District) depending on area of capture.

In coastal waters out to 6 miles, protection of berried females and soft-shelled crabs is ensured. There is a ban on using edible crabs as bait, a ban on the landing of claws only and gear restrictions.

Still, the stock in the Irish Sea is data limited and the stock status is unknown. There is concern for biomass (owing to lack of any data) but no concern for fishing pressure because landings per unit effort are increasing. Crab and lobster fisheries are not limited by EU Total Allowable Catch (TAC) regulations or national regulations, and are therefore not limited in the number of crabs they can take, although there have been moves by the EU to restrict the fishing effort such as restricted kW days at sea for boats over 15m.

New regulations were introduced in 2018 the Sea Fisheries Protection Authority (SFPA) to protect the licensed fishing industry which has faced increasing competition in recent years from unlicensed or unregistered vessels that were operating on a commercial or semi-commercial basis. Under these new regulations, any member of the public, who fishes for lobster and crab can only do so from 1st May to 30th September. The number of pots is limited to six pots, and one can only retain five crabs and one lobster daily. Crabs or lobsters cannot be stored at sea or sold or offered for sale to anyone – it is private consumption only. Previously there was no limit on the number of pots recreational or private fishers could fish or the times of the year when lobster or crab fishing could take place. This threatened not only the commercial fishing industry, but hampered the potential of the sustainability of the trade.