Rising islands and sinking seas in the Maldives - Dr Paul Montgomery's recent visit to the Maldives

Author Paul Montgomery

Visiting Research Fellow Trinity College Dublin and Senior Community Archaeologist MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology)

Figure 1. The shore at dusk on Fulidhoo (Dhivehi: ފުލިދޫ), Vaavu Atoll, Maldives. © Paul Montgomery

Understanding how communities interact with the marine environment is one of the main research goals of the Indigenous Peoples, Traditional Ecological Knowledge, and Climate Change: The Iconic Underwater Cultural Heritage of Stone Tidal Weirs Project. At the start of 2025, I had the pleasure of visiting some of the islands and atolls of the Maldives. The visit was an opportunity to investigate aspects of their maritime heritage and modern fishing methods in the context of climate change and the burgeoning economic growth being driven by tourism.

The concept of a “seascape” is an important element in any maritime nation’s sense of identity and culture. It relates to where and how people value their coasts. In the case of the Indian Ocean nation of the Maldives, the Maldivian cultural landscape is defined by its deep integration of every aspect of marine culture, evident in traditional practices like sailing, fishing, and architecture.

The Maldives consists of 26 natural atolls comprising approximately 1,190 islands, which are grouped into 20 administrative units. Currently, the Maldives are in the middle of a rising tourism boom, which contrasts sharply with the ecological challenges facing the region, with 80% of its islands sitting less than one meter above sea level, and the highest point of land is only 2.5 meters above sea level. Climate change, a rising sea level, coastal erosion, along with the impact of water temperature changes, are all affecting the ecological, cultural and historical seascapes of the Islands. The Maldives have some of the richest ecological marine zones on the planet, with a range of species of fish, marine mammals and marine plants that rival any ecological zone in the world (see figure 3.4.5).

Early historical narratives suggest that the Maldives were populated as early as 500 BC from mainland India. Subsequently, the area was referenced in historical sources ranging from the Roman empire, the Sri Lankan Mahāvaṃsa text and later Chinese sources for over 1000s years (1 & 2). During its history, the island has been home to Buddhist communities, a Muslim sultanate in the twelfth century and a mix of European powers (Portuguese, Dutch and British) from the sixteenth century onward till the establishment of the modern state in 1968 (3).

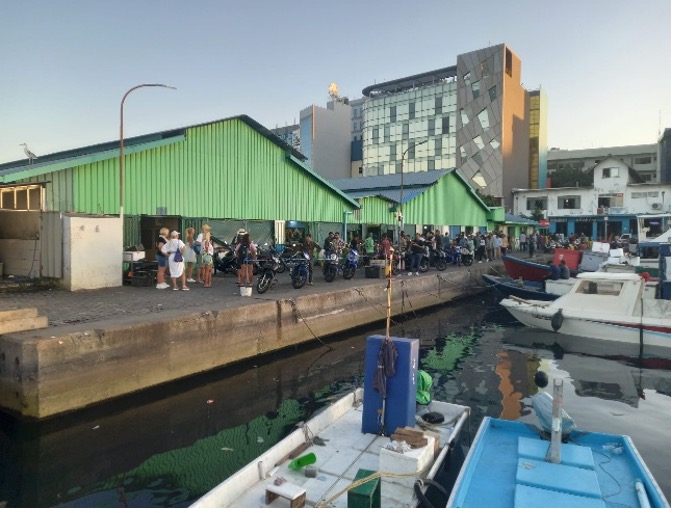

Figure 2. Picture of the fresh produce and fish market and the historical Galolhu Saharaa Cemetery, Malé, Maldives. © Paul Montgomery

In my research, the term “seascape” rather than landscape or the more traditional maritime cultural landscape is preferred as it better reflects the integration of reef, island and seabed (4). Today's scholars sometimes use the term “maritime cultural landscape”, coined by the father of the theory, Christer Westerdahl, to denote this zone of human and marine activity (5). The Maldives offers an insight into water-bound links and interpretations that have shaped a context of tangible and intangible heritage, history, anthropology, and archaeology. The focus of life, in every aspect, is shaped by the ocean's flowing and water-bound view of seascape as a part of their maritime culture and identity.

This approach allows for other significant aspects of the marine ecology of the Maldives to be brought into focus. The story of human interaction and the habitation of ecological niches across these islands is interwoven with the natural history and marine ecology of the region. Today, the economic landscape of the Maldives is in a state of flux as traditional fishing and maritime subsistence give way to the emergence of international tourism that has boomed in the last decade. This transformation is easily observed while walking around the “home islands”, that is, islands that have not been heavily impacted by urban development, like the capital, Malé. It's clear that the former marine-oriented communities, which relied on fishing and transported goods from island to island, are now heavily focused on tourist resorts and service providers for snorkelling and diving. The Island Fulidhoo (Dhivehi: ފުލިދޫ), Vaavu Atoll, Maldives, with a population of 300 to 400 people, is a prime example of this evolving economic context. Today, it has over 20 different hotels and guesthouses, and the bustling business of marine tourism is almost year-round. It brings with it a stress on the availability of food, fresh water, waste disposal and construction materials, impacting the local environment and marine ecology (6).

Today, several research projects are ongoing, examining the state and nature of the cultural heritage, such as The Maritime Asia Heritage Survey (MAHS), which digitally documents endangered historical and archaeological heritage across the watery world of coastal and island Southern Asia (7). The impact of sea level rise and its associated mechanical processes, such as powerful storm surges and heavy precipitation, is a danger to heritage sites and degrades cultural landscapes (8). The scale of ongoing reclamation and stabilisation so called ‘reclamation-fortification’ projects, fills the horizon as a scan of the islands reveals hundreds of ongoing projects (93.5 % of inhabited islands in 2020) to stabilise the existing islands and raise their level high above sea level (9). This mixes of tourism, infrastructure development and the scramble to fortify and stabilise many of the islands in the archipelago is a challenging environment in which to progress the study and preservation of the island’s cultural history and archaeology.

Beyond the many images of coral reefs that fill our holiday pictures, there is another less picturesque world, that involves the intensive fishing and processing of Tuna. The Maldives effectively utilises its marine resources by supporting artisanal fishers with carrier vessels, onshore processing, and cold storage facilities (10). The Maldives practise a traditional pole-and-line method for skipjack tuna Katsuwonus pelamis and sometimes Yellowfin tuna Thunnus albacares. All the tuna in the Maldives is caught using traditional, low-impact methods of pole fishing with baited hooks. In-person visits to the fish markets of the capital, Malé, confirm much of the research about the island fishery, with almost 2/3 of the fish on display being from the tuna family. The rest of the fish on sale at the market represent a wide variety of species, predominantly from the coral reefs, with leopard coral groupers (Plectropomus leopardus), cobias (Rachycentron canadum) and other species mixed in (see Figure 4). Despite the popularity of salted fish and tuna, many of the species of reef fish landed and traded on a day-to-day basis are coral-dependent species, which appear not only in local fish markets but are regularly served up in restaurants and hotels across the Maldives.

Within every seascape, there is a narrative that is indelibly linked to the way humans interact and perceive the natural environment around them. Coastal ecosystems of the Maldives are at risk from numerous threats ranging from the local to the global. The approach to sea level change such as the ‘reclamation-fortification’ approach for island stabilization has detrimental impacts on the environment (11). The range of stressors impacting this region includes a mix of economic development, changing sea levels, climate variability, and unregulated fishing practices. Going forward, the Maldives is looking for solutions that can balance development and growth while respecting the seascape in the face of these major challenges. Age-old fishing traditions continue ‘cheek to jowl’ with modern tourism in the Indian Ocean basin.

Bibiolgraphy