History of the Cod in Ireland

A fish that shaped the world - Gadus morhua - 'Trosc' in Irish is of gave historical importance. The exact beginning of the cod fishery in the North east Atlantic is not known. However, zooarchaeological evidence has allowed researchers to pinpoint the birth of intensive marine fishing in northern Norway to the beginning of the tenth century AD. Dried cod was traded around the North Sea from that time on.

A fish that shaped the world - Gadus morhua - 'Trosc' in Irish is of gave historical importance. The exact beginning of the cod fishery in the North east Atlantic is not known. However, zooarchaeological evidence has allowed researchers to pinpoint the birth of intensive marine fishing in northern Norway to the beginning of the tenth century AD. Dried cod was traded around the North Sea from that time on.

Cod became one of the most sought-after fish in the North Atlantic, and it was its popularity that caused its enormous decline and the disastrous situation today.

The cod fishery in the old world

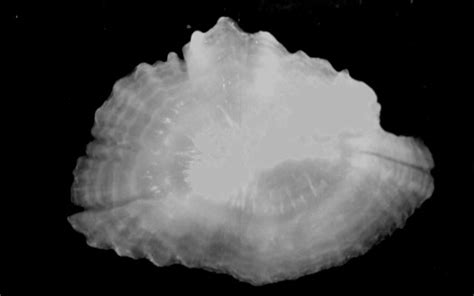

While cod fishery started to become increasingly important in the ‘old world’ around the 13th – 14th century, the University of Maine found evidence that Indigenous peoples on the other side of the North Atlantic consumed cod long before Europeans arrived and "discovered" the Grand Banks with John Cabot in 1497. For example, cod bones such as otoliths are found in middens of the Passamaquoddy tribes in eastern Maine among soft-shell clams, sturgeon and swordfish bones suggesting that cod was an important part of Indigenous peoples' diets.

Back in Ireland there is archaeological evidence that cod was also part of the hunter-gatherers diet in Mesolithic times (c. 10,000 years ago). Sites such as the Ferriter’s Cove in Co. Kerry show an abundance of cod, haddock, ling and other fish bones among shellfish middens from limpets, oysters, cockles and scallops.

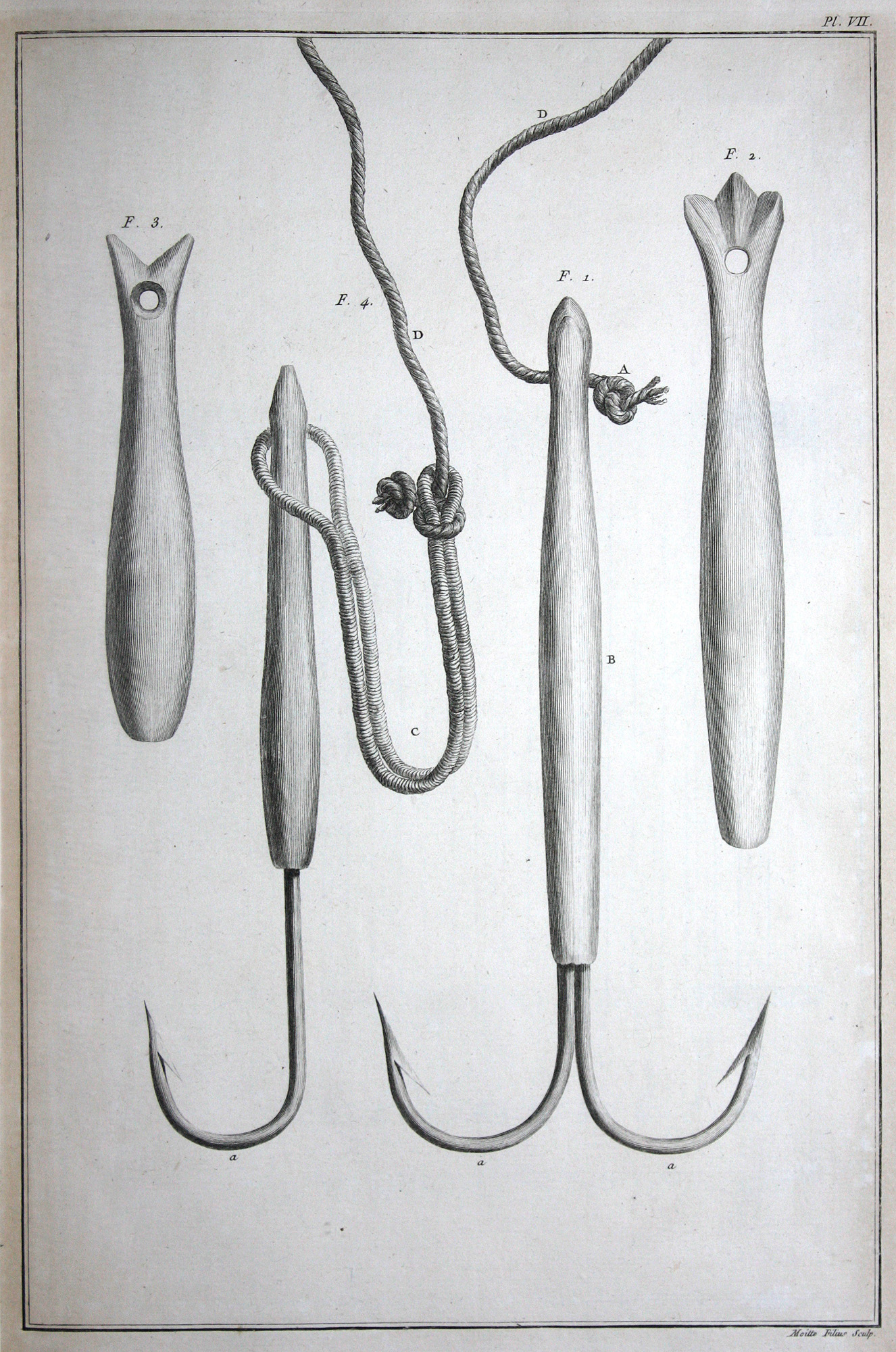

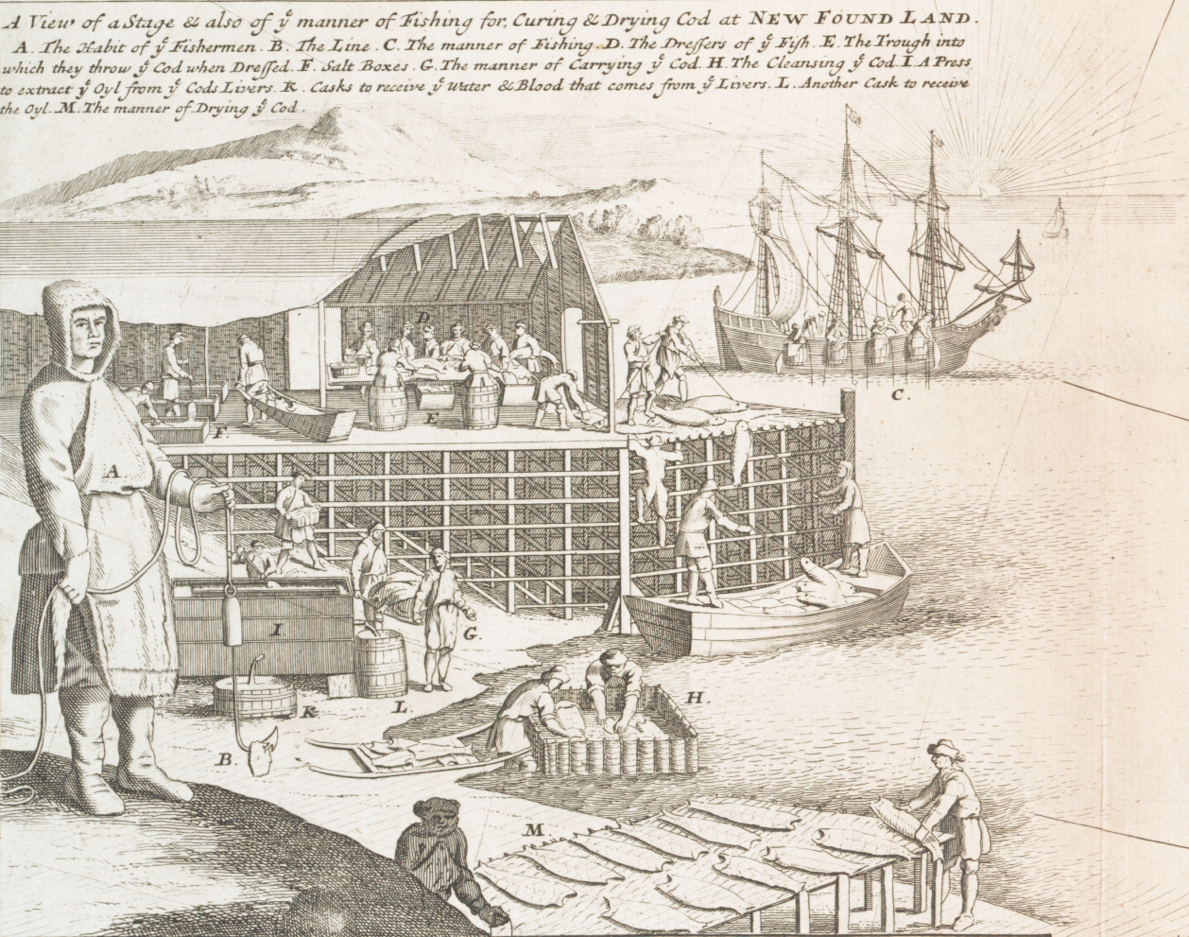

Traditionally cod was caught by hook on a single line. The hook size determines the size of the cod you can catch and is a good way to ensure that you don't catch undersized fish. These were simple measures to sustain the constant cod supply.

Fresh cod was commonly utilized in its entirety. And while the fillets were valued in more recent times, it was the cod head, especially it’s cheeks and tongues (throat muscles) and the collar that was sought after. Many historical recipes also include cod sounds which are the air bladders located alongside the spines of the fish.

The cod trade

The trade of fresh cod was in high demand and a lot of effort was made to transport the fish to the markets alive. It was soon realised that the fish would die rather quickly when taken out of its marine environment. Therefore, the Dutch transported their live cod catches in ships with perforated bottoms allowing a constant flow of saltwater and hence delivering live and fresh cod to the markets of the big sea cities. The English were even more creative and pinched the air bladder of each cod with a needle, forcing them to stay at the ship’s perforated bottom ensuring them to stay alive longer.

An alternative to fresh cod, was the dried version of this nutritious fish since the early medieval times referred to as ‘stockfish’ ever since. Cod prepared this way ensured a nutritious meal and lasted up several years.

When salting fish became feasible on a large scale, cod was also salted and dried. At the start of the 16th century cod became a hugely important commodity and salted and dried cod was traded for grains such as wheat and rye.

The salted and dried cod was popular in countries such as France and Spain, while the stockfish remained popular in Germany. By the 18th century the Norwegians developed a new salt/drying method which became popular throughout Europe and cod prepared this way became known as ‘klipfish’ (although the name has been in use for much longer).

The Portuguese still prepare their ‘bacalhau’ the same way they did over 350 years ago.

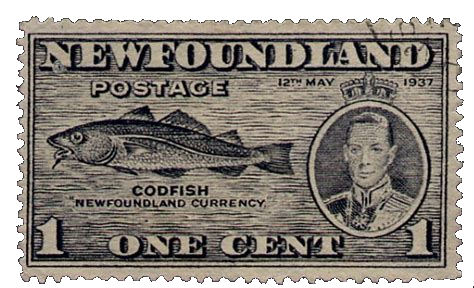

The cod fishery in the new world

The discovery of the Grand Banks in the early 16th century changed the western world dramatically. Fish was no longer a highly prized product, but a commodity that the common folk could affort. If you're interested in reading more about the effects of the discovery of the Grand Banks and with it the vast amount of cod, visit the NorFish project.

Ecology of cod

Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) is a benthopelagic fish (demersal) and possibly the most important member of the Gadidae family from a commercial perspective. The order Gadiformes contains many important food species generally considered cold-water white-flesh fish since they occupy the cold waters on both sides of the North Atlantic with a few species also inhabiting the Mediterranean.

There are four species in the genus Gadus across the globe: the Atlantic cod Gadus morhua, the Pacific cod Gadus macrocephalus, the Greeland cod Gadus ogac and the Alaska pollock or walleye pollock Gadus chalcogrammus.

Cod distribution

The Atlantic cod is divided into several stocks, inclduing the Arcto-Norwegian, North Sea, Faroe, Iceland, East Greeland, West Greenland, Newfoundland and Labrador stocks. There doesn't seem to be much interchange between the stocks, although each stock can travel great distances to get to their individual breeding grounds.

In Irish waters, cod is found in the western Irish Sea as well as the Celtic Sea along the Cork coastline. Juveniles are commonly found in depth of 30 to 80 m, mainly on rocky bottoms while adults tend to live in deeper regions along the continental shelf.

In past centuries cod would have commonly grown as big as 150cm weighing up to 45kg, however, nowadays the usual size is between 50cm and 110cm in length with weight no more than 35kg. The species can live up to 25 years while sexual maturity is reached between age two and four, although it can take up to eight years for the race in the Northeast Arctic to mature fully.

Reproduction cycle of cod

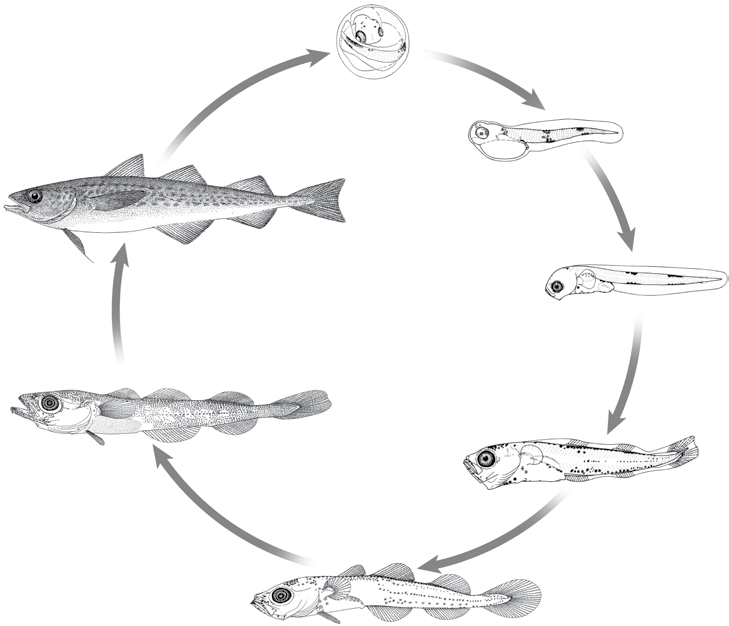

The Irish cod is very fast growing and attains lengths bigger than 35cm in the first year and often over 90cm as adults. Half of the individuals are mature at 2 years and 100% have reached maturity by the age of three.

There is evidence that suggests that female cod actively choose a spawning partner based on the sound that a male cod makes and other sexually selected characteristics.

A mature adult female can produce over 2 million eggs and spawning usually occurs in winter and early spring in big aggregations in offshore waters, at or near the bottom, in 50-200 m depth and 0-12 °C (preferred range 0-6°C). If the bottom temperatures are unsuitable, cod may form spawning aggregations in the water column. Embryo development lasts about 14 days (at 6°C) and the larval phase lasts about 3 months (at 8°C). Older and larger cod had been found to produce larger eggs with neutral buoyancy at lower salinities which can be crucial to egg and larval survival. Larvae are pelagic up to 2.5 months before settling on the bottom.

Cod feeding behaviour

Cod are omnivorous and feed at dawn or dusk on invertebrates and fish. The apex predator is also known to eat their young (cannibalistic). Stomach sampling studies have discovered that small Atlantic cod feed primarily on crustaceans, while large speciemens feed primarily on fish.

There are many anecdotes that cod eat whatever drops in front of their mouths and fishermen are known to have accidentally dropped their knifes into the water just to find it in the stomach of a cod they caught not much later.

G. morhua is a shoaling species that moves in large, size-structured aggregations. It was observed that larger fish act as scouts and guide the way of the shoal. This seems to happen particularly during the post spawning migrations to inshore feeding grounds. Cod do not have many natural predators, but juvenile fish (also called codlings) can be a food source for adults since the species is known for cannibalism.

Cod have been recorded to modify their activity pattern to the length of daylight and therefore activity changes throughout the seasons. Cod are one of the easiest fish to catch since they shoal in great numbers in places with the least flow of currents.

This is most likely linked to its temperature sensitivity. Cod typically avoid new temperature conditions, and the temperatures can dictate where they are distributed in water. They prefer to be deeper, in colder water layers during the day, and in shallower, warmer water layers at night. These fine-tuned behavioural changes to water temperature are driven by an effort to preserve energy. This is demonstrated by the fact that a decrease of only 2.5°C causes a highly costly increase in metabolic rate of 15 to 30%. Their low temperature tolerance makes them vulnerable to climate change.

Cod Trivia

Did you know that the Irish compared the colouration of the cod to that of Connemara marble.