Bog Cotton on the Dingle Peninsula. Photo by Caroline Kreysel

In the depths of the Bog

By Caroline Kreysel

There is probably no landscape as intertwined with Irish culture as bogs. Various historical practices in Ireland are long-term adaptations to the boggy surroundings, such as turf-cutting, the storage of bog butter, and the extensive pastoralism in the early modern period. Despite the close interaction between bogs and humans, humans in the past often understood bogs as eerie, a stage for illicit activities, and even a spreader of diseases. In the early nineteenth century, in various European countries bogs were drained and converted into “useful” agricultural ground to remedy their perceived uselessness. This, however, damaged the vital ecosystem functions that bogs fulfil such as storing CO2, being a habitat for multiple species and regulating water levels. In the inconspicuous depths of Irish bogs, therefore, lies an entire history of humans and the non-human world interacting and shaping each other.

For my thesis on environmental history, I decided to delve deeper into the bogs to find out what we can learn from their history of imperial knowledge-making and their position in the Anglo-Irish relations in the early nineteenth century. My supervisor Dr. Bruisch put me on the track of the Bogs Commission, a little-known organ of the Westminster authorities, which was hired between 1809-1814 to survey the Irish bogs and advise on the possibility to drain them and convert them into agricultural fields. In the wake of the ongoing Napoleonic Wars, the imperial government, and scientific authorities such as the Dublin Society and the Royal Society understood bogs as unused agricultural spheres that could render Britain resource-autarch.

Griffith, Richard jr. ‘Map of Part of the Bog of Allen. Situated in the County of Kildare Being the Eastern Division of District No. 1.’ ca. 1:40,000. The First Report of the Bogs Commission. London: Luke Hansard & Sons, 1810. Map courtesy of Glucksman Map Library Trinity College Dublin. I am grateful to the RePEAT-Project for making a digitized version of this map available to me.

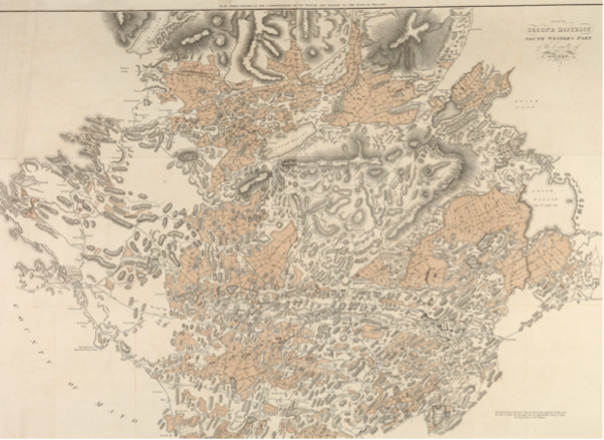

The Bogs Commission worked meticulously to record the extent, characteristics, and potential drainage methods for the bogs they encountered. They produced the most detailed reports and maps of Irish bogs of the time. The maps portrayed in detail the rural settlements in Ireland, turf banks and existing roads and waterways, thus providing a unique insight into the historic reality of pre-famine Ireland. In addition, their reports contained a variety of descriptions and sketches of geology, composition and suggested drainage schemes for the bogs. For example, a surveyor William Bald, who was dispatched to the County of Mayo, produced maps that in significant detail indicate the location and size of rural settlements along the coastline, detailing the augmenting subsistence crisis in Ireland in the wake of rapid population growth.

Bald, William. ‘Plate XV: Second District South Western Part of the County of Mayo’. ca. 1:40,000. Third Report of the Bogs Commission. London: Luke Hansard & Sons, 1814. Map courtesy of Glucksman Map Library Trinity College Dublin. I am grateful to the RePEAT-Project for making a digitized version of this map available to me

However, the Bogs Commission’s reports were not a neutral depiction of Irish bogs. The surveyors brought their own pre-conceived ideas about bogs to the regions they surveyed and assessed the Irish landscape mainly through the idea of bogs as potentially abundant agricultural resources. This determined their assessment of the value of rural communities, and of the land in general. The surveyors, however, encountered a reality that diverged from these imperial imaginations of bogs as wastelands waiting for imperial handling. Instead, they had to rely on local knowledge and ways of interacting with bogs to produce their maps and suggest methods to achieve their resource-burdened visions. For example, to navigate the bogs, the surveyors had to learn how to travel across them, relying on local knowledge on how to lead a horse across a bog without sinking or on how to construct portable railway tracks. They also continuously adopted their research methods and negotiated with the Commission’s board about the validity of imperial orders.

Through applying an environmental history perspective to these documents, I traced the non-human “writers” of the bog reports and maps. My research showed that bureaucratic processes that were supposed to enforce imperial control over the Irish environment were never complete but depended on various contingent influences. There was thus a dialogue between the non-human world, local populations, state officials and accepted scientific realities of the time that produced the knowledge recorded in the bog reports. By adopting an environmental history approach, I was explicitly seeking to understand imperial knowledge-making processes through the more-than-human interactions on the ground. This approach allowed me to challenge ideas about imperial hegemony and knowledge production, and to question the idea that humans unilaterally interact with the environment. In the wet and muddy realities of the bog, imperial hierarchies became less pronounced as local situations demanded creative responses from the Bogs Commission. Bogs, including their vegetation, fauna, and human inhabitants, were not merely a passive sphere for imperial projections but actors that leaked into human practices beyond their physical borders.

The Bogs Commission’s work did not yield any immediate policies to drain bogs, but it was used in later years to indicate bogs for turf cutting. While my research treated a seemingly small case study with limited impact in a considerably short period, the themes I identified bear relevance for the contemporary treatment of bogs. They show how economic interest in bogs had long-lasting repercussions and how science and imperial politics converged to control the rural Irish communities and the lands they inhabited. By taking the environment seriously as a historical actor, new understandings of imperial structures, valorizations of environments and historical contingencies can emerge, complicating existing historical knowledge and indicating alternative ways of interacting with the environment. By recognizing the human choices that diminished the number of intact bogs in Ireland, it might become possible to also envision a future of more sustainable human-bog interactions and relate to the ways in which Irish history is entrenched in the bogs in new ways.

Doing some fieldwork. Caroline at the restored Abbeyleix Bog, learning about the functions of Sphagnum Moss. Photo by Emma Finnamore.

Caroline Kreysel completed the MPhil Environmental History in the summer of 2022. She wrote a thesis on bog drainage in Ireland in the early nineteenth century for which she was awarded the TCEH thesis prize. She is particularly interested in historical land use, environmental knowledge-making processes and writing more-than-human histories. Starting in spring 2023, Caroline will be a PhD candidate at the Free University of Amsterdam (VU) studying the history of soy in agriculture in the Netherlands and Brazil.