The 21st century is defined by grand, interconnected challenges, and among them, the global biodiversity crisis stands out as one of the most urgent and defining. It's a crisis that transcends ecological boundaries, weaving its way into the very fabric of our economies, societies, and cultures. As Dr. Brian McSherry of the European Environment Agency (EEA) highlights, addressing this systemic threat requires a systemic solution, a conscious pivot towards truly multidisciplinary action. In an era defined by environmental upheaval, the message from Dr. Brian MacSharry could not have been clearer: the biodiversity crisis is too vast, too interconnected, and too urgent to be solved by any single discipline.

Speaking at Trinity College Dublin’s Balanced Solutions for a Better Planet webinar series, hosted by Michael Lynham, E3, Trinity College Dublin, Dr. MacSharry, Head of the Group of Nature and Biodiversity at the European Environment Agency, delivered a wide-ranging and at times sobering presentation on the state of global biodiversity. With more than 20 years of experience in conservation, his assessment is grounded in both scientific rigor and lived experience across local, European, and global projects.

The Triple Planetary Crisis

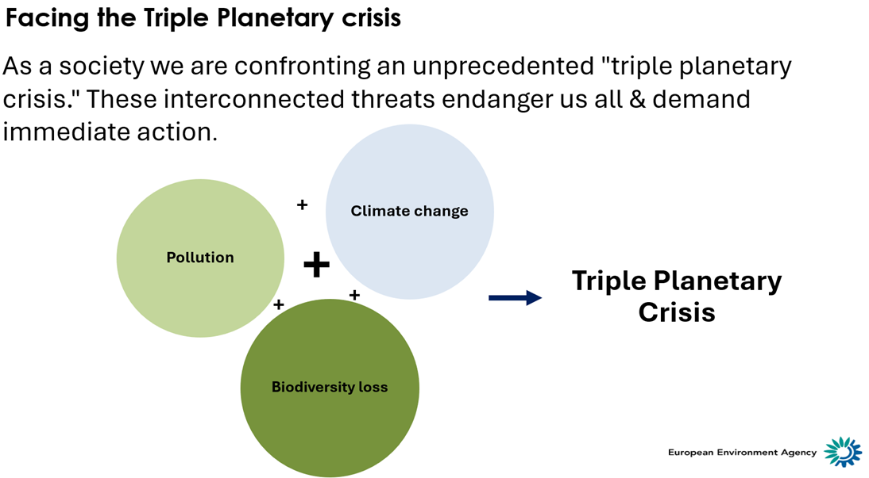

To understand the biodiversity crisis, we must first appreciate its context: it is but one head of a hydra known as the triple planetary crisis. This term, popularised by the UN Secretary-General, underscores the simultaneous, interconnected, and mutually exacerbating threats of the Climate Crisis, Pollution Crisis, and Biodiversity Crisis.

Dr. McSherry frames the interconnected nature of these problems succinctly:

“We're really in this situation where we've got a climate crisis, pollution crisis and a biodiversity crisis, and this is going to turn the triple planetary crisis... But really what it's saying is that we have these different issues happening to us, but they're interconnected, they can't work in one well, one view what we have to connect all of those.”

The solutions to one invariably involve tackling the others. The loss of biodiversity, for instance, reduces nature’s capacity to sequester carbon and purify water, thereby worsening both the climate and pollution crises. This recognition of deep interconnectivity is the first step toward embracing a multidisciplinary mindset.

Why Biodiversity is Not a Luxury

Nature, or biodiversity, the living part of our planet, is often viewed through a purely environmental lens, but Dr. McSherry stresses that it is, in fact, the fundamental pillar of our existence. As EEA Director Leena Ylä-Mononen stated, “Nature is not a luxury; it’s a must-have and it underpins everything we hold.”

The financial dependency on these services is staggering. The World Economic Forum (WEF) estimates that about half the world’s GDP, valued at some $44 trillion—is moderately or highly dependent on nature. Furthermore, European Central Bank analysis shows that around three million companies in the Eurozone rely on at least one ecosystem service, impacting 75% of bank loans to those companies. The risk is clear: lose nature, and you risk economic collapse.

Dr. McSherry noted the shifting discourse in the economic sector:

“The World Economic Forum did some work a few years ago where they started using the language of GDP and economy to highlight the value of biodiversity... this is the World Economic Forum talking about this is not the word Biodiversity Forum saying. So what I've noticed a lot of last few years is the narrative coming from different sectors.”

Ecosystem Services in Focus

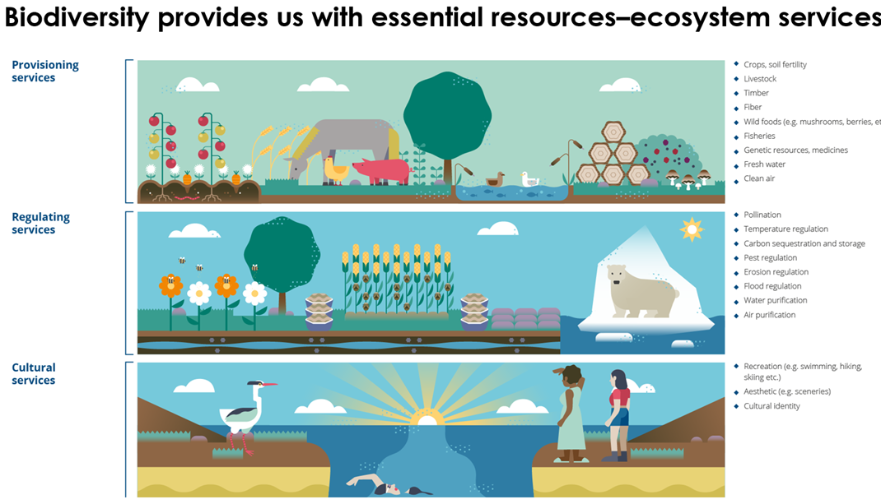

The value of nature can be broadly grouped into Ecosystem Services:

• Provisioning Services: Direct products like fresh water, clean air, timber, and livestock.

• Regulating Services: Benefits from regulation, such as pollination (estimated to contribute about €15 billion to the EU's annual agricultural output), carbon sequestration, and water purification.

• Cultural Services: Non-material benefits, including the recreational and profound cultural identity linked to places like the bogs of Ireland.

The State of Nature in Europe

The European Environment Agency’s State of Nature Report provides the stark evidence of the crisis.

The findings are unambiguous:

• Habitats: Around 81% of habitats (including forests, peatlands, lakes, and sand dunes) are in poor or bad condition, with a decreasing trend.

• Species: Nearly two-thirds of the species assessed are also in poor or bad condition, with approximately two-thirds showing unknown or decreasing trends.

For a country like Ireland, which is dominated by agricultural land and managed forests, the figures are even more concerning, with around 85% of its nature in a poor or bad condition.

The Cost of Lost Resilience

Biodiversity loss translates directly into increased risk across multiple sectors. As Dr. McSherry noted, describing the systemic impact of environmental decline:

“I suppose in two words it's increased risk, increased risk to our economy, our health, our society, ourselves.”

The risks are tangible, from the volatility in cocoa prices due to climate shocks to the failure of energy infrastructure, such as nuclear power stations in France halting operations because water levels were too low, and temperatures were too hot.

Furthermore, there is a clear social dimension to the crisis:

“...the burden of this discrepancy and health benefits is not equally shared among society. Richer areas tend to have better quality environment. Poor areas tend to have poor quality, and the poorer areas of society tend to get more adversely affected by this.”

Policy and Restoration

Europe is actively responding with key policy instruments:

• EU Biodiversity Strategy (2020): Sets ambitious targets, including protecting 30% of Europe's land and sea.

• Nature Restoration Law: This pivotal regulation mandates that EU member states actively restore nature. It sets a 2030 target of having plans in place to restore 20% of Europe’s land area and ensuring that everything that needs restoration has a plan by 2050.

Dr. McSherry reflected on the difficult political journey of the Restoration Law:

“The agenda and restoration got kind of a bit hijacked by politics... what went from being kind of a given as in everyone agreed to it, certainly it became something very, very political.”

The Multidisciplinary Imperative: Doing Enough?

Despite these policies, the pace of recovery is insufficient. Dr. McSherry soberly notes that we are “probably not reversing biodiversity loss as much as I would personally expect.”

The fundamental reason for this lies in the initial framing: the biodiversity crisis cannot be addressed purely by biodiversity policies.

“I think it's because you can't address the biodiversity crisis purely by biodiversity policies, by biodiversity actions, as biodiversity underpins our entire society. You kind of need a whole society approach to dealing with this and that by default means that we have to have a multidisciplinary approach.”

To achieve the necessary systemic change, the work must move beyond the traditional realms of conservation science. Dr. McSherry’s own network demonstrates this essential plurality, extending from zoologists, geographers, and data managers to AI experts, High Court judges, economists, anthropologists, and religious leaders.

The Need for Shared Language

Success hinges on the ability of people from all these diverse fields to communicate effectively, understand different perspectives, and align their actions toward a common goal.

“A lot of that for me translates to in order for me to achieve success in what I'm doing, I need to work with people. Lots and lots of people from lots of different backgrounds, countries, cultures and with their own different perspectives and language that they use to describe things. And I think there's a clear need for all of us to be able to understand each other.”

The imperative is clear: every profession, law, finance, technology, or agriculture, must recognise that the fate of biodiversity directly impacts, and is impacted by, their work. This is the essential plurality required to move beyond merely slowing the decline and finally begin building a more sustainable and equitable world.

Participants were left with a challenge: to think about biodiversity not as a standalone issue, but as a lens through which all other sustainability questions must be viewed.

Dr. MacSharry’s message was unmistakable: "To protect nature, societies must rethink how knowledge is produced, how decisions are made, and how disciplines collaborate".

The biodiversity crisis, he reminded the audience, is not just an ecological emergency, it is a human one.