The transition to a sustainable and equitable global future hinges on a fundamental shift in how we conceive, produce, and consume materials. This was the central, electrifying theme of a recent online event hosted by E3, entitled “Cross-Sectoral Themes and Collaborations to Support Circular Material and Product Innovations,” featuring the insightful Dr. Aimee Byrne. The webinar, gracefully introduced by Ruth Clinton, the Industry Engagement and Partnerships Manager at E3, underscored an urgent move away from the destructive ‘take, make, and dispose’ model and towards a regenerative, closed-loop system, a concept Dr. Byrne expertly described as a sort of ‘sustainability 2.0.’

The event commenced with a crucial outline of the E3 vision itself, a strategic, multidisciplinary expansion across Trinity’s schools of Engineering, Natural Sciences, and Computer Science and Statistics. This is not a mere facilities upgrade, but a unified strategic activity focused on engineering, environment, and emerging technologies. The core recognition is that solving the colossal challenges inherent in sustainable development absolutely demands a multidisciplinary approach. This spirit of breaking down traditional silos, as Ms. Clinton highlighted, perfectly framed the day’s subject: the transition to a circular economy is fundamentally a collaborative enterprise, one where sharing resources and knowledge across traditionally separated sectors can unlock the most potent and highest-value innovations. Think of the potential, for example, in transforming low-value construction waste into a high-performance input for the electronics industry; this is where the real innovation engine ignites.

The Unavoidable Need for Circularity

Dr. Aimee Byrne, an E3 Assistant Professor in Climate Adaptation Engineering in the School of Civil, Structural and Environmental Engineering at Trinity College Dublin, brought a wealth of foundational expertise in sustainable building and circular construction to the discussion. Her presentation began by laying bare the necessity of this shift. Every major policy and business statement now mentions the circular economy because the current linear model is simply unsustainable.

Dr. Byrne effectively framed the core common principles across all sectoral definitions of circularity: the necessity to eliminate waste and pollution, to circulate products and materials at their highest value, and perhaps most importantly, to actively regenerate nature. She positioned circularity as an aspirational goal, moving beyond simply reducing impact to aiming for zero: zero waste, zero pollution, and zero resource depletion. This resilience-focused systemic change is designed to decouple economic growth from the use of newly extracted raw materials, allowing humanity to consume and thrive without destroying the planet’s resource base.

The evidence for this necessary change is overwhelming. Dr. Byrne cited the triple planetary crisis, climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution, and identified unsustainable patterns of consumption and production as the unifying thread. Resource extraction and processing are startlingly responsible for over half of global greenhouse gas emissions, almost all biodiversity loss and water stress, and forty per cent of particulate matter pollution. Currently, the world is operating well beyond its means, requiring 1.7 Earths to replenish what is consumed annually. The disparity is even more acute in places like Ireland, where the consumption rate would demand 2.6 Earths if universally adopted, underscoring a national borrowing from both future generations and developing nations.

Mapping Resource Extraction and Waste

To focus effort, Dr. Byrne detailed global material extraction trends, showing how non-metallic minerals (sand, gravel, and clay, largely for the construction sector) account for almost half of all extracted materials and represent the largest area of growth. This is followed by biomass (bio-based materials like crops and residues) and fossil fuels. Importantly, the construction sector, followed by the food industry, uses the greatest volume of these extracted materials. Grouping the built environment, mobility, and the food industry reveals that these three sectors alone account for a staggering 90% of resource extraction.

However, as Dr. Byrne rightly noted, these tonnage statistics do not tell the whole story of sustainability. While construction and demolition waste is the largest single waste contributor by weight, other sectors, such as textiles, generate disproportionately high waste and have highly documented exploitative practices.

Looking at Ireland’s material reuse rates, which are reported to the EU in four categories (construction, textiles, furniture, and electricals), the overall rate is roughly 10.6 kilogrammes per person, slightly below the EU average of 13 kg. More critically, Dr. Byrne’s analysis of the data revealed a crucial distinction: in construction, while a huge amount is being reused by weight, very few full units (like a reusable door or beam) are being circulated. Most of the reuse is ‘downcycling’—crushing materials like concrete for use in low-value applications, such as under roads. This process tragically sacrifices the inherent value, energy, and strength of the original material.

Guiding Principles for a Circular Future

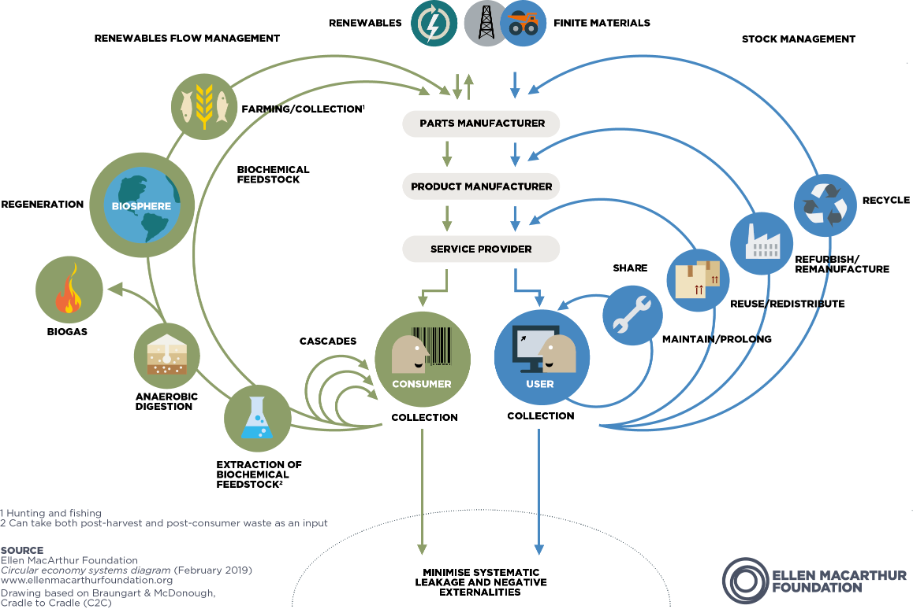

In the face of complex, sometimes misleading data, Dr. Byrne offered a suite of practical principles to guide better decision-making, starting with the iconic Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s Butterfly Diagram.

This diagram elegantly splits the circular economy into two primary cycles:

-

The Technical Cycle: Focused on non-natural materials and the strategies of reuse, repair, and remanufacture.

-

The Biological Cycle: Focused on biodegradable nutrients that can be safely returned to the earth to regenerate nature.

The key takeaway from the concentric circles in the diagram is the imperative to stay in the innermost loops for as long as possible, doing as little to the product as possible. For a mobile phone, this means maintenance and sharing, then remanufacturing, and only moving to the outer loop of recycling as a last resort. Recycling, while often perceived as the ultimate circular act, is actually very low on the hierarchy because it involves breaking the product back to its fundamental parts, expending significant energy, producing more waste, and losing all the value and embodied carbon associated with the original form.

In the Biological Cycle, the focus is on regeneration. Once food is harvested, the organic waste stream nutrients can be collected and returned to the soil through composting. Furthermore, processes like anaerobic digestion convert biomass feedstocks (slurry, grass cut-offs, food waste) into biogas and digestate, which can be used as a chemical-free soil improver. Ireland has an ambitious target to derive 10% of its natural gas from biomethane (a form of biogas) by 2030, which will necessitate significant investment in new plants.

The Power of Cascading and Valorisation

Dr. Byrne then introduced the cascading principle, which originated in the forestry industry but is applicable to any biomass source.

The principle advocates for the consecutive exploitation of resources for multiple ends, moving from the most solid format (e.g., solid timber) through progressive phases of reusage (e.g., wood fibres, particulate boards, chemicals) before the final, lowest-value step of energy production (burning).

This leads directly to the valorisation hierarchy, which clarifies what constitutes 'highest value.' Generally, this moves from medical/health products (pharmaceuticals) down through survival-related uses (food and feed), into high-end materials (bioplastics, polymers), bulk chemicals (ethanol), and finally, at the very bottom, energy and heat. A high-value circular action takes a waste product and uses it in a higher form, preventing the downcycling of valuable resources into low-grade applications. An example of poor valorisation is Irish sawmills typically burning timber residues for on-site heat, a low-value end use for a potentially versatile resource.

The 10 R’s Strategy

Building upon Ireland’s traditional ‘Reduce, Reuse, Recycle’ campaigns, Dr. Byrne detailed the modern, more comprehensive 10 R’s strategy, which further refines the hierarchy of circular actions.

| Hierarchy Level | 10 R Strategy | Construction Examples |

| Highest Value | Refuse | Reject unsustainable materials or processes. |

| Rethink | Redesign the use function, e.g., using a product-as-a-service model. | |

| Reduce | Optimise material use in design. | |

| Reuse | Reusing a product for the same purpose, e.g., a full door. | |

| Redistribute | Selling on a full product to a new user. | |

| Mid Value | Repair | Fixing a component, e.g., replacing a window pane. |

| Refurbish | Upgrade and restore to near new condition. | |

| Remanufacture | Rebuilding a product from recovered parts (like a mobile phone). | |

| Lowest Value | Recycle | Processing waste into a raw material, e.g., crushing concrete. |

| Recover | Energy and heat recovery from residual waste. |

This expanded hierarchy clearly demonstrates the effort to keep materials and products in use at their highest value for the longest possible duration, with recycling and energy recovery positioned, again, as the least desirable, final steps.

A Just Transition

Finally, Dr. Byrne introduced essential additional rules to guide innovation, ensuring that circular solutions are not just ecologically sound but socially responsible:

-

Food First Principle: Priority must be given to food and nutrition security. Resources and land that could be used to feed people should not be diverted into non-food products, such as furniture.

-

Critical Raw Materials (CRM): The EU’s list of CRMs highlights materials that are low in volume but high and growing in demand, especially for the digital technology and renewable energy sectors. Innovation must focus on replacing or recovering these scarce materials from existing waste streams.

-

Safe and Sustainable by Design: This framework guides innovation to minimise environmental impact and risk to human health across the entire lifecycle, from manufacturing exposure to end-of-life contamination.

-

Just Transition: Crucially, any climate solution must not negatively affect different socio-economic groups. Circularity cannot be achieved at the expense of equity.

Dr. Aimee Byrne’s event was a compelling and comprehensive primer on the circular economy. It served not only to define the principles but also to demonstrate, through concrete examples, that the successful transition hinges on multidisciplinary, cross-sectoral collaboration, driven by a clear understanding of material value and the pursuit of regenerative, zero-impact systems. The time for the old, linear model has run out; the future is circular, and the opportunity for high-value innovation has never been greater.