Oliver Goldsmith

David O’Shaughnessy

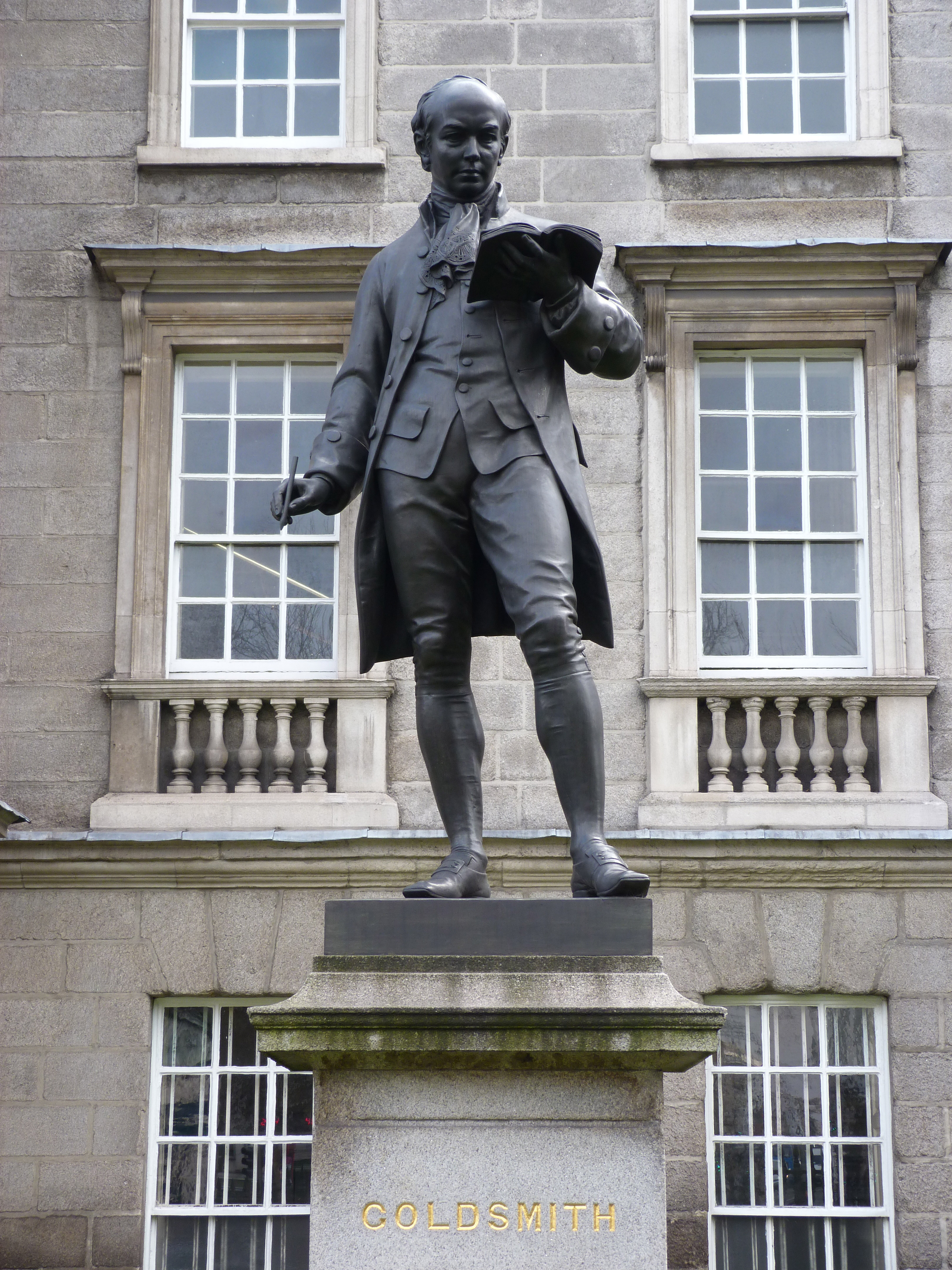

Entering the front gate of Trinity College Dublin, visitors pass between two bronze statues. On the left stands Edmund Burke, one of the great statesmen of British parliamentary history and often nodded to as the finest writer of political prose in the English language. On the right stands Burke’s friend, Oliver Goldsmith. The sculptor’s depiction of Goldsmith is suggestive: whereas Burke’s imperious gaze sweeps across College Green, Goldsmith, with a pen poised in his right hand, is engrossed by the book he is reading. There is a teasing uncertainty in John Henry Foley’s nineteenth-century statue. Is Goldsmith editing one of his own well known literary works? Or is he rather highlighting passages from the work of another writer for his own subsequent use? For, while Oliver Goldsmith authored works of considerable originality, like many eighteenth-century writers he also engaged in copious hack work for which he was paid by the word, churning out copy for a burgeoning literary market. What marks Goldsmith out from his contemporaries, however, is his distinctive claim to having penned masterpieces—as recognised by both contemporary and modern readers—in poetry, prose fiction, and drama. The shy, physically unprepossessing immigrant from the Irish midlands, buried in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey, received in his lifetime and still retains critical recognition across a range of genres.

Goldsmith was the son of a Protestant clergyman and was brought up in Lissoy, Co. Westmeath. He showed academic promise as a child but when Goldsmith arrived at Trinity College Dublin in June 1745 the immediate auguries for his student years were not good. Thanks to his father’s mismanagement of the family finances, Goldsmith arrived in Trinity as a sizar, rather than a fee-paying pensioner as his older brother Henry had been. A sizar, unlike fee-paying pensioners or fellow commoners (who paid supplementary fees in exchange for privileges), received financial assistance in return for carrying out certain chores, often for their fellow better-off students. In the class conscious eighteenth century this meant that Goldsmith had a tough time of it, and was a target for his peers’ disdain. To add insult to injury, the red caps sizars were obliged to wear meant that their receipt of charity was constantly publically paraded.

Goldsmith’s university troubles did not end with his financial indigence. His father had requested that Dr Theaker Wilder, whose scholarship he admired, be his son’s tutor. Wilder had just become a Fellow of the College in 1744 and would later go on to become the first Regius Professor of Greek at Trinity in 1761 (Trinity holds four Regius i.e. Royal Professorships: Physic, Laws, Greek, and Surgery). Wilder, a mathematician and character about campus, and Goldsmith, who was not mathematically inclined, did not get on. Years later, Goldsmith would recall that ‘his tutor was the most depraved profligate and licentious being in human shape’ (Wardle 1957, 32). Admittedly, Goldsmith does not appear to have done himself any favours: Wilder once challenged Goldsmith by sarcastically asking him in the middle of a lecture, ‘Where is your centre of gravity?’ to which the plucky (but very foolish) Goldsmith replied ‘According to you it would appear to be in my arse’ (Ginger 1977, 54). The relationship’s nadir was reached when Goldsmith held a party to celebrate an academic success. The ever vigilant Wilder came in to close it down and the ensuing altercation ended with him knocking Goldsmith to the floor. The young Goldsmith responded by storming out of Trinity and heading for Cork with, apparently, the intention of emigrating to America. But the wounded scholar had not quite thought this through and the inadequate resources (one shilling) with which he had left Dublin meant that his brother Henry was able to persuade him back to Dublin and Trinity and a reconciliation—of a sort—was reached with Dr Theaker Wilder.

In 1750 Goldsmith was finally free of his pedagogical nemesis. He left the College with his BA and without, it is safe to surmise, much regret, at least on the academic front. His time in Trinity had not been without diversion though—he had become involved in theatrical circles and, less fortuitously, developed a love of the gaming table, an addiction which would trouble him all his life. In 1752 Goldsmith headed for Edinburgh to study medicine and then followed this by a period in Leiden. But his attempts to keep his family happy by finding a profession petered out and in February 1755 he travelled on foot through Flanders, France, Switzerland, Germany, and Italy, a journey which later inspired his first significant poem The Traveller, or a Prospect of Society (1764).

After his European wanderings, Goldsmith arrived in London in 1756. He was now in his mid-twenties, impecunious, and with little in the way of career prospects. Moreover, that he was an Irishman in London added another possible impediment to his aspirations. There was undoubtedly anti-Irish sentiment in mid-eighteenth century London but the situation had improved markedly over the previous century, when lurid tales of Irish Catholic barbarity during the wars of the 1640s were engrained in Protestant Britain’s consciousness. By the 1750s, however, the British view on the Irish had softened considerably, not least as a result of the unpopularity of the Scots in the wake of the 1745 Jacobite rebellion, and the growing dependence of the British army on Irish recruits (1756 saw the beginning of the Seven Year’s War, the first British war in which this dependence became critical). There was also public recognition of a notable Irish contribution to London’s cultural and intellectual activities through prominent figures such as Edmund Burke, Charles Macklin the actor and playwright, and Arthur Murphy the journalist and playwright. More generally, there was a considerable body of Irish lawyers, doctors, merchants, and lobbyists now operating in London; the Irish diaspora had become part of the fabric of the city. The London that welcomed Goldsmith and other Irish of the ‘middling sort’ in the mid-eighteenth century was full of professional opportunities that no previous generation of Irish migrants had ever been offered.

In London, Goldsmith lived for a long time in the Middle Temple, where Irish trainee barristers, many of them graduates of Trinity, came to study law. Irish barristers were obliged to spend time at one of the four Inns of Court in London and, for most of the eighteenth century, the Middle Temple was the inn of choice. This was not least because the entrepreneurial proprietor of the adjacent Grecian Coffee-house, Samuel Coppock, was amenable to signing the bonds (guaranteeing the fees of Irish students) required for registration. This ensured the wily Coppock of their business and that of their acquaintance and the Grecian became well known as a place where recently arrived Irish migrants would congregate, confident that they might find a kind word and cogent advice to help them negotiate London (Bailey 2013, 78-86). Goldsmith ‘frequented much the Grecian Coffee-house [...] and delighted in collecting around him his friends, whom he entertained with a cordial and unostentatious hospitality’ (Mikhail 1993, 43). He was, as contemporaries testify, a friendly face for many Irish arrivals, from Trinity and elsewhere. Equally important, Goldsmith’s career became a resonant example of the success that was open to the ambitious Irish migrant to eighteenth-century London.

After something of a stuttering start, Goldsmith’s fortunes turned when he met publisher Ralph Griffiths in 1757. Griffiths had achieved a certain degree of notoriety for suspected Jacobite sympathies (that is, a supporter of the Stuart claim to the crown and the rebellion of 1745) and as the publisher of John Cleland’s pornographic Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1748-49). Griffiths took on Goldsmith for more staid employment, as a writer for the Monthly Review, a periodical dedicated to book reviews. Here Goldsmith reviewed Burke’s Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas on the Sublime and the Beautiful (1757) among other texts before jumping ship to the Monthly’s rival, the Critical Review, edited by Tobias Smollett and Archibald Hamilton. Goldsmith’s involvement with ‘Grub Street’—an actual London street associated with hack writers the name of which had become a metonym for low quality or derivative writing—was extensive, particularly in the 1750s and early 1760s.

It was probably through Smollett that Goldsmith was introduced to Dr Samuel Johnson and so began a friendship that would benefit the Irishman enormously. Johnson was the leading man of letters of the day and often credited with making writing for money respectable. Best known today as the author of A Dictionary of the English Language (1755), Johnson gave a very public testament of his esteem for Goldsmith’s intellectual ability when he invited him to be one of the founding members of the Club.

The eighteenth century was the great century for clubs. Men and women (although mostly men) joined all sorts of clubs as the importance of ‘public opinion’ began to resonate in a more influential manner than ever before. Some clubs were public and open to all but others were more exclusive, invitation only affairs, and Johnson’s Club was the most exclusive of all. Comprising only nine members at the outset, the Club was a supper and conversational society which met weekly in Soho for the purposes of the rich and stimulating exchange of ideas. The membership was illustrious including Edmund Burke, the wonderfully named book collector Topham Beauclerk, the music scholar John Hawkins, and the painter and soon-to-be inaugural president of the Royal Academy, Joshua Reynolds. Goldsmith’s inclusion is very suggestive of Johnson’s respect for him as he was considered shy and awkward in company by most. Unlike Burke and Johnson, renowned conversationalists of the day, Goldsmith was prone to verbal gaffes and in James Doyle’s nineteenth-century portrait of the Club, we note that he is on the periphery of the group, with something of a disgruntled expression on his face.

It was Johnson’s review of The Traveller, including his claim that it was the best poem since the death of Alexander Pope, that would ensure the work’s critical success. In this lengthy narrative poem, the eponymous Traveller casts a sceptical eye across the civil societies of Europe and laments what he observes. Goldsmith bemoans the pan-European rise of luxury and the commensurate decline of society, a theme that would emerge again and again in his writing. For example, Holland is castigated for its debilitating excess of commercial spirit:

Even liberty itself is barter’d here.

At gold’s superior charms all freedom flies;

The needy sell it, and the rich man buys:

A land of tyrants and a den of slaves (l. 306-9)

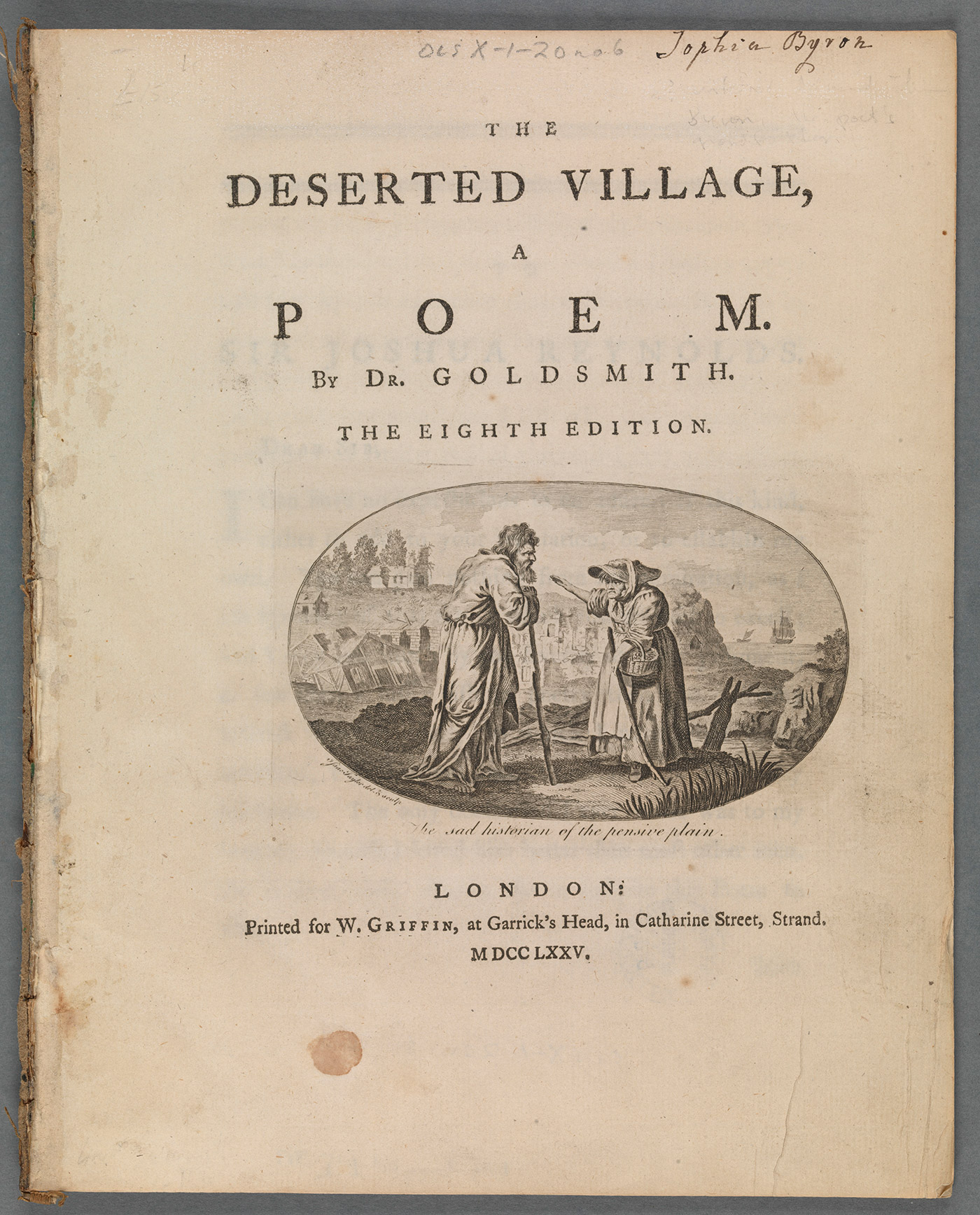

Johnson was not The Traveller’s only admirer. The poem received a number of critical accolades, Joshua Reynolds saying that it ‘produced an eagerness unparalleled to see the author’. The socialite Mrs. Cholmondeley, sister of the renowned Irish actress Peg Woffington, who had previously toasted Goldsmith as the ugliest man she knew, exclaimed ‘I never more shall think Dr. Goldsmith ugly’, a declaration that must have produced mixed feelings for the poet, if he heard it (Wardle 1957, 163). Despite the contemporary success of The Traveller, Goldsmith’s later poem The Deserted Village (1770) is probably now his best known. A paean to the virtues of those rural livings being destroyed by enclosure, that is, the eighteenth-century practice of privatizing common land, The Deserted Village has excited much comment related to Goldsmith’s politics and his loyalties. As an Irishman who was a firm (albeit less than enthusiastic) supporter of monarchy, Goldsmith has been viewed with suspicion by some Irish readers of a nationalist bent. On the other hand, there is a deep and persistent undercurrent in his letters and writing that looks back to Ireland and Irish culture with fondness. The location of ‘Sweet Auburn’, the titular village of the poem, has been central to these debates and produced much speculation: is it an Irish or an English village? It seems probable that Auburn is an idealized composite of Goldsmith’s experiences in both Ireland and England. Whatever its elusive politics, the Deserted Village is a poem of extraordinary power and one that revitalized the elegiac tradition in English poetry.

It seems that Goldsmith’s literary success was not accompanied by financial security. Fond of gambling and alcohol, Goldsmith was also generous with his money to others which meant that he was often in a pecuniary pickle. Most famously, his indigence helped bring about the publication of one of the most influential novels of the century: The Vicar of Wakefield (1766). As Samuel Johnson relates:

I received one morning a message from poor Goldsmith that he was in great distress, and, as it was not in his power to come to me, begging that I would come to him as soon as possible. I sent him a guinea, and promised to come to him directly, I accordingly went as soon as I was drest, and found that his landlady had arrested him for his rent, at which he was in a violent passion. I perceived that he had already changed my guinea, and had got a bottle of Madeira and a glass before him. I put the cork into the bottle, desired he would be calm, and began to talk to him of the means by which he might be extricated. He then told me that he had a novel ready for the press, which he produced to me. I looked into it, and saw its merit; told the landlady I should soon return, and having gone to a bookseller, sold it for sixty pounds. I brought Goldsmith the money, and he discharged his rent, not without rating his landlady in a high tone for having used him so ill. (Boswell, I, 416)

It is an engaging anecdote, and one that exposes the harsh reality of the eighteenth-century literary marketplace. Admittedly, the novel received a lukewarm reception on its publication—one biographer has speculated that perhaps only 2000 copies were sold in Goldsmith’s lifetime. However, after the author’s death, the novel was championed by a host of venerable writers including Walter Scott, Schlegel, Byron, Goethe, De Quincey, George Eliot, and William Thackeray. The great Goldsmith scholar Arthur Friedman has calculated that in the quarter century after Goldsmith’s death almost fifty editions of the novel were published in English as well as numerous editions in French and German. The novel remained a European phenomenon throughout the nineteenth century and has never been out of print.

Yet for all these achievements in poetry and prose fiction, for all his prodigious contribution to periodical culture in the mid-eighteenth century, it is Goldsmith’s dramatic work She Stoops to Conquer (1773) on which much of his modern reputation rests. This was his second play, his comedy The Good Natur’d Man having been performed at Covent Garden in 1768 with moderate success. She Stoops to Conquer is supposedly based on an embarrassing incident from Goldsmith’s early life in Ireland when he was tricked into thinking the house of a prominent landowner was an inn. Goldsmith barged in to demand his dinner and a bottle of wine, doubtless to the amused bafflement or indignation of the proprietor. He later decided that this was the stuff of stage comedy and began to write the play about 1771. Given the play’s continued vitality, it may seem extraordinary that there was initially considerable doubt over its success. Indeed, to achieve its production Samuel Johnson had to bring his considerable weight to bear on the theatre manager Colman. A contemporary playwright, Richard Cumberland, recalled: ‘Mr Colman, then manager of Covent Garden Theatre, protested against the comedy, when as yet he had not struck upon a name for it. Johnson at length stood forth in all his terrors as champion for the piece, and backed by us his clients and retainers demanded a fair trial’ (Mikhail 1993, 58). David Garrick—the most eminent actor of the day and manager of the rival Drury Lane—agreed to contribute a prologue, thus demonstrating a sort of patronage of the piece. Despite the support on the opening night of Johnson, Garrick, Edmund Burke, and other luminaries, Goldsmith himself was too apprehensive to attend the performance. Yet his misgivings were unnecessary – the play was a resounding success, a wonderful example of what Goldsmith himself called ‘laughing comedy’—a comedy that shifted away from the cloying sentimentalism of his antecedents. Goldsmith’s play included the depiction of ‘low’ characters (those from a lower socio-economic class), situations that bordered on the farcical, and shied away from explicit moralizing. ‘Laughing comedy’ was a comic mode that emphasized the entertainment of its audience, rather than their moral edification. The staging of She Stoops to Conquer by Smock Alley Theatre in 2012 to mark the reopening of Dublin’s Theatre Royal (opened 1662) marks its continuing appeal to audiences as well as its significance to Irish theatre history.

This brief survey of Goldsmith’s career does not do justice to his stature as a journalist and commentator in mid-eighteenth century London nor indeed as a historian (he was Professor of Ancient History for the Royal Academy). Despite his lack of personal charisma and conversational éclat, Goldsmith was one of the most respected men of letters of the day. His combined achievements in poetry, fiction, and drama of the eighteenth-century are difficult to surpass.

Cite as: ‘Oliver Goldsmith’ by David O’Shaughnessy at https://www.tcd.ie/trinitywriters. First published January 2016

Works Cited

- Bailey, Craig. Irish London: Middle-class Migration in the Global Eighteenth Century.Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013

- Boswell, James. Boswell’s Life of Johnson, ed. G.B. Hill, rev. and enl. L.F. Powell, 6volumes. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1934-64.

- Ginger, John. The Notable Man: The Life and Times of Oliver Goldsmith. London:Hamish Hamilton, 1977.

- Mikhail, E. H. (ed.). Goldsmith: Interviews and Recollections. Basingstoke: Macmillan,1993.

- Wardle, Ralph M. Oliver Goldsmith. Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press,1957.

Oliver Goldsmith after Sir Joshua Reynolds, oil on canvas (1769-1770) NPG 828. Creative Commons.

Oliver Goldsmith after Sir Joshua Reynolds, oil on canvas (1769-1770) NPG 828. Creative Commons.

John Henry Foley, Oliver Goldsmith, copper electrotype, Trinity College Dublin Art Collections. Reproduced by kind permission from the Board of Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin

John Henry Foley, Oliver Goldsmith, copper electrotype, Trinity College Dublin Art Collections. Reproduced by kind permission from the Board of Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin

Erected by public subscription initiated by the Earl of Carlisle, when Lord Lieutenant; unveiled and handed over to the College, who had contributed towards the cost, on 5 January 1864. John Henry Foley (1818-74) was a successful sculptor of monuments in Ireland, England, and India.

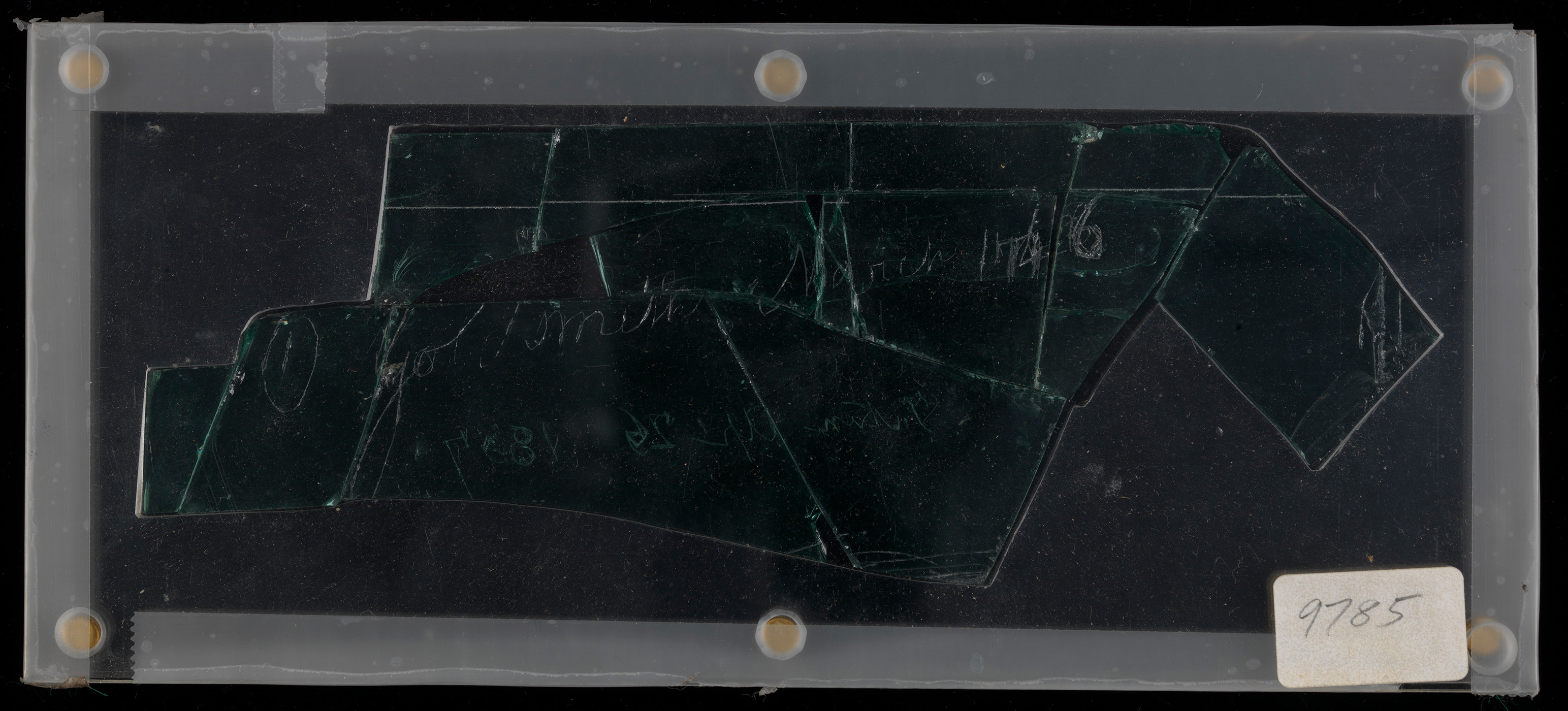

Signature of Goldsmith on glass (IE TCD MS 9785) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin

Signature of Goldsmith on glass (IE TCD MS 9785) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin

Although difficult to read, the inscription ‘O Goldsmith March 1746’ can just be made out; the autograph dates from Goldsmith’s student days

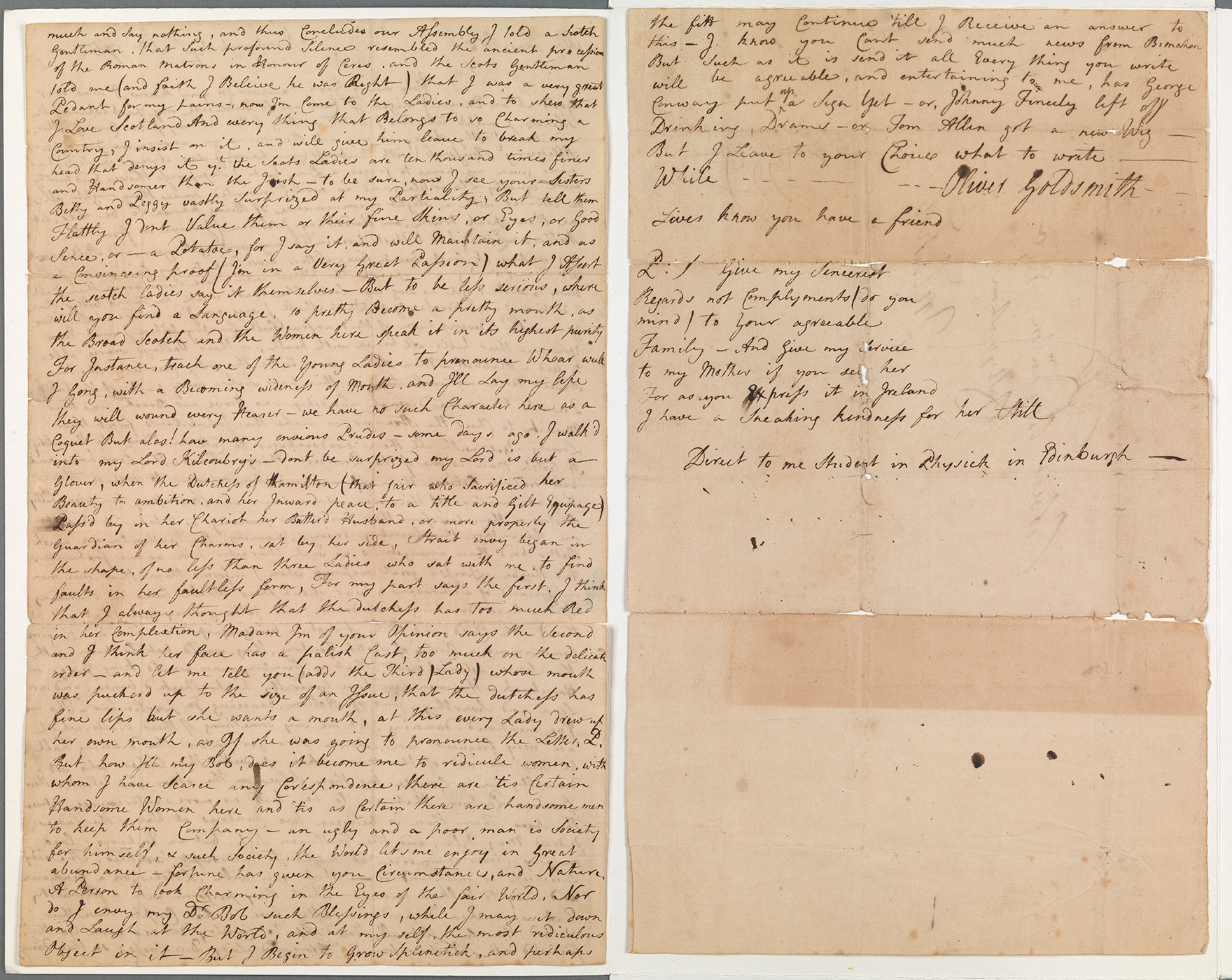

Excerpt from a letter from Oliver Goldsmith to Robert Bryanton, Esq., Ballymahon (TCD Deposit Goldsmith-Gregg Letter) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin

Excerpt from a letter from Oliver Goldsmith to Robert Bryanton, Esq., Ballymahon (TCD Deposit Goldsmith-Gregg Letter) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin

Written in 1753 when Goldsmith was a ‘Student in Physick’ in Edinburgh, this letter to his cousin and old College friend asks for news from home, but Goldsmith’s postscript suggests a family rift: ‘And Give my Service to my Mother if you see her for as you Express it in Ireland I have a Sneaking kindness for her still’.

The Deserted Village, a Poem (London: printed for W. Griffin, MDCCLXXV) (OLS X-1-20 no. 6) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin

The Deserted Village, a Poem (London: printed for W. Griffin, MDCCLXXV) (OLS X-1-20 no. 6) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin

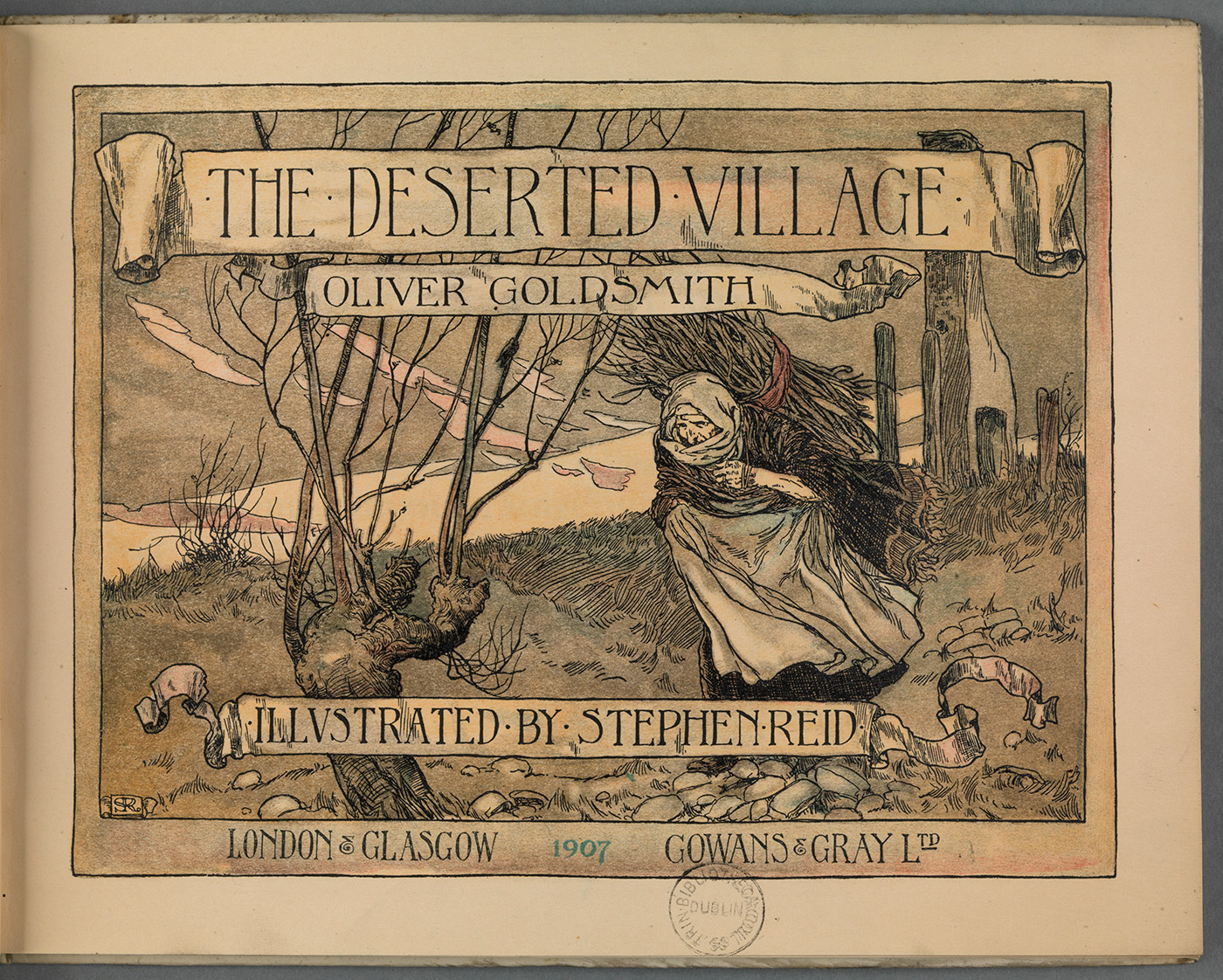

The Deserted Village illustrated by Stephen Reid (London and Glasgow: Gowans and Grey, 1907) (Gall: 20 g.72) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin

The Deserted Village illustrated by Stephen Reid (London and Glasgow: Gowans and Grey, 1907) (Gall: 20 g.72) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin

The Deserted Village illustrated by Stephen Reid (London and Glasgow: Gowans and Grey, 1907) (Gall: 20 g.72) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin

The Deserted Village illustrated by Stephen Reid (London and Glasgow: Gowans and Grey, 1907) (Gall: 20 g.72) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin

Goldsmith’s nostalgic view of ‘Sweet Auburn’ lent itself to idealized images of rural life, as here, in the early-twentieth century illustration of the village green by Stephen Reid

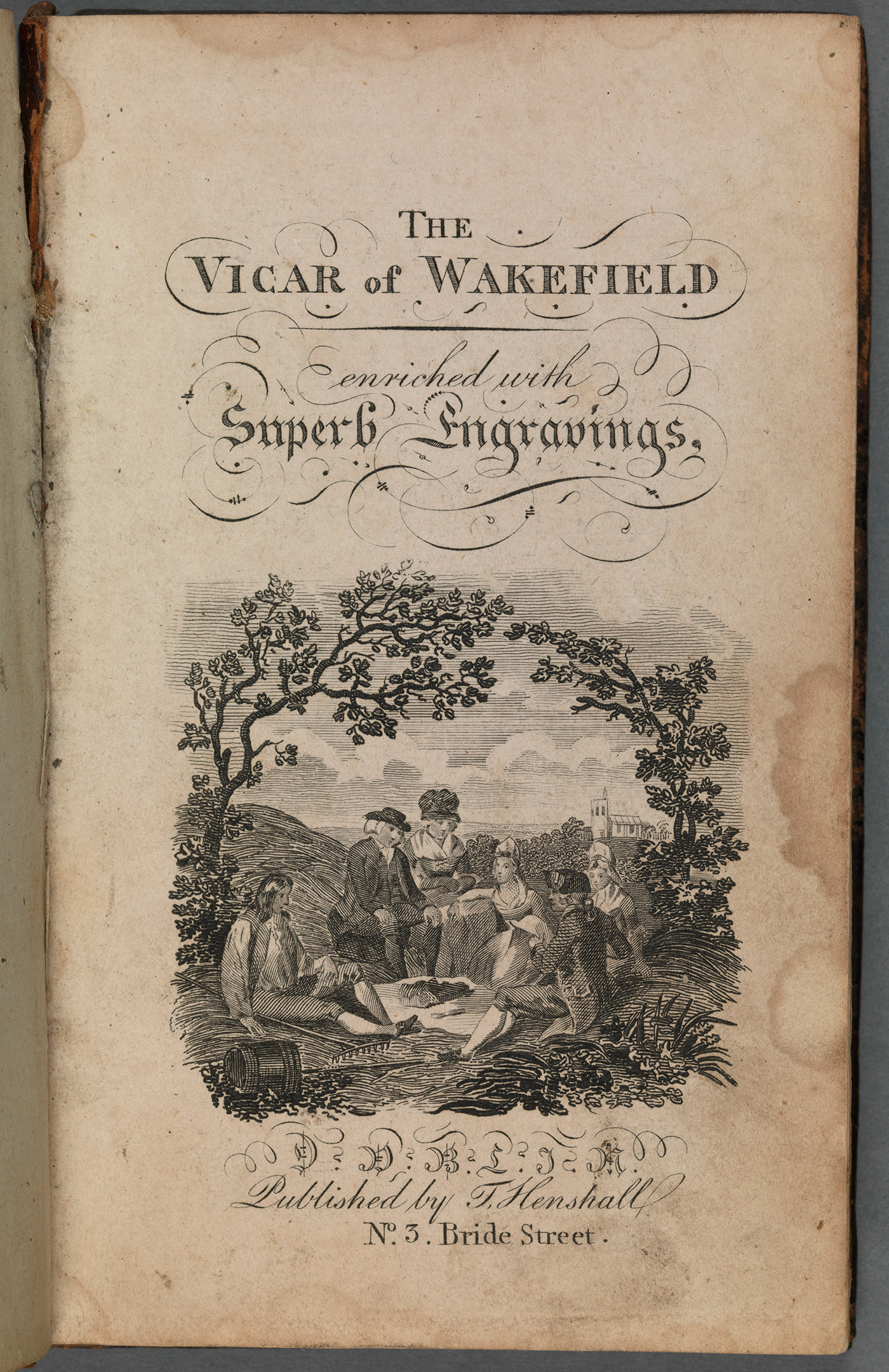

The Vicar of Wakefield (Dublin: T. Henshall, [1794]) (OLS B-11-206) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin

The Vicar of Wakefield (Dublin: T. Henshall, [1794]) (OLS B-11-206) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin

Since its publication in 1766 The Vicar of Wakefield has never been out of print and has proved attractive to many illustrators

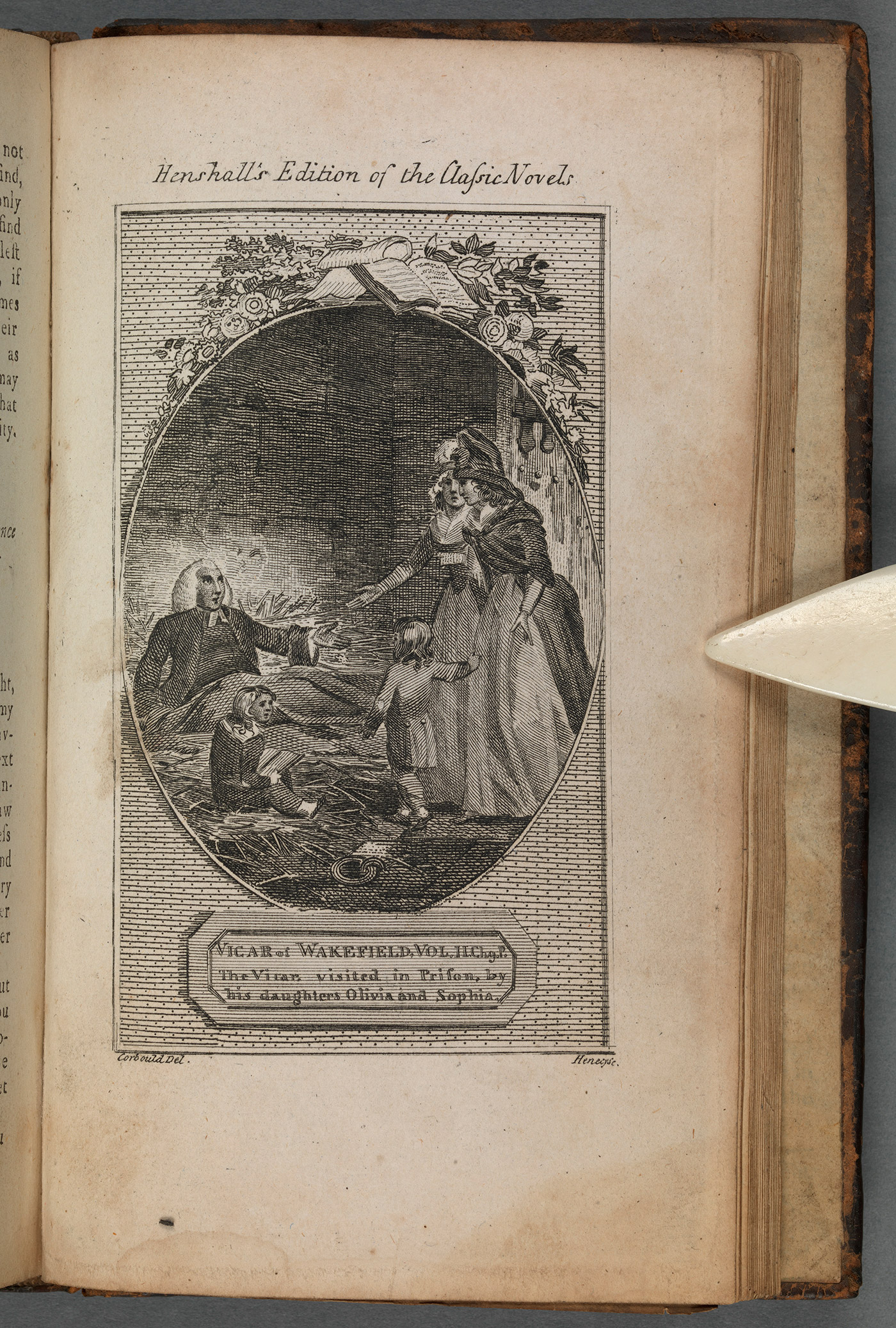

The Vicar of Wakefield (Dublin: T. Henshall, [1794]) (OLS B-11-206) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin

The Vicar of Wakefield (Dublin: T. Henshall, [1794]) (OLS B-11-206) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin

The episode in which Goldsmith’s Vicar is unjustly imprisoned, and makes successful attempts to better the lot of his fellow prisoners, was frequently excerpted and reprinted in the years immediately after the novel’s publication, and contributed to the movement for prison reform.

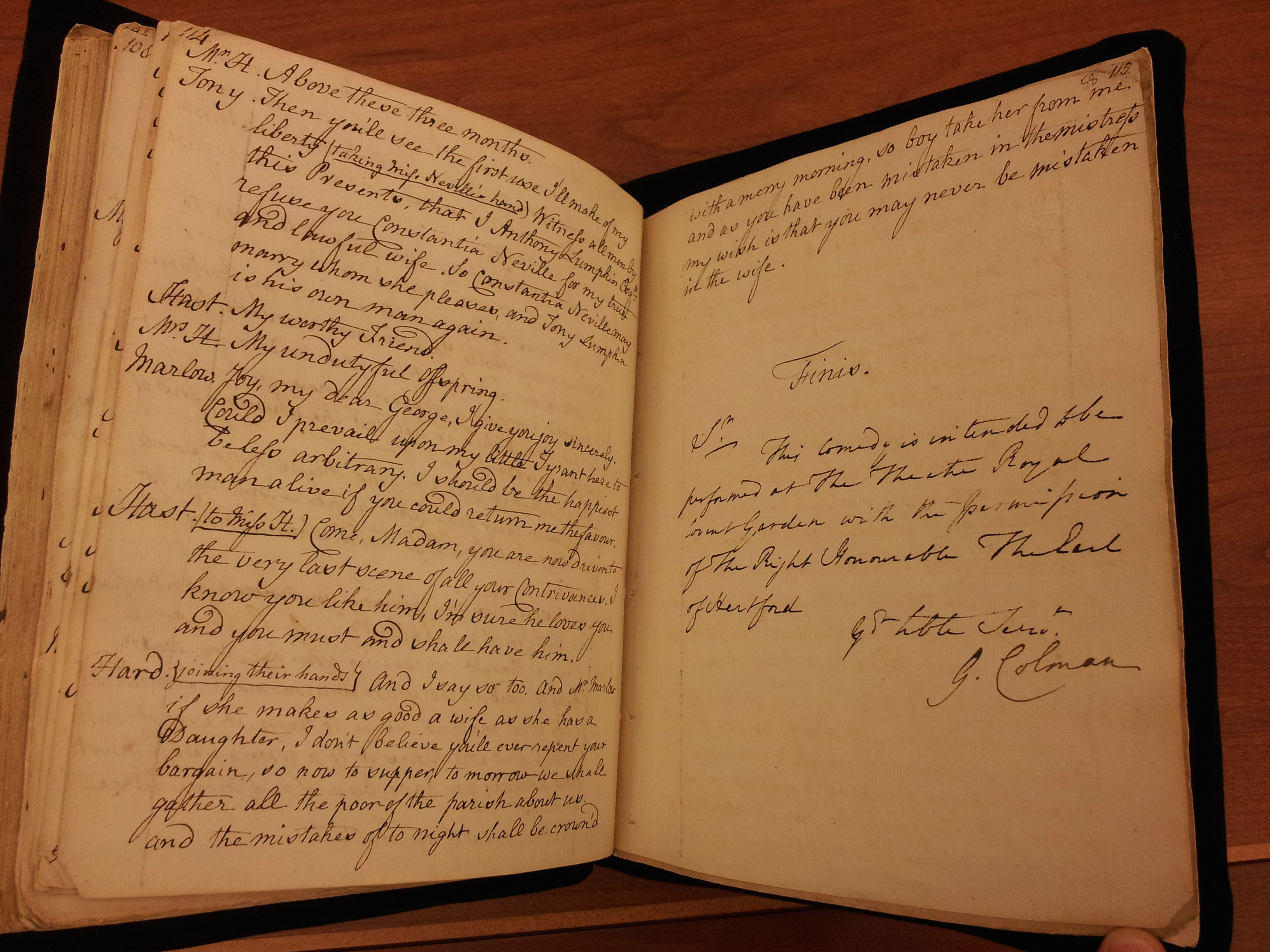

Manuscript of She Stoops to Conquer annotated by George Colman, theatre manager (Huntington Library, California, LA 349).

Manuscript of She Stoops to Conquer annotated by George Colman, theatre manager (Huntington Library, California, LA 349).

She Stoops to Conquer, first performed in 1773, has remained a vital play in the English dramatic repertoire and is regularly staged. Initially, George Colman, the theatre manager at Covent Garden, had to be convinced that the play was stageworthy.