Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin

Gerald Dawe

In her review of Paul Muldoon’s most recent poetry collection, One Thousand Things Worth Knowing (2015) Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin responds with a telling rebuttal to critics ‘who often focus on Muldoon’s talent for weirdness and his technical games’:

'It is hardly the main business of poetry to be normal, though this poetry turns out to be fit to take on the weight of normal life when called on.'

In many ways, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin could be reflecting upon her own poetry, particularly when she discusses the ‘pleasure’ Muldoon’s poetry gives: ‘It is language itself, its multiplicity and its straining after meaning that is illuminated by his work’. For what Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin and Paul Muldoon share is precisely this fascination with ‘language itself, its multiplicity and its straining after meaning’, set at times (though not necessarily so) within the parameters of ‘normal life’.

More often than not Ní Chuilleanáin’s poetry travels in time and location out of the here and now, crossing cultural borders of language and epochs to chart an imagined terrain unspecified and transcendent. This elusiveness produces an extraordinary shadow-land of suggested landscapes, hinted-at conversations, real and imagined journeys retold by a crystal clear poetic voice; once heard, never forgotten.

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin was born in Cork City in 1942, daughter of Professor Cormac O’ Chuilleanáin and the novelist Eilís Dillon. She was educated at University College Cork (BA in English & History 1962, MA 1964) and at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford (1964-66) before commencing her full-time academic career at Trinity College Dublin in 1966 where she lectured in medieval and renaissance English for forty five years up until her retirement as a Professor of English in 2011. Elected Fellow of the College (1993) her contributions to College life are extensive having been Head of the Department of English (1997-2000) and Dean of the Faculty of Arts-Letters (2001-05). Her distinguished contribution to mediaeval and renaissance studies has occasioned a festschrift, Enigma and Revelation in Renaissance English Literature: Essays Presented to Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin (2012), published to mark ‘the breadth as well as depth’ of Ní Chuilleanáin’s scholarship, that scholarship ‘notable for the effortless ease with which it has negotiated the often precarious balance between text and context and the clarity with which it has identified the general in the particular without compromising the historical specificity of the text’ (Cooney and Sweetnam, 9).

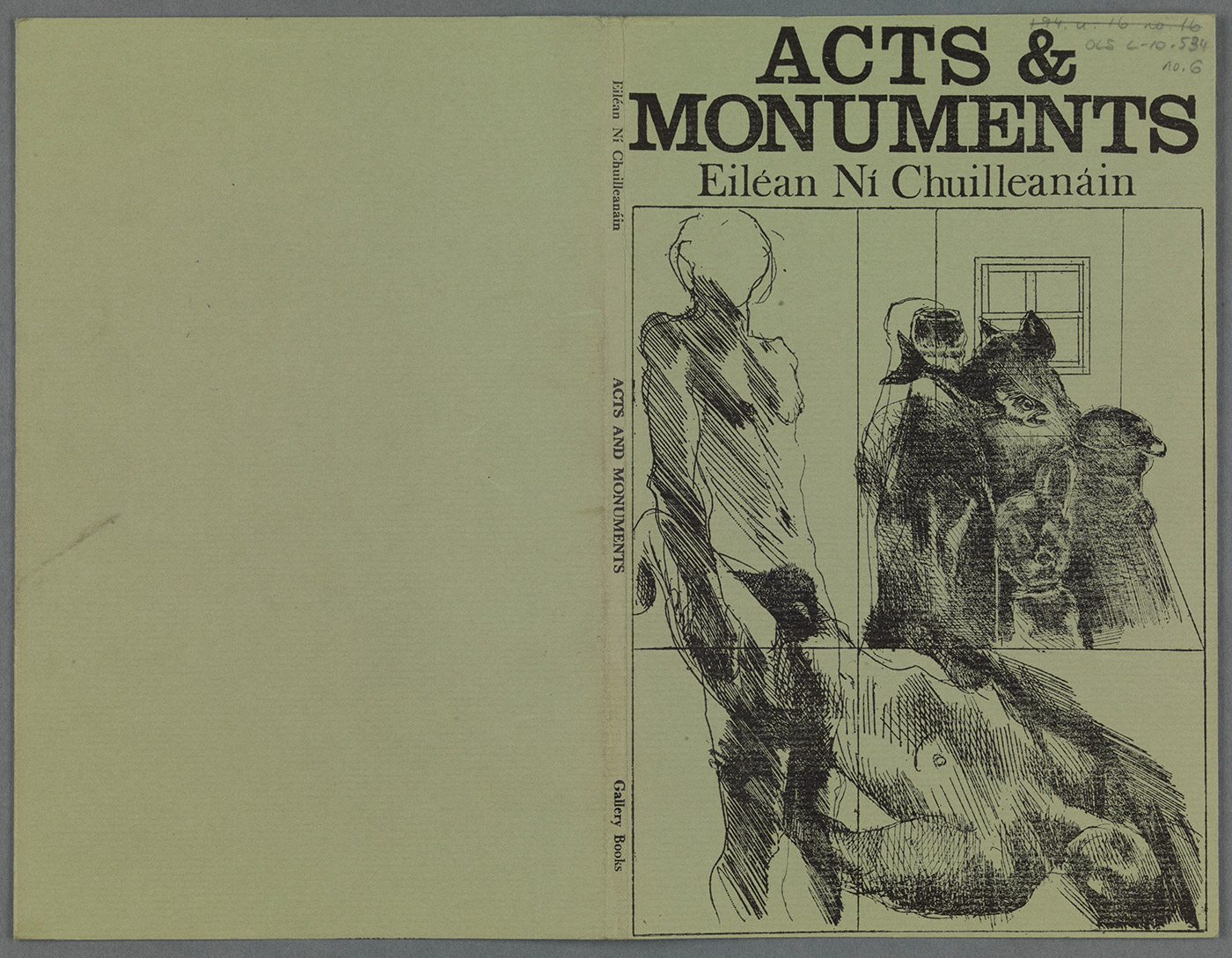

Depth, effortless ease, clarity and precarious balance are qualities which equally characterise Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin’s eight collections of poetry. From the initial volume Acts & Monuments (1972) to her most recent single collection, The Boys of Bluehill (2015), Ní Chuilleanáin’s verse has an unmistakable poise that seems at times on a cliff-edge between revelation and disappearance and loss. Her manifold imagination is drawn towards the light-filled landscapes of Italy — a central influence on her later volumes — and the intimacies of a local home, be that the recollected streets and houses of Cork or Dublin. This sense of quite literally moving from place to place, and translating one place or time into another, is a key to Ní Chuilleanáin’s poetry as a whole. It begins in ‘Home Town’:

The bus is late getting in to my home town.

I walk up the hill by the barracks,

Cutting through alleyways that jump at me.

They come bursting out of the walls

Just a minute before I began to feel them

Getting ready to arch and push. Here is the house.

(Selected Poems, 75)

Throughout these journeys in time and across different landscapes and languages, Ní Chuilleanáin characteristically establishes representative lives of family and friends, often women (for example, Katherine Kavanagh, the wife of the poet, Agnes Bernelle, actress and singer, and Leland Bardwell, writer) to carry the emotional significance of what is not being said, such as in the elegy, ‘At My Aunt Blánaid’s Cremation’:

But your face looks away now,

And we on your behalf

Recall how lights and voices

And bottles and wake glasses

Were lined up like the cousins

In a bleached photograph.

(Selected Poems, 116)

The commemorated experience of religious life is similarly figured in poems to Saint Margaret of Cortona, the Anchoress and the Magdalenes, among several other poems which present a complicated picture of female sexuality, institutional power and how women find themselves often isolated from a living and embracing community. It is a point Aingeal Clare emphasised in her Guardian review of The Boys of Bluehill:

The collective noun for nuns is a “murmur”, which captures wonderfully the secret histories that echo through Ní Chuilleanáin’s work, not to mention the ubiquity of nuns in her poems . . . Among the attractions of nuns for Ní Chuilleanáin is the cloistered social space they occupy[.]

So do apparitions, litanies, and a host of pilgrims bring the reader into a deeper sense of wondering otherness.

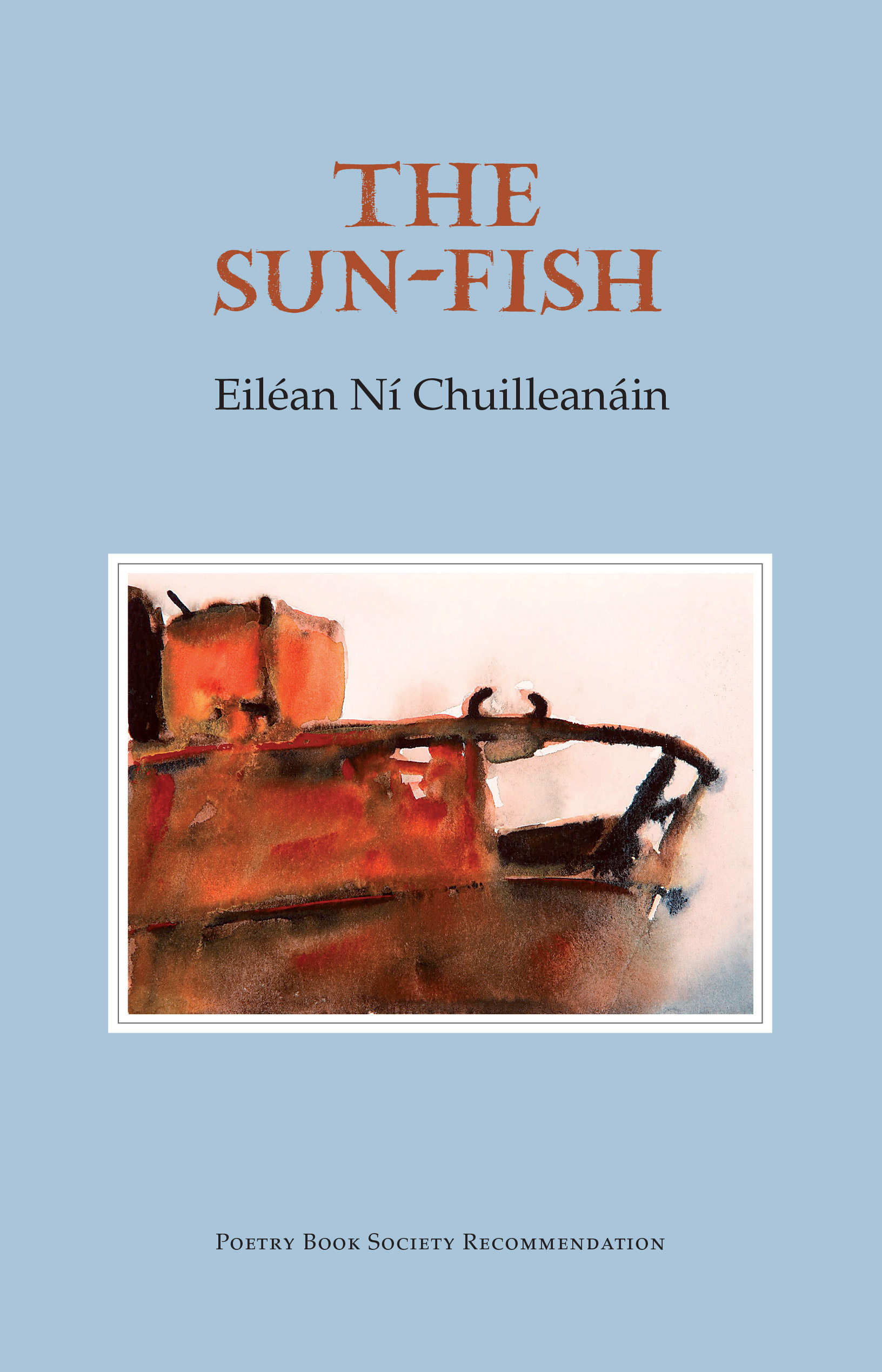

The atmospherics of Ní Chuilleanáin’s individual collections merge a spiritual world with the everyday particulars of looking out a kitchen window; sensing animal life stirring in the countryside; negotiating imaginatively the seas as in the splendid sequence of four poems ‘The Sun-Fish’ (glossed as ‘Basking shark, An Liamhán Gréine, Cetorhinus maximus’) which opens with ‘The Watcher’:

The salmon-nets flung wide, their drifted floats

Curve, ending below the watcher’s downward view

From the high promontory. A fin a fluke

And they are there, the huge sun-fish,

Holding still, stencilled in the shallows.

The sense of the spectacular nestles under the surface of the poem ‘stencilled in the shallows’ but also under the surface of so much of Ní Chuilleanáin’s verse. Seamus Heaney’s remark, quoted in Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin’s essential Selected Poems (2008), captures this magical seeing:

There is something second-sighted…about Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin’s work, by which I don’t mean that she has any prophetic afflatus, more that her poems see things anew, in a rinsed and dreamstruck light. They are at once as plain as an anecdote told on the doorstep and as haunting as a soothsayer’s greeting.

It is a balance explored in detail in recent publications dedicated to Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin’s achievement as poet and translator, primarily from Irish, Italian and Romanian. A special issue of the Irish University Review edited by Anne Fogarty is a good place to start along with Guinn Batten’s fine essay in The Cambridge Companion to Contemporary Irish Poetry (2003). Justin Quinn’s lucid and contextualising study, The Cambridge Introduction to Modern Irish Poetry (2008) identifies the cosmopolitan and European roots of Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin and her contemporaries while Patricia Boyle Haberstroh has published a pioneering study of The Female Figure in Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin’s Poetry (2013).

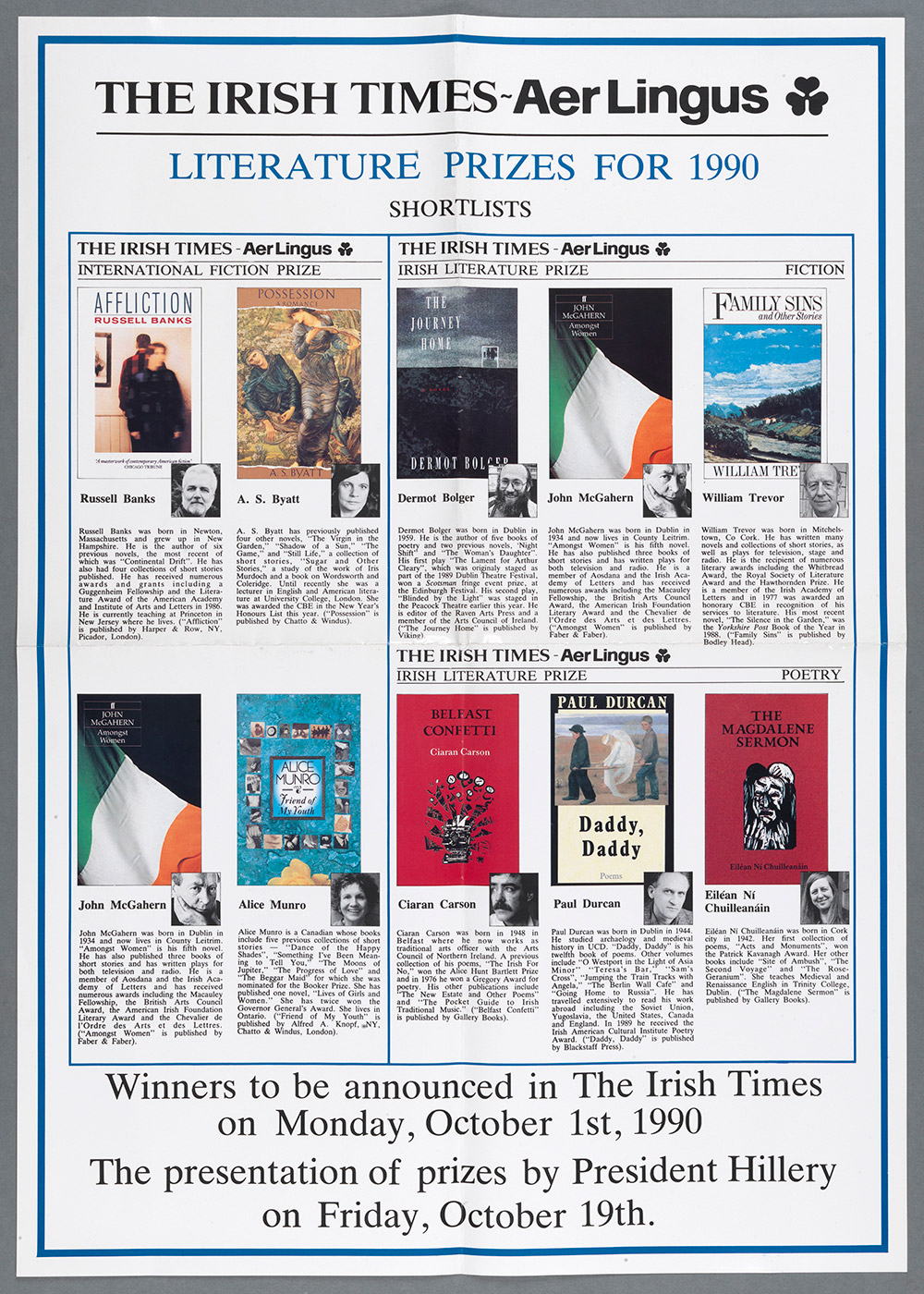

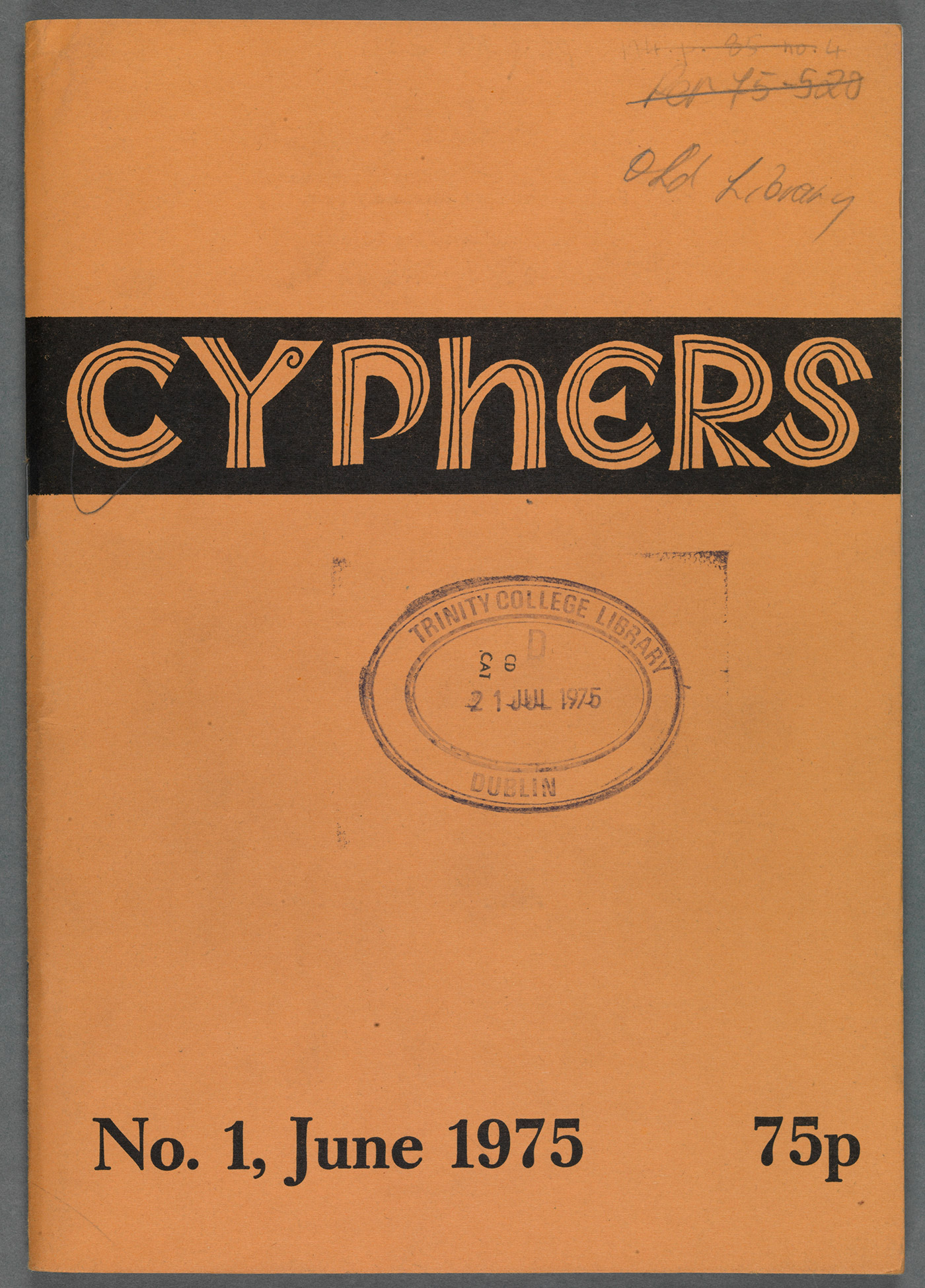

Recipient of several important honours since The Irish Times prize for poetry in 1966, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin’s The Sun-Fish was awarded the prestigious Griffin International Poetry Prize in 2010. She is a member of Aosdána, the assembly of Irish artists, and is one of the founding editors of Cyphers (1975), the long-established Irish literary journal which has done so much to bring younger and less established names to a wider audience as well as critically maintaining connection to an older generation of poets and prose writers including Pearse Hutchinson and Dermot Healy.

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin’s other writing includes a fascinating range of engagements with various literary and social issues. She edited the pioneering anthology, Irish Women: Image and Achievement: Women in Irish Culture from earliest times (1985); As I was Among the Captives: The Prison Diary of Joseph Campbell, 1922-23 (2001); and The Wilde Legacy (2003), based upon the international symposium held at Trinity College to mark the opening of The Oscar Wilde Centre in the School of English. Her work as a translator—from Irish, Italian, and Romanian—is also a central part of her writing life. With Medbh McGuckian, she has translated poems from the Irish by Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill in The Water Horse (1999); with Cormac Ó’Cuilleanáin and Gabriel Rosenstock, she has translatedfrom the Italian of Michele Ranchetti in Verbale/Minutes/Tuairisc (2002). After the Raising of Lazarus, poems by Ileana Mălăncioiu translated from the Romanian by Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, appeared in 2005.

In one of her finest poems, ‘Studying the Language’, a chastening re-invention of the solitude of poetry-making, as much as a depiction of the hermetic life, Ní Chuilleanáin seems to have disappeared into language itself, a remarkable ego-less act of self-belief and conviction in the power of scene and inference to set up in the reader’s mind an emblematic meaning, as mysterious as the poem’s setting:

On Sundays I watch the hermits coming out of their holes

Into the light. Their cliff is as full as a hive.

They crowd together on warm shoulders of rock

Where the sun has been shining, their joints crackle.

They begin to talk after a while.

I listen to their accents, they are not all

From this island, not all old,

Not even, I think, all masculine.

They are so wise, they do not pretend to see me.

They drink from the scattered pools of melted snow:

I walk right by them and drink when they have done.

I can see the marks of chains around their feet.

I call this work, these decades and stations —

Because, without these, I would be a stranger here.

(Selected Poems, 89)

The taut sentences, though almost ghostly, mask the poem’s inner legacy to a Gaelic idiom as if in translation from a previously imagined world view of which we are afforded just a glimpse — of ‘these decades and stations’ which belong to another time. ‘An Information’, which opens Ní Chuilleanáin’s most recent volume, The Boys of Bluehill (2015) is also a poem of re-visitation but on this occasion the journey back is more immediate and identifiable:

I returned to that narrow street

where I used to stand and listen

to the chat from the kitchen or parlour, filtered

through rotten tiles. I thought

the rough walls seemed higher than before.

My cheek against the stone, I noted the new door

Since last I’d been here, began to count the years,

to count the questions I couldn’t ask now

(The Boys of Bluehill, 11)

The conversational tone, the casual flow of mid- to end-half rhymes (parlour, higher, before, door, there, years; tiles, walls; street, chat, count) seems almost overlooked as the poem conveys its displaced yet clarifying sense of reality. The recollection and the present co-exist, to quote the poem’s concluding lines, ‘where’ reality is ‘hidden again when found’. The bounty of life ‘outdoors’, and lived, makes The Boys of Bluehill a collection full of nature. But the collection is probably most noted for its sense of the past being present in unexpected ways, random occurrences, and journeys taken.

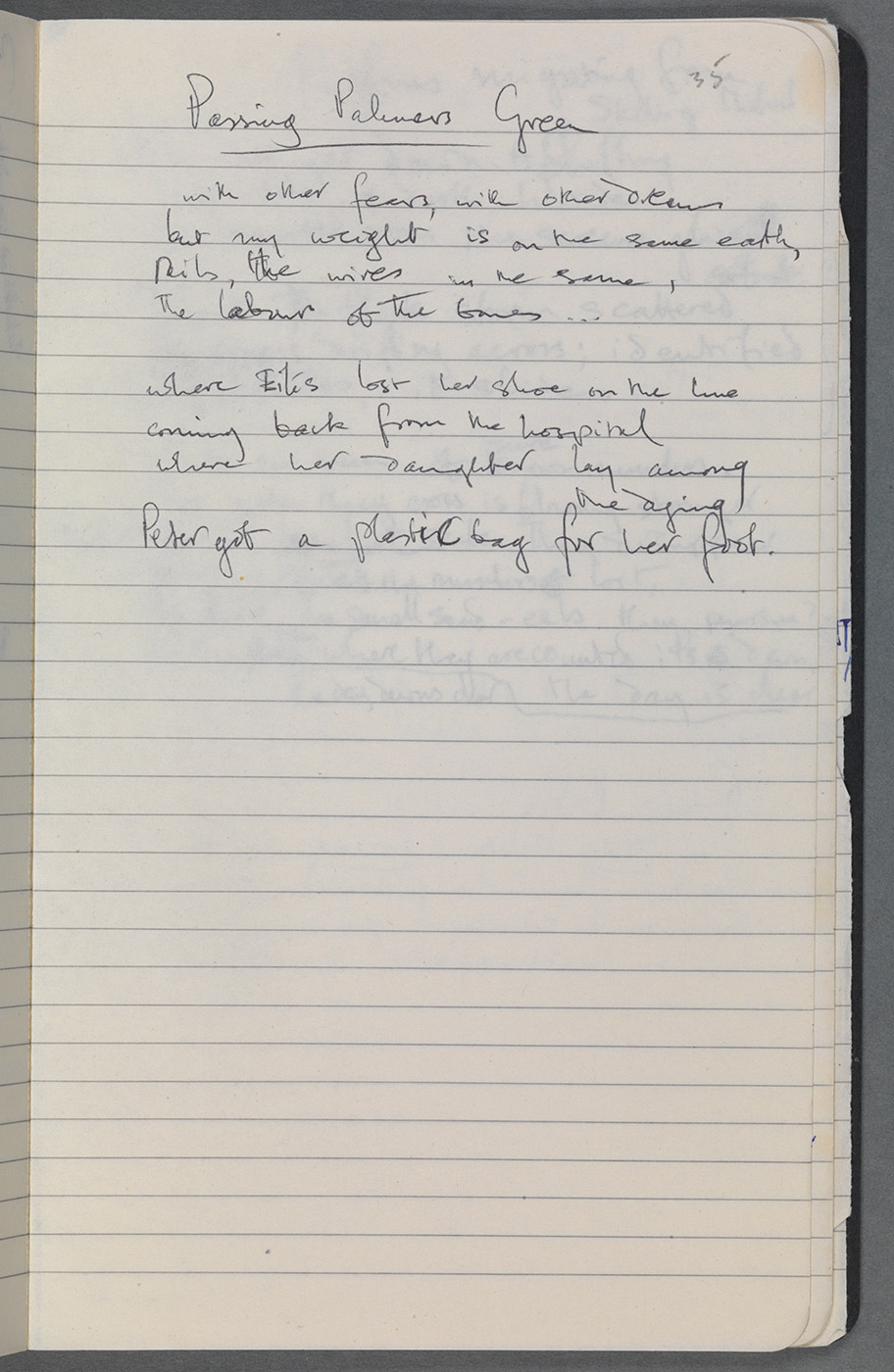

Ní Chuilleanáin’s poetry, without any sign of self-regarding anxiety, carries an authority all by itself and there is little sense of questions over where we are to ‘place’ the poet or her findings. Her poetry is at ease and confident with being in the world — of languages learned and used, of literatures read and absorbed, of cultures experienced over time and of family life with its joys (marriages, births) and anguishes (deaths of loved ones) such as one finds in The Boys of Bluehill. In the pitch-perfect quasi-sonnet, ‘Passing Palmers Green Station’ which recounts a journey on the London Underground that brings back to the poet’s mind an earlier journey with her mother to visit ‘her younger daughter/among the dying’ the transposition of the concluding two lines is both heart-breaking and releasing:

The train dips

under the ground, and for the last stage

of this journey I am close to them, to the gap

that resembles the dark side of the moon in Ariosto,

where Astolfo flew on the hippogriff, and discovered

that everything lost on the earth can again be found.

(The Boys of Bluehill, 54)

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin’s powers of suggestion can take us on a simple journey on the London Underground yet it one that also, naturally enough, includes the legendary winged horse with eagle’s body, the hippogriff and the magical world of Ludovico Ariosto, the sixteenth century Italian poet. She is one of the very few poets writing today who can make us believe that not only is this possible but that, also, more importantly as the poem implies, nothing is ever ‘lost’.

Cite as: ‘Eilean Ní Chuilleanáin’ by Gerald Dawe at https://www.tcd.ie/trinitywriters. First published January 2016.

Works Cited

- Clare, Aingeal, http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/may/29/the-boys-of-bluehill-eilean-ni-chuilleanain-review

- Cooney, Helen, and Sweetnam, Mark, eds. Enigma and Revelation in Renaissance English Literature: Essays Presented to Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2012.

- Ní Chuilleanáin, Eiléan. Acts & Monuments. Dublin: Gallery Press, 1972.------.

------, ed. Irish Women: Image and Achievement: Women in Irish culture from ancient times. Dublin: Arlen House, 1985.

------, ed. As I was Among the Captives: The Prison Diary of Joseph Campbell, 1922-23. Cork: Cork University Press, 2001.

------, ed. The Wilde Legacy. Dublin: Four Courts Press 2003.

------. Selected Poems. Oldcastle, Co. Meath: Gallery Press, 2008; London: Faberand Faber 2008.

------. The Sun-Fish. Oldcastle, Co. Meath: Gallery Press, 2009.

------. ‘Rousing the Reader: One Thousand Things Worth Knowing by Paul Muldoon’. Dublin Review of Books (Issue 66, April 2015) http://www.drb.ie/essays/rousing-the-reader

------. The Boys of Bluehill. Oldcastle Co.Meath: Gallery Press 2015.

------. Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, The Water Horse with translations into English byEiléan Ní Chuilleanáin and Medbh McGuckian. Oldcastle, Co. Meath: Gallery Press 1999.

------. Verbale/Minutes/Tuairisc/ from the Italian of Michele Ranchetti with Cormac O Chuilleanáin and Gabriel Rosenstock. Dublin: Institito Italiano di Cultura 2002.

Further Reading

- Batten, Guinn. ‘Boland, McGuckian, Ní Chuilleanáin and the body of the nation’, in The Cambridge Companion to Contemporary Irish Poetry, ed. Matthew Campbell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Fogarty, Anne, ed. ‘Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin: Special Issue’, Irish University Review: A Journal of Irish Studies. Spring/Summer 2007.

- Haberstroh, Patricia Boyle. The Female Figure in Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin’s Poetry. Cork: Cork University Press, 2013.

- Quinn, Justin, The Cambridge Introduction to Modern Irish Poetry 1800-2000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Photograph by Brian McGovern courtesy of The Gallery Press

Photograph by Brian McGovern courtesy of The Gallery Press

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Acts and Monuments (Gallery Books, 1972) (OLS-L-10-534-no.6) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Acts and Monuments (Gallery Books, 1972) (OLS-L-10-534-no.6) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin

An Múinteoir: The Irish Teachers’ Journal, 2:3 (1988) (TCD MS11404) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin

An Múinteoir: The Irish Teachers’ Journal, 2:3 (1988) (TCD MS11404) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, The Sun-Fish (2009). Image courtesy of The Gallery Press

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, The Sun-Fish (2009). Image courtesy of The Gallery Press

The Sun-Fish was awarded the Griffin International Poetry Prize in 2010

Poster of shortlisted works for the Irish Times-Aer Lingus literature prizes, 1990. (TCD MS11404) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin

Poster of shortlisted works for the Irish Times-Aer Lingus literature prizes, 1990. (TCD MS11404) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin

Cyphers 1 (1975) (OLS Per-4) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Cyphers 1 (1975) (OLS Per-4) by permission of the Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Along with Leland Bardwell, Pearse Hutchinson, and Macdara Woods, Eiléan Ni Chuilleanáin was a founding editor of Cyphers, founded in 1975 and one of Ireland’s longest-established literary magazines.

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Legend of the Walled-Up Wife: Translations from the Romanian of Ileana Mălăncioiu (2011). Image courtesy of The Gallery Press

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Legend of the Walled-Up Wife: Translations from the Romanian of Ileana Mălăncioiu (2011). Image courtesy of The Gallery Press

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, The Boys of Bluehill (2015). Image courtesy of The Gallery Press

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, The Boys of Bluehill (2015). Image courtesy of The Gallery Press

Manuscript version of ‘Passing Palmers Green’ (TCD MS11404) by permission of the author and the Board of Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin

Manuscript version of ‘Passing Palmers Green’ (TCD MS11404) by permission of the author and the Board of Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin