For the 2020 election, click here.

For material on Ireland's 2007 election, click here. For results of the 2019 European Parliament elections in Ireland, click here. For information on results of Irish elections 1948 to 2007, click here. For information on results of Irish elections 1922 to 1944, including the exceptional election of June 1927, click here. For arguments for and against retaining PR-STV as Ireland's electoral system click here.

This page was created and continuously updated during the 2011 election campaign. After the initial section covering the results, it has been left largely as it stood on election day, 25 February, with occasional post-election comments added. For result of Presidential election 2011, scroll about a quarter of the way down this page.

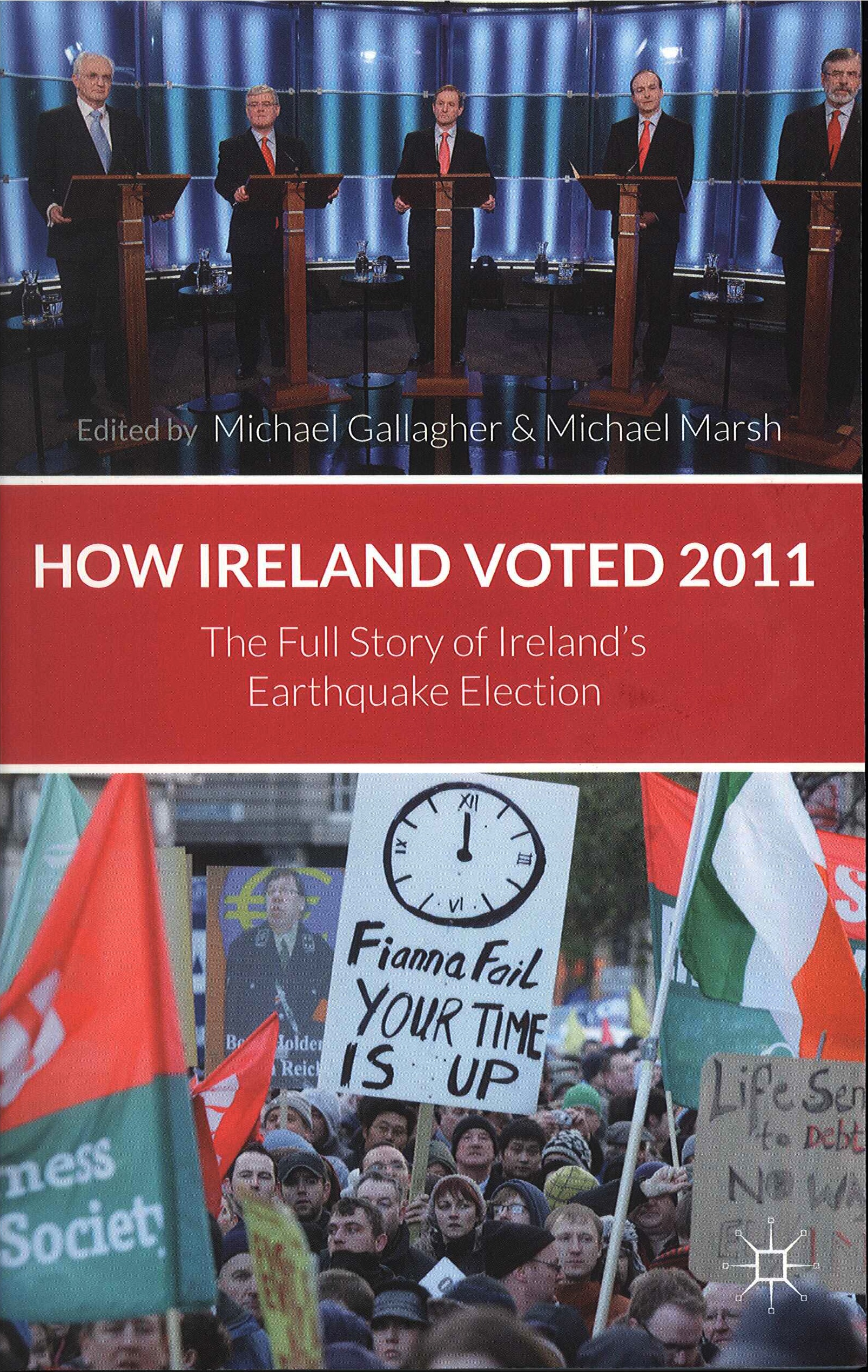

The results of the election justified the tag 'earthquake election'. This is incorporated into the subtitle of How Ireland Voted 2011, published by Palgrave Macmillan in October 2011.

On Tuesday 1 February 2011 the President of Ireland, Mary McAleese, acting on the advice of the Taoiseach (prime minister), Brian Cowen, dissolved the 30th Dáil. The 31st Dáil was elected on Friday 25 February; polling stations were open from 7 am to 10 pm. Nominations of candidates closed at noon on Wednesday 9 February. The number of candidates, at 566, was a record (see 'Candidates' and 'Records' sections below).

The 166 TDs (members of the Dáil) were elected from 43 constituencies by means of the PR-STV electoral system (see ballot paper); one, the outgoing Ceann Comhairle (chair of the Dáil), was deemed elected without a contest (Séamus Kirk in Louth), leaving 165 seats to be contested. These 165 TDs were returned from 17 3-seat constituencies, 16 4-seat constituencies, and 10 5-seat constituencies. Once voting finished, the ballot boxes were sealed and were then brought overnight to a central counting point within each constituency. Checking and counting of the votes began at around 9 am on Saturday 26 February, and the first member of the 31st Dáil, Joan Burton in Dublin West, was elected at around 2.45 pm on that day. Because the counting of votes under PR-STV is a multi-stage process, the final results of the election were not known until a little after 8 am on Wednesday 2 March when, after some recounts, Seán Kyne (FG) was elected to the final seat in Galway West, though most constituencies completed their counting on Saturday 26 February.

The Dáil met first on Wednesday 9 March. Having elected a new Ceann Comhairle, Seán Barrett (FG, Dun Laoghaire), it proceeded to elect Enda Kenny as Taoiseach, and it then approved his nomination of ministers as members of the Fine Gael–Labour coalition government.

Results 2011

The results of the Dáil election 2011 are fully analysed in How Ireland Voted 2011 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). The raw figures are:

| 2011 election result | Candidates |

Votes |

% vote |

Change since 2007 |

Seats |

Change since 2007 |

% seats |

|

| Fine Gael | 104 |

801,628 |

36.10 |

+8.78 |

76 |

+25 |

46.06 |

|

| Labour | 68 |

431,796 |

19.45 |

+9.32 |

37 |

+17 |

22.42 |

|

| Fianna Fáil | 75 |

387,358 |

17.45 |

-24.11 |

19 |

-58 |

11.52 |

|

| Sinn Féin | 41 |

220,661 |

9.94 |

+3.00 |

14 |

+10 |

8.48 |

|

| United Left Alliance | 20 |

59,423 |

2.68 |

+1.59 |

5 |

+5 |

3.03 |

|

*Socialist Party |

9 |

26,770 |

1.21 |

+0.57 |

2 |

+2 |

1.21 |

|

*People before Profit |

9 |

21,551 |

0.97 |

+0.52 |

2 |

+2 |

1.21 |

|

*Other ULA |

2 |

11,102 |

0.50 |

+0.50 |

1 |

+1 |

0.61 |

|

| Green Party | 43 |

41,039 |

1.85 |

-2.84 |

0 |

-6 |

0 |

|

| Workers Party | 6 |

3,056 |

0.14 |

-0.01 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

| Christian Solidarity Party | 8 |

2,102 |

0.09 |

+0.01 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

| People's Convention | 4 |

1,512 |

0.07 |

+0.07 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

| Fís Nua | 5 |

938 |

0.04 |

+0.04 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

| Direct Democracy Ireland | 3 |

588 |

0.03 |

+0.03 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

| Progressive Democrats | 0 |

0 |

0 |

-2.73 |

0 |

-2 |

0 |

|

| Independents | 189 |

270,258 |

12.17 |

+7.00 |

14 |

+9 |

8.48 |

|

| Total | 566 |

2,220,359 |

100.00 |

0 |

165 |

0 |

100.00 |

* Part of United Left Alliance, which did not exist as such in 2007.

Notes:

(i) derived from official sources. However, these classify Kevin McCaughey, a candidate in Cork South-West who received 765 first preferences, as an Independent, whereas all other sources classify him as a Green Party candidate, he was listed on the Notice of Poll as a Green Party candidate, and he is included on the Green Party website as a Green Party candidate, so he is treated in the table above as a Green Party candidate;

(ii) Table refers to contested seats; FF also won the one uncontested seat (automatic re-election of Ceann Comhairle in the Louth constituency), giving it 20 seats out of 166 in the 31st Dáil;

(iii) 20 independent candidates were loosely linked in an alliance called New Vision. New Vision was not a party, let alone a registered party, describing itself as 'an association of independent candidates, working together to change the way we 'do' politics in Ireland'. Together they won 25,422 votes, and one of these candidates was elected. This candidate, Luke 'Ming' Flanagan in Roscommon–South Leitrim, was and is in practice regarded as an independent rather than as in any sense a representative of New Vision;

(iv) The 'People's Convention', also not registered, ran 4 candidates in three constituencies in Cork;

(v) Direct Democracy Ireland, also not registered, ran three candidates in Dublin;

(vi) The Progressive Democrats, a party that had contested the 2007 election, had ceased to exist by the time of the 2011 election.

Electorate: 3,209,244. Turnout (valid vote / electorate): 69.19% (+2.79 compared with 2007). Invalid votes 22,817.

| Election indices | |

| Disproportionality (least squares index) | 8.69 |

| Effective number of elective parties (Nv) | 4.77 |

| Effective number of legislative parties (Ns) | 3.52 |

Note: figures based on complete disaggregation of Others, with each of the 189 independent candidates and 14 independent TDs treated as a separate unit.

If seats were allocated purely on the basis of total national first preference votes, and if all votes had been cast as they were on 25 February, then the allocation of the 165 seats under the Sainte-Laguë method (generally seen as the 'fairest' since it does not systematically favour either larger or smaller parties) would have been FG 64, Lab 35, FF 31, SF 18, ULA 5, Greens 3, Independents 9 (Shane Ross 1, Michael Lowry 1, Mick Wallace 1, Luke 'Ming' Flanagan 1, Catherine Murphy 1, Michael Healy-Rae 1, Stephen Donnelly 1, James Breen 1, Tom Fleming 1). Under the D'Hondt method, which tends to give the benefit of the doubt to larger parties, the figures would have been FG 68, Lab 36, FF 32, SF 18, ULA 5, Greens 3, Independents 3 (Shane Ross 1, Michael Lowry 1, Mick Wallace 1).

There was an increase in the number of female TDs, though only a small one: from 22 in 2007 to 25 in 2011. With only 15.1 per cent of TDs being female, Ireland continues to occupy a low position in the international league table for gender balance within parliament. Of the 23 women who were members of the 30th Dáil at the time of its dissolution, 6 retired, and 8 were defeated. The other 9 were re-elected, and in addition 14 new female TDs were elected, along with a further 2 who had had a previous spell as a TD and were now returning to the Dáil. For discussion of women and politics, see the CAWP site.

Candidates |

Votes |

% vote |

Change since 2007 |

Seats |

Change since 2007 |

% seats |

||

| Men | 480 |

1,870,315 |

84.23 |

-0.40 |

140 |

-3 |

84.85 |

|

| Women | 86 |

350,044 |

15.77 |

+0.40 |

25 |

+3 |

15.15 |

|

| Total | 566 |

2,220,359 |

100.00 |

0 |

165 |

0 |

100.00 |

Note: the 166th TD, returned without a contest, is male.

Incumbents fared better pro rata than non-incumbents, but, unusually, a majority of those elected were not incumbents:

| 2011 | Candidates |

Votes |

% vote |

Seats |

% seats |

|

| Incumbent TDs | 126 |

942,228 |

42.44 |

81 |

49.09 |

|

| Other candidates | 440 |

1,278,131 |

57.56 |

84 |

51.91 |

|

| Elected candidates | 165 |

1,375,846 |

61.97 |

165 |

100.00 |

|

| Unsucccessful candidates | 401 |

844,513 |

38.03 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

| Total | 566 |

2,220,359 |

100.00 |

165 |

100.00 |

________________________

Presidential election 27 October 2011

| Candidate | Party | First preference votes |

% first preference votes |

After Count 2 |

After Count 3 |

After Count 4 |

| Michael D. Higgins | Labour | 701,101 |

39.57 |

730,480 |

793,128 |

1,007,104 |

| Seán Gallagher | Independent | 504,964 |

28.50 |

529,401 |

548,373 |

628,114 |

| Martin McGuinness | Sinn Féin | 243,030 |

13.72 |

252,611 |

265,196 |

|

| Gay Mitchell | Fine Gael | 113,321 |

6.40 |

127,357 |

136,309 |

|

| David Norris | Independent | 109,469 |

6.18 |

116,526 |

||

| Dana Rosemary Scallon | Independent | 51,220 |

2.89 |

|||

| Mary Davis | Independent | 48,657 |

2.75 |

|||

| Non-transferable | 15,387 |

28,756 |

136,544 |

|||

| Total | 1,771,762 |

100.00 |

1,771,762 |

1,771,762 |

1,771,762 |

Electorate: 3,191,157

Valid votes: 1,771,762

Turnout (valid votes / electorate): 55.52 per cent

________________________

Running commentary on the election campaign, as well as on other subjects, can be found at the Political Reform site. The ElectionsIreland site maintained by Seán Donnelly and Christopher Took also has a huge amount of useful information. Elections are organised by the Department of the Environment, but from its elections web page (which is difficult to find in the first place) one would hardly know that an election is taking place. Noel Whelan's up-to-the-minute book The Tallyman's Campaign Handbook: Election 2011 (Dublin: Liberties Press), launched on 15 February, has in-depth information on the candidates in every constituency and much more besides.

The 31st Dáil will convene on Wednesday 9 March. It will first elect its Ceann Comhairle, and will then elect a Taoiseach, the 13th prime minister of the independent Irish state. He (the election of the first female Taoiseach is still some way off) will put forward the names of ministers, whose nomination must be approved by the Dáil.

When will the result be known?

The 166 TDs (members of the Dáil) are elected from 43 constituencies by means of the PR-STV electoral system (see ballot paper). One, the outgoing Ceann Comhairle (chairperson of the Dáil), on this occasion Séamus Kirk (FF) in the Louth constituency, is deemed elected without a contest, leaving 165 seats to be contested. These 165 TDs are returned from 17 3-seat constituencies, 16 4-seat constituencies, and 10 5-seat constituencies. Once voting finishes, the ballot boxes are sealed and will then be brought overnight to a central counting point within each constituency. Checking and counting of the votes will begin at around 9 am on Saturday 26 February. On the basis of the 2007 pattern, the first member of the 31st Dáil may be elected at around 2 pm on that day. Because the counting of votes under PR-STV is a multi-stage process, the final results of the election are unlikely to be known until the evening, or even late on the night, of Sunday 27 February, though most constituencies will complete their counting on Saturday 26th. The fact that there are almost 100 more candidates in 2011 than there were in 2007 may mean that counting the votes takes longer than it did then.

It may be clear by Saturday evening that the only possible government is a Fine Gael–Labour coalition. Alternatively, if Fine Gael comes within striking distance of an overall majority, giving a 'cliffhanger' dimension to proceedings, then the result may not emerge until late on Sunday 27th.

Background

To sum up nearly four years of political developments in one paragraph: The 3-party coalition between Fianna Fáil, the Green Party and the Progressive Democrats (PDs) took office in June 2007, with the support of nearly 90 of the 166 TDs and a five-year term ahead of it. By the time Brian Cowen succeeded Bertie Ahern as Taoiseach in May 2008 not much had changed. However, over the next two years the economy took a massive downward turn (the legacy more of decisions made between 2001 and 2008 than of the decisions made once the extent of Ireland's property bubble and reckless lending and borrowing by the banks became clear); the PDs dissolved; and the number of FF TDs decreased through death, resignation from the Dáil, or defection from the party. When the Greens withdrew from the government in January 2011 the end was near. The last days of the 30th Dáil were thrown into further confusion by challenges to Brian Cowen's leadership of FF, a consequence of the party's plummeting poll ratings rather than of any fundamental disagreements on policy matters. He won a majority of votes in a confidence vote among his TDs on 18 January but, after the Greens' withdrawal from government, stood down as FF leader on the 22nd, and on 26 January Micheál Martin was elected as FF leader. Thus FF fought the campaign with a government headed by Brian Cowen, who did not stand for re-election to the Dáil, and a rather different front bench appointed by the new leader.

What are the issues?

Not surprisingly, the country's economic difficulties constitute far and away the most important issue according to respondents to opinion polls, and the second biggest issue cited, unemployment, could be seen as essentially a consequence of the main issue. To a certain extent this is a 'valence' issue, with the main parties agreeing that economic recovery should take priority over all other goals and yet unable to disagree much on specific policies, if only because the hands of all governments are tied by the constraints and commitments that are part of the loan provision / bailout agreed by the outgoing government with the EU, the European Central Bank and the IMF in December 2010.

Position-based debate mainly concerns the terms of this loan provision / bailout. Some commentators say that Ireland simply will not be able to repay its debts, especially those incurred by reckless borrowing across the Eurozone by Irish banks, and that a lower interest on the funds provided under the agreement, a degree of debt forgiveness, and / or a 'burning' of the bondholders is necessary if it is to avoid bankruptcy (for informed discussion of such matters, see the Irish economy site). There is general agreement that, morally, bond-holders and banks that lent to the Irish banks money that those Irish banks in turn lent recklessly to property speculators should have to accept the consequences of their unwise investments, and that the Irish people should not have to 'repay' loans that they did not take on and knew nothing about, but there is uncertainty as to what can be done. The main opposition parties, Fine Gael and Labour, argue that the terms of the loan are unacceptable and that in government they will renegotiate these terms, insisting on a better deal for Ireland. Fianna Fáil maintains that, while there may be scope for some EU-wide easing of the terms on which the ECB lends, and that this is already under way, it is delusional or deceitful for the opposition to pretend that there is any possibility of the package being fundamentally renegotiated, and it says that the terms of the 'bailout' enable Ireland to borrow the money that it needs to fund its annual budget deficit at significantly lower rates than it would have to pay in the open market. Parties further to the left than Labour (Sinn Féin and the United Left Alliance) advocate rejecting the IMF / ECB / EU loan entirely and the repudiation of some or all of the debt. Funds to bridge the gap between government and expenditure could come either from taxing the wealthy, they say, or from the bond markets which, noting that Ireland is now debt-free (having repudiated its current debt), will be willing to lend it money at reasonable interest rates. The other parties regard these scenarios as well into the realms of fantasy, asking who would lend more money to a country with a record of debt repudiation, but, given the widespread feeling in Ireland that the ECB and EU have been motivated much more by a desire to protect the euro and the interests of banks in some major Eurozone countries than to assist Ireland, the expectation is that the parties and groups advocating this rejectionist approach will receive a significant protest vote.

Political reform is also being discussed by all of the parties, and a group of researchers have 'scored' all the parties' proposals in this area, constructing an index based on a number of criteria concerning local government, public sector, open government, electoral, and Oireachtas; details here.

Visiting journalists sometimes express disappointment at the tone of the election. Given Ireland's current economic difficulties, plus the huge drop in support for the political party that has been dominant ever since 1932, many see this as the most important election for many years, a momentous occasion for the Irish people, a moment of decision that will decide the fate of the country for many years into the future. However, upon arriving in Ireland they sometimes find that it is not clear what the policy choices facing the electorate are, and that it seems likely that in policy terms not much will change greatly whatever the election outcome; that many voters already seem bored with the campaign; and that commentators have pronounced this one of the most lacklustre campaigns ever (admittedly, this is said about pretty much every campaign).

Which parties will form the next government?

In a multi-party system there are a number of possible combinations of parties. A coalition between the two main opposition parties, Fine Gael and Labour, has long seemed to most observers to be almost inevitable, though relations between the two parties are not warm and each occasionally accuses the other of being open to the idea of making some kind of post-election deal with Fianna Fáil – if not a formal coalition, then perhaps an arrangement whereby FF would support a minority government of FG or Labour. This is unlikely but, barring an unexpected surge in support for either Fine Gael or Labour, has seemed to be the only remotely feasible alternative to the expected FG-Labour coalition government, given that both Fine Gael and Labour have firmly ruled out any coalition with either Fianna Fáil or Sinn Féin. Signs of a rise in support for FG have led to speculation that a continuation of this trend might yet enable the party to form a minority single-party government, perhaps with the support of 'like-minded independents', should enough of these be elected.

The 'identifiability' of government options - that is to say, whether voters are confronted with clear choices or whether, as is sometimes the case in multi-party systems, the options are unknown and emerge only out of post-election negotiations - varies from country to country and from election to election. At Ireland's 2007 election, identifiability was very low. On election day, the betting markets listed 11 possible governments, with the most likely (FF + Labour) having a probability of only 30 per cent; the eventual government, FF + Greens + PDs, was perceived as being only the fifth most likely outcome, with a probability of just 8 per cent (more on this at page on betting and politics).

In 2011, in contrast, the betting market suggests that identifiability is very high and indeed that there scarcely are any real 'options'. The perceived likelihood of a FG-Labour government started at around 80+ per cent, with other possibilities (a FG minority government, a coalition between FG and FF) lagging well behind. It has dropped since then as FG has grown in support according to the polls, but is still given a probability of around 60–65 per cent. The main 'choice' facing voters, it seems, is what the relative strengths of Fine Gael and Labour will be, which will determine how many government seats each party can claim and on whose terms policy differences between the two parties are settled. This partly accounts for what seems the tendency of both FG and Labour to direct their fire towards each other rather than towards the government; the fewer seats the other party wins at the election, the fewer positions it will be entitled to in the presumed post-election FG–Labour coalition. The risk is that it may make the construction of a post-election programme for government more difficult, and may adversely affect the degree of trust between the parties in the next government, a factor that tends to be important for government efficacy and survival.

The fact that the composition of the next government is seemingly so certain, and hence hardly a matter that voters need agonise over when they cast their ballots, could give the election a slightly 'second-order' aspect in some voters' minds. At second order elections, such as EP or local elections, voters characteristically move away not just from the government but also from other large, 'established', parties. If this occurs, there may be a marked increase in support for Independents in particular, and if the demand for independent candidates increases then the supply is certainly there to meet it, with around 200 standing.

Candidates

The number of candidates for the 165 contested seats is 566, by some way a record. The number ranges from 24 in Wicklow, 21 in Laois–Offaly, 19 in Carlow–Kilkenny, down to 8 in Kildare S, Tipperary N and Tipperary S. As usual, women are heavily under-represented among candidates, with over five times as many male candidates as females:

Total |

Men (N) |

Women (N) |

Men (%) |

Women (%) |

|

| Fianna Fáil | 75 |

64 |

11 |

85.3 |

14.7 |

| Fine Gael | 104 |

88 |

16 |

84.6 |

15.4 |

| Labour | 68 |

50 |

18 |

73.5 |

26.5 |

| Sinn Féin | 41 |

33 |

8 |

80.5 |

19.5 |

| Green Party | 43 |

35 |

8 |

81.4 |

18.6 |

| United Left Alliance | 20 |

15 |

5 |

75.0 |

25.0 |

| Christian Solidarity Party | 8 |

7 |

1 |

87.5 |

12.5 |

| Workers Party | 6 |

6 |

0 |

100.0 |

0 |

| New Vision | 20 |

18 |

2 |

90.0 |

10.0 |

| Fís Nua | 5 |

5 |

0 |

100.0 |

0 |

| Others and Independents | 176 |

160 |

16 |

90.9 |

10.1 |

| Total | 566 |

480 |

86 |

84.8 |

15.2 |

The United Left Alliance consists of the Socialist Party (8 candidates), People before Profit (9 candidates), and the Workers and Unemployed Action Group (1 candidate), as well as two other left-wing candidates. New Vision is 'an association of independent candidates, working together to change the way we 'do' politics in Ireland'. The name 'Fís Nua' translates into English as 'New Vision', but Fís Nua, which aims to remove corruption from public and political life, emphasises that it has no connection with the 'New Vision' group.

The number of female candidates is up very marginally on 2007, when it was 82, but given the large increase in the number of male candidates the proportion of women is even lower than in 2007, when it was 17.4 per cent. In 2007, the average male candidate received 4,506 first preferences, and the average female candidate 3,872 first preferences. It would be wrong, though, to infer that women candidates receive fewer first preferences than men, because female candidates tended to start with fewer political resources (major party label, elective status) than male candidates, and once these factors are controlled for the picture becomes more nuanced. On average, each of the 470 candidates received 4,395 first preferences.

Nearly half the candidates have no elective status (or, at most, are members of town councils):

Number |

% |

|

| Government minister | 6 |

1.1 |

| Junior minister | 12 |

2.1 |

| Other TD | 108 |

19.1 |

| Senator | 25 |

4.4 |

| MEP | 2 |

0.4 |

| Member of county or city council | 154 |

27.2 |

| None of the above | 259 |

45.8 |

| Total | 566 |

100.0 |

In 2007, the average number of first preference votes won by candidates was strongly related to their elective status, from 11,299 for cabinet ministers to 7,197 for non-ministerial TDs down to 1,563 for those with no elective status. Fuller details can be found in How Ireland Voted 2007.

Of the 566 candidates, 229 also stood in 2007: 55 of the FF candidates, 61 from FG, 32 from Labour, 22 from Sinn Féin, 17 from the Green Party, 8 from the ULA, 3 of the CSP candidates, 2 WP candidates, 1 from FN, 1 from NV, and 27 others. Not all are standing under the same label as in 2007.

How many women TDs will there be in the 31st Dáil?

The highest number of female TDs elected at a general election is 22 out of 166 (13%) in both 2002 and 2007. This placed Ireland in joint 104th position at the start of February 2011, according to the IPU's database, once the adjustments necessitated by that database's eccentric ranking system are made. It has been argued that candidate selection patterns do not lead to any great confidence that this low percentage will be exceeded in 2011. However, this may be too pessimistic.

Predicting the overall distribution of seats is difficult enough, and predicting the identity of the 165 TDs to be elected is even harder. Based mainly on the overall standings of the parties, and the assessments of those with detailed knowledge of the constituencies, we can divide candidates into those who at this stage seem virtually certain to be elected or who at least have a strong likelihood of election; those whose chances seem to be somewhere around 50-50; and those whose chances do not seem high (but who may, of course, yet defy the predictions). Undoubtedly, some of these assessments will change over the course of the rest of the campaign, and the lists below have been updated regularly.

On this basis, we might predict a record number of female TDs in the 31st Dáil. There are 19 who seem to have a very strong chance of election or re-election, and a further 23 who seem to have a reasonable chance. If we were to assume that around 90 per cent of the first category, and around a third in the second category, are successful, this would give a total somewhere around 25 (15.1 per cent). Given that this figure, while still low by comparative standards, is significantly higher than the previous record number of 22, it seems that even allowing for the near-certainty of several errors in these assessments, there is a strong chance that there will be more female TDs than ever before. [Post-election comment: in the event there were precisely 25 female TDs elected: 17 of the 19 in the first category, and 8 of the 23 in the second category.]

Virtually certain / strong chance (19):

FF (0):

FG (9): Heather Humphreys (Cavan–Monaghan), Deirdre Clune (Cork SC), Frances FitzGerald (Dublin MW), Olivia Mitchell (Dublin S), Catherine Byrne (Dublin SC), Lucinda Creighton (Dublin SE), Fidelma Healy-Eames (Galway W), Nicky McFadden (Longford–Westmeath), Michelle Mulherin (Mayo)

Labour (6): Ann Phelan (Carlow-Kilkenny), Kathleen Lynch (Cork NC), Joanna Tuffy (Dublin MW), Róisín Shortall (Dublin NW), Joan Burton (Dublin W), Jan O'Sullivan (Limerick City)

SF (1): Mary Lou McDonald (Dublin Cen)

Others (3): Maureen O'Sullivan (Ind, Dub Cen), Clare Daly (ULA-SP, Dublin N), Catherine Murphy (Ind, Kildare N)

Chances somewhere in a broad range around 50-50 (23):

FF (7): Margaret Conlon (Cavan–Monaghan), Mary Coughlan (Donegal SW), Maria Corrigan (Dublin S), Mary Hanafin (Dun Laoghaire), Aine Brady (Kildare N), Mary O'Rourke (Longford–Westmeath), Máire Hoctor (Tipperary N)

FG (6): Aine Collins (Cork NW), Cait Keane (Dublin SW), Mary Mitchell O'Connor (Dun Laoghaire), Marcella Corcoran Kennedy (Laois–Offaly), Regina Doherty (Meath E), Catherine Yore (Meath W)

Labour (6): Ivana Bacik (Dun Laoghaire), Marie Moloney (Kerry S), Jenny McHugh (Meath W), Phil Prendergast (Tipperary S), Ciara Conway (Waterford), Anne Ferris (Wicklow)

SF (2): Kathryn Reilly (Cavan-Monaghan), Sandra McLellan (Cork E)

Others (2): Joan Collins (ULA-PbP, Dublin SC), Catherine Connolly (Ind, Galway W)

Opinion polls

Because of the small district magnitudes employed in Ireland (an average of only 3.8 TDs per constituency, exceptionally low by the standards of PR systems worldwide) a certain degree of disproportionality, and unpredictability in the national seats:votes ratio, is inevitable. In addition, the transferability of votes provided for by the PR-STV electoral system (click here for discussion of arguments for and against this system) means that there is no automatic translation of a certain percentage of first preference votes into a certain number of seats. Attempts to convert vote figures, as measured by opinion polls, into seats may be done either by assessing the effect of a given shift in voting strength on each individual constituency and adding up the results (this is done for most polls by Dr Adrian Kavanagh of NUI Maynoooth; see his contributions to the Political Reform site) or by doing the calculations at national level and taking into account factors specific to each party (for the rationale, the caveats and the uncertainties, see another contribution to the Political Reform site). Most predictions are that FG will win more seats, and SF fewer, than in the projections below.

Summarising, the latter method assumes that FF will receive more or less its proportionate share of seats, benefiting from being (still) one of the largest four parties but suffering from the likelihood that other parties' supporters will use their lower preferences against it; FG will benefit from its size but will not attract many transfers except from Labour voters; Labour will attract transfers from across the board, but it remains to be seen how the party copes with the tensions and difficulties that can arise when a party expands its number of candidates; Sinn Féin will be more transfer-attractive than ever before but many of its candidates are relatively unknown. Employing this latter method, this is the way the polls so far point:

Publisher |

Polling organisation |

Fieldwork ended | Date published |

% votes |

|||||

FF |

FG |

Lab |

SF |

Others |

|||||

| Election 2007 | 42 |

27 |

10 |

7 |

14 |

||||

| 1 | Sunday Independent | Millward Brown | 27 Jan | 30 Jan | 16 |

34 |

24 |

10 |

16 |

| 2 | Sunday Business Post | Red C | 27 Jan | 30 Jan | 16 |

33 |

21 |

13 |

17 |

| 3 | Irish Independent | Millward Brown | 30 Jan | 2 Feb | 16 |

30 |

24 |

13 |

15 |

| 4 | Paddy Power | Red C | 1 Feb | 2 Feb | 18 |

37 |

19 |

12 |

14 |

| 5 | Irish Times | Ipsos / MRBI | 1 Feb | 3 Feb | 15 |

33 |

24 |

12 |

16 |

| 6 | Sunday Business Post | Red C | 2 Feb | 6 Feb | 17 |

35 |

22 |

13 |

13 |

| 7 | Sunday Business Post | Red C | 10 Feb | 13 Feb | 15 |

38 |

20 |

10 |

17 |

| 8 | Irish Independent | Millward Brown | 13 Feb | 16 Feb | 12 |

38 |

23 |

10 |

19 |

| 9 | Sunday Business Post | Red C | 16 Feb | 20 Feb | 16 |

39 |

17 |

12 |

16 |

| 10 | Sunday Independent | Millward Brown | 16 Feb | 20 Feb | 16 |

37 |

20 |

12 |

15 |

| 11 | Irish Times | Ipsos / MRBI | 17 Feb | 21 Feb | 16 |

37 |

19 |

11 |

17 |

| 12 | Irish Independent | Millward Brown | 21 Feb | 23 Feb | 14 |

38 |

20 |

11 |

17 |

| 13 | Paddy Power | Red C | 22 Feb | 23 Feb | 15 |

40 |

18 |

10 |

17 |

| 14 | RTE exit poll | Millward Brown | 25 Feb | 26 Feb | 15.1 |

36.1 |

20.5 |

10.1 |

18.2 |

| Election result | 25 Feb | 17.4 |

36.1 |

19.4 |

9.9 |

17.2 |

|||

Poll |

Date published |

Projected seats |

||||

FF |

FG |

Lab |

SF |

Others |

||

| Election 2007 | 78 |

51 |

20 |

4 |

13 |

|

1 |

30 Jan | 27 |

60 |

44 |

17 |

18 |

2 |

30 Jan | 27 |

58 |

38 |

22 |

21 |

3 |

2 Feb | 27 |

54 |

45 |

22 |

18 |

4 |

2 Feb | 31 |

65 |

35 |

21 |

15 |

5 |

3 Feb | 26 |

58 |

44 |

21 |

17 |

6 |

6 Feb | 29 |

62 |

40 |

22 |

13 |

7 |

13 Feb | 26 |

67 |

37 |

17 |

19 |

8 |

16 Feb | 21 |

67 |

42 |

17 |

19 |

9 |

20 Feb | 27 |

68 |

31 |

21 |

19 |

10 |

20 Feb | 27 |

65 |

37 |

21 |

16 |

11 |

21 Feb | 27 |

65 |

35 |

19 |

20 |

12 |

23 Feb | 24 |

67 |

37 |

19 |

19 |

13 |

23 Feb | 26 |

70 |

34 |

17 |

19 |

14 |

26 Feb | 26 |

64 |

38 |

18 |

20 |

| Election result | 20 |

76 |

37 |

14 |

19 |

|

[Post-election comment:

The RTE exit poll was very accurate. It estimated FG support precisely and was very close for SF, but slightly over-estimated Labour and Others while being more than 2 percentage points too low for FF. The last of these may suggest that there really were, as many had speculated, 'secret' FF supporters who voted for the party while being reluctant to admit this to pollsters.

It can be seen that projecting vote shares into seats using the method adopted here produces figures that turn out to be much too low for FG, rather too high for FF and SF, and about right for Labour and for Others. FG did so well (46 per cent of the contested seats for 36 per cent of the votes) mainly because of the potential for disproportionality introduced by Ireland's exceptionally small constituency size; its average of only 3.8 MPs per constituency is well below the number generally reckoned to be necessary to deliver a high degree of overall proportionality. As the largest party, and especially given that it was around twice as strong as the next strongest, FG was in a position to benefit significantly if it 'managed' its votes optimally, and in most constituencies it did this. Consequently, it received a larger seat bonus than any party has achieved at any previous election. ]

Could Fine Gael win an overall majority of seats?

Increasingly, discussion is turning to the question of whether FG can win an overall majority, or at least enough seats to be able to form a minority single-party government with Independent support. This seems unlikely, though it is not impossible. It could happen if the deviations from proportionality were larger than those anticipated by the method used to generate the table above. The biggest over-representation achieved by any party in the history of the state was achieved by FF in 2002, when it won 49 per cent of the seats with 41 per cent of the votes, a full 12–13 seats more than its proportionate share. It benefited from not being the party that most other parties’ supporters ranked last, as had usually been the case prior to 1997, and also from its size. When district magnitude (the number of TDs elected per constituency) is small, disproportionality is inevitably generated, and the largest party is usually the main beneficiary. In this country, district magnitude is only 3.8 on average, exceptionally low for any country using any form of proportional representation. In addition, in 2002 FF benefited from the unusually large vote for Independents and ‘others’; even though Independents were elected in near-record numbers, with 13 of them returned to the Dáil, groups outside the three main parties still received about 9 fewer seats than if their seat total had matched their share of the votes.

Some of this, especially the last point, is likely to apply this time as well. With a massive 319 candidates outside the three main parties (or 278 if SF is included in the ‘main parties’), it is quite possible that this vote will be ‘shredded’, dispersed among a number of candidates, and unlikely to transfer solidly to any candidate or party in particular. This would mean that the larger parties will pick up the seats that Independents do not secure, and that they have the scope to achieve an unusually high votes --> seats conversion rate. FG is unlikely to benefit significantly from transfers from most other parties or candidates – both Labour and SF may fare better here – and, indeed, if it looks possible that FG can form a government without Labour, Labour voters have every incentive to use their transfers against FG to prevent this happening. Why would Labour voters give a lower preference to a FG candidate if the effect could be to make Labour irrelevant in the government formation process? On the other hand, FG may do much better than usual in transfers upon the elimination of FF candidates. Besides, in order to be disproportionately over-represented, the largest party does not need to be particularly transfer-attractive to other parties, it merely needs to avoid being transfer-repellent. If FG were to replicate FF's 2002 achievement of winning around 13 seats more than its proportionate share, then it would require 42–43% of the votes in order to win 83 seats.

Looking at this at the level of individual constituencies: in order to win an overall majority FG would need to win a majority of seats in a number of constituencies and avoid ending up with a minority in more than a few. In 2007 the party won a majority in only 3 constituencies (Cork SW, Mayo, Roscommon–Leitrim S) and won a minority in 35.

In 2011 FG seems to have very little chance of winning a majority in most constituencies, and there are several where it is on course for only a minority, even, in several cases, if all of its candidates there were elected.

Constituencies where it is certain or almost certain to win a minority of seats:

3-seaters: Donegal NE, Donegal SW, Dublin NE, *Dublin NW, Kerry N–Limerick W, Kildare S, Tipperary N, Tipperary S

4-seaters: Cork NC, Dublin Central, Dublin N, Dublin SW, Kildare N

5-seaters: Cavan–Monaghan, *Dublin SC, Galway W

* super-minority possible, ie 0 seats in a 3-seater or 1 seat in a 5-seater

[Post-election comment: FG won a majority of seats in just one of these constituencies, Cavan–Monaghan, and did win a super-minority in Dublin NW and Dublin SC]

Constituencies where FG is almost certain to win half or fewer of the seats:

4-seaters: Clare, Cork E, Dublin MW, Dublin SE, Dublin W, Dun Laoghaire, Galway E, Limerick City, Longford–Westmeath, Louth, Waterford

[Post-election comment: this was the case in each of the constituencies listed]

Constituencies where it has at least a possibility of winning a majority of seats:

3-seaters: Cork NW, Cork SW, Dublin NC, Kerry S, Limerick County, Meath E, Meath W, Roscommon–Leitrim S, Sligo–Leitrim N

4-seaters: none

5-seaters: Carlow–Kilkenny, Cork SC, Dublin S, Laois–Offaly, *Mayo, Wexford, Wicklow

* super-majority possible, ie 4 seats in a 5-seater

[Post-election comment: despite winning the super-majority in Mayo, FG did not achieve a majority in Dublin NC, Kerry S, Cork SC or Laois–Offaly.]

All of this suggests that an overall FG majority is highly unlikely, albeit not impossible. [Post-election comment: given that FG won 76 seats with 36 per cent of the first preference votes, it remains possible that it could have achieved an overall majority with 40 per cent of the votes.]

How reliable are opinion polls?

Hard to be certain, in that any disparity between the findings of a poll conducted several weeks before polling day, and the result on election day, may well be due to a shift in opinion rather than to inaccuracy in the poll. When polls concur, that increases our confidence in their accuracy, and on the whole the polls these days do usually tell very similar stories. For more discussion see posts on Political Reform site.

In 2002, the polls, basically, 'got it wrong', pointing to a FF overall majority, but the polling companies made some adjustments to their methodology after that and in 2007 they did much better. Their performance at those two elections is analysed in chapters by Gail McElroy and Michael Marsh, both of TCD's Department of Political Science, in the books How Ireland Voted 2002 and How Ireland Voted 2007 (full details of these in 'Further information' below).

The How Ireland Voted 2007 chapter on the polls, incidentally, says that the first poll of the campaign recorded levels of support for FF at 37 per cent, and its lowest figure at any stage during the campaign was 35 per cent. Despite this, some in FF are claiming during the current campaign that in 2007 it started at 30 per cent and finished at 41 per cent, the implication being that if its campaign in 2007 could produce an 11-point increase in its support, perhaps the 2011 campaign could have the same effect. Maybe those quoting the figure of 30 per cent are referring to the so-called 'core support' (the now conventional term for the percentages when the don't knows are included), but to use that as the base would not be comparing like with like.

Predictions

In 2007 these were not great, most of them significantly underestimating FF and overestimating SF and the Greens. A list could be found at ElectionsIreland.

There was an 'election prediction game' at fullhouse.whitebox.ie, with predictions about the national level outcome, constituency outcomes, and the fates of individual candidates.

Perhaps the most useful source of predictions is the betting market, which if working efficiently distils observers' assessments into quantifiable probabilities, though there are caveats. In 2011 some thought that the overwhelming perception that the composition of the next government and the identity of the next Taoiseach are pretty much foregone conclusions (FG + Labour; Enda Kenny) would mean that the betting markets are smaller than in 2007, but in fact the volume of betting is reportedly up on 2007. Click here for discussion. Betfair had a site on the election, which supplies a running prediction of the number of seats that each party will win.

In 2007 the betting market was good on the question of who would be next Taoiseach but performed poorly on the composition of the next government. When it comes to identifying constituency winners, the size of each constituency market is fairly small, which means that its 'predictions' must be treated with especial caution. In 2007, 20 candidates priced at 1–3 or shorter were defeated, including Dan Boyle at 1–33 and Seán Crowe at 1–20, so not all of the bookmakers' apparent certainties are in fact certain to be elected. Several long-priced losers in 2007 are at similar prices in 2011. The betting market on individual constituencies should be regarded as a pointer to candidates' prospects, but no more. However, it is true that the overwhelming majority of winners came from the short-priced candidates. In only 13 constituencies did a candidate priced at longer than evens win, and the longest priced winner was Ciarán Lynch at 5–2. Fuller details in Chapter 9 of How Ireland Voted 2007.

Party gains and losses are never uniform across the country - hence the cliché that there is not one election but 43 mini-elections, one in each constituency - so it is impossible to identify one key barometer constituency and say 'how that goes, so goes the country'. In 2007, as it turned out, Dublin NE pretty much summed up the major themes of the result: FF did better than expected but did not quite achieve an overall majority; FG recaptured some of the ground lost in 2002; both Labour and the Greens more or less held their own; SF failed to make the gains expected. However, there was no way of identifying this as a bellwether constituency before the election.

Records

Most predictions suggest that this will not be an election of incremental adjustments in the strengths of the parties but will witness dramatic changes. A number of existing 'records', whether highs or low, may be broken, and the phrase '... the --est since the foundation of the state' may fill the airwaves as the results come in, and even before. Though cynics will say 'plus ça change ...'

There is a record number of candidates: 566 of them excluding the Ceann Comhairle, compared with the previous record of 484 in 1997. With FF reducing its number to 75 (previous record low 87, way back in June 1927), the reason for the upsurge was a huge increase in the number of independents, from 85 in 2007 to around 200 (depending on precisely how an independent is defined) in 2011. FG is running 104, which is its highest since November 1982 but well short of its highest ever (126 in 1981). This is only the second time since 1927, the other being 1969, that FG has run more candidates than any other party. Labour's 68 candidates represents its third highest number ever, previous peaks being 70 in 1943 and the extraordinary 99 in its Icarus-like 1969 election campaign. Fianna Fáil's candidate pattern is especially remarkable, in that the party is running fewer candidates (75) than it won seats in 2007 (78). This is the first election since 1927 at which Fianna Fáil is not attempting to enter government after the election, and the first election ever at which it is running insufficient candidates to win an overall majority even if they were all elected.

FF's lowest ever vote is 26.1% (June 1927), and its lowest vote since 1932 is 39.1% (1992). Its lowest number of seats is 44 (June 1927) and its lowest since 1932 is 65 (1954). If it does not fall below all of these figures in 2011 it will regard its campaign as a success. [Post-election comment: FF did receive a new record low number of votes and of seats.]

FF has won a plurality of seats at every election going back to 1932. In June 1927 it won a seat in every constituency except for Cork North (and even there a FF-leaning independent won a seat), and at every election since then it has won at least 1 seat in every constituency. Neither record is likely to stand after the 2011 election. [Post-election comment: These records indeed did not stand; in fact, 25 of the 43 constituencies, and 8 of the 26 counties, are now unrepresented by a FF TD.]

FG's maximum vote share is 39.2% (Nov 1982) while its seat maximum is 70 (also Nov 1982). It is possible, though not probable, that it will achieve new record highs. It has not been the largest party since Sept 1927 when its forerunner, Cumann na nGaedheal, outpolled all other parties, but it is expected to achieve that distinction in 2011. [Post-election comment: FG won more seats than ever before, but in votes it fell 3 percentage points short of its November 1982 figure.]

FF and FG together have never won fewer than 53.6% of the votes (June 1927); that election apart, their lowest combined totals are 61.7% (1948) and 63.6% (1992). According to most polls, their combined vote in 2011 will be below 60%, and possibly even below the June 1927 figure; some polls even find them to have the support of fewer than 50% of respondents. Their lowest combined seat total is 90 (June 1927 again); since 1948 they have never fallen below 108 seats (1951). It would take a remarkable campaign effect in 2011 to bring their combined seat total into three figures. [Post-election comment: FF + FG between them won 1,118,986 votes, or 53.549 per cent, compared with 53.573 percent in June 1927, so, by the narrowest of margins (0.024 per cent), they won between them fewer votes than ever before. Their combined seat total, 96, was higher than in June 1927.]

Labour's vote maximum is 21.3% (way back in 1922, when vote shares were distorted by the Collins-de Valera pact and by a high number of uncontested seats); in modern times its maximum is 19.3% (1992). Its seat maximum is 33 (also in 1992). As of the start of the campaign, it would represent a major surprise, and a big disappointment for the party, if it does not push both to new record highs in 2011. In addition, it expects to be one of the strongest two parties; hitherto it has always been either the third or the fourth strongest party. [Post-election comment: Labour's vote marginally exceeded its 1992 figure, though not its 1922 level, and it won a new record number of seats.]

The biggest inter-election loss for any party is the 23 seats lost by FG between the elections of 1997 and 2002. FF's biggest seat loss was 9 seats, between 1989 and 1992. FF won 77 seats in 2007, so unless it wins at least 56 seats this time, a remote possibility according to all predictions, it will set a new unwanted record here. [Post-election comment: FF shattered all records here.]

The biggest inter-election gains are those of FG, which gained 22 seats between 1977 and 1981 (aided by the size of the Dáil increasing significantly) and 20 between 2002 and 2007. Labour's largest advance was 18 seats between 1989 and 1992. In 2011 FG needs to win 73 seats and Labour 38 to equal their previous largest seat gains. [Post-election comment: FG established a new record here, with a gain of 25 seats.]

The largest number of seats commanded by a government is 101 out of 166 (the FF-Labour government elected in 1993, which lasted less than two years). FG and Labour together are on course for around this number of seats between them. [Post-election comment: FG and Labour won 113 seats between them, a new record for a government.]

Turnover: the largest number of TDs deciding not to contest an election was 29 in June 1927; subsequent highs have been 26 in 1969 and 22 in 2002. This record has already been broken, with 36 TDs deciding not to contest, including 10 former cabinet ministers. These were 21 from FF (including two current / former Taoisigh), 8 from FG, 4 from Labour, 1 from SF and 2 independents. A further 3 seats were vacant at the time of the dissolution due to earlier retirements. The highest number of TDs to be defeated was 41, also in June 1927; since 1981, the average number of TDs to lose their seats at each election is 26. With so many of those FF TDs who faced defeat in 2011 having decided to retire, and the overwhelming majority of FG, Labour and SF TDs likely to be re-elected, this record may remain intact.

The other side of this coin is the number of new TDs (that is, people who were not in the 30th Dáil; some of those elected are likely to be former TDs returning to the Dáil, such as Frances Fitzgerald (FG), Eric Byrne (Lab), Seán Crowe (SF), Joe Higgins (SP) and Catherine Murphy (Ind)). Here the records were set in the very early years of the state: 77 new faces in 1923 and 71 in June 1927. Since then, the largest number has been 56 in 1981, due mainly to the large increase (from 148 to 166) in the size of the Dáil. At the eight elections since then, during which period the size of the Dáil has remained stable, the average number of candidates elected who were not members of the previous Dáil has been 41. Noel Whelan has estimated that there may be 60 or 70 new faces in the 31st Dáil. [Post-election comment: In the event, a majority of those elected, 84 out of 166, were not in the previous Dáil – another record.]

Fractionalisation (roughly, how concentrated or dispersed the votes or seats are): the most fragmented Dáil by a long way was that elected in June 1927 (effective number of parties 4.85; a figure of, say, 4, means that the Dáil is as fragmented as if there are 4 equal-sized parties there). Since then, the highest figure has been 3.66 (1948). The 2011 election may well produce the most fractionalised Dáil since 1927. The Dáil elected in June 1927, incidentally, lasted less than three months, and there was another general election in September 1927. [Post-election comment: In terms of votes, fractionalisation was at its highest since June 1927; in terms of seats, the Dáil was a little less fractionalised than that of 1948, mainly because FG won more seats and FF fewer seats than some had expected.]

Disproportionality (disparity between vote shares and seat shares) is unlikely to reach record highs. The three elections to produce the highest levels are those of 1997, 2002 and 2007 - the 2002 figure of 6.62, measured by the least squares index, being the highest. It is highest when the largest party, which receives a seat bonus anyway simply by benefiting from its size, achieves a further bonus due to transfers from an ally, as FF did from the PDs in 1997, 2002 and 2007. Transfer rates between parties in 2011 are unlikely to be particularly high. [Post-election comment: In the event, FG's dominance in the vote, with more than twice as many votes as any other party, allowed it to gain a record bonus given the very small district magnitudes used in Ireland (average dm only 3.8 seats per constituency), and FF was highly under-represented, so 2011 did establish a new record for disproportionality.]

Further information

Due to time constraints it is unfortunately not always possible to respond to every question about the election campaign: what the main issues are, how the Dáil is elected, what the opinion polls have been saying, what the choices facing the voters are, which campaigning techniques are most effective, what the various parties stand for, who's likely to win, etc. Those seeking information might find the following sources useful, though of course there is the usual caveat that this page is not responsible for the content of external sites:

How Ireland Voted 2007 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). Account of the last Irish general election: what happened, what the main issues were, how accurate or otherwise the polls were, how much impact the campaign had, the impact of party leaders upon their parties' electoral fortunes, where and how the election was won and lost, how much swings varied across the country, which parties were best placed for next time, and so on; plus 37 pages of photographs. What lessons can parties and analysts learn about the 2011 campaign from the record of the 2007 campaign? How much impact does a TV leaders' debate make?

Politics in the Republic of Ireland, 5th ed (Abingdon: Routledge and PSAI Press, 2010), ISBN 978-0-415-47671-3 (hardback), 978-0-415-47672-0 (paperback). This has chapters on every aspect of politics and government, including a chapter explaining and assessing the distinctive PR-STV electoral system plus one on electoral behaviour.

Data from the INES (Irish National Election Study, principal investigator Michael Marsh of TCD) is accessible on-line.

How Ireland Voted 2002 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003). Account of the 2002 Irish general election, with same format as 2007 volume; plus 17 pages of photographs.

For those who seek an informed view concerning the impact of developments in Northern Ireland upon politics south of the border, and the implications of the 2011 election for the Northern Ireland peace process, then a hub of expertise is the Institute of British-Irish Studies at UCD.

The Politics of Electoral Systems, paperback edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), ISBN 978-0-19-923867-5. Has a chapter explaining and examining PR-STV in Ireland in the context of electoral systems worldwide, asking how far aspects of Ireland's politics can be attributed to PR-STV. This chapter contains the reproduction of a PR-STV ballot paper, which you can view here.

Days of Blue Loyalty (Dublin: PSAI Press, 2002), ISBN 0-9519748-6-6. Analysis of a survey of members of the Fine Gael party published shortly before the 2002 election. Fine Gael fared very badly at that election, but the survey pointed to a commitment among its membership, which has been one factor determining its rise since then. This book explores the worldview, backgrounds and activity levels of the party's members.

Listings of candidates in individual constituencies, and information on many of them, can be found at the ElectionsIreland site.

The national broadcaster RTE had an Election 2011 site, and there were several other 2011 elections sites in operation such as election2011.ie.

Predictions are to be found on both the Betfair site and the fullhouse site (see under 'Predictions' section above).

How Ireland Voted 2011. Not published yet, for obvious reasons - publication by Palgrave Macmillan expected in September 2011, in good time for the christmas market.

If you want to talk direct to an academic who studies Irish elections then, in the event of no-one from Trinity College being available, examination of the Political Reform site may lead you to a suitable authority, and in particular Dr Adrian Kavanagh maintained a 2011 election site.

For commentary and discussion on matters of economic policy - should and will the bondholders be burned, can Ireland afford to repay the loans it has drawn down or may draw down from the ECB and IMF, what is the likelihood that the terms can be renegotiated by the next government, etc - see the Irish economy site.

And should you wish to study for a postgraduate degree in Politics, the Department of Political Science at Trinity College Dublin has highly regarded postgrad programmes.

Results 2007

The results of the Dáil election 2007 are fully analysed in the best-selling How Ireland Voted 2007 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). They were:

| 2007 election result | Candidates |

Votes |

% vote |

Change since 2002 |

Seats |

Change since 2002 |

% seats |

|

| Fianna Fáil | 106 |

858,565 |

41.56 |

+0.08 |

77 |

-4 |

46.67 |

|

| Fine Gael | 91 |

564,428 |

27.32 |

+4.84 |

51 |

+20 |

30.91 |

|

| Labour | 50 |

209,175 |

10.13 |

-0.65 |

20 |

0 |

12.12 |

|

| Green Party | 44 |

96,936 |

4.69 |

+0.85 |

6 |

0 |

3.64 |

|

| Sinn Féin | 41 |

143,410 |

6.94 |

+0.43 |

4 |

-1 |

2.42 |

|

| Progressive Democrats | 30 |

56,396 |

2.73 |

-1.23 |

2 |

-6 |

1.21 |

|

| Socialist Party | 4 |

13,218 |

0.64 |

-0.16 |

0 |

-1 |

||

| People before profit / SWP | 5 |

9,333 |

0.45 |

+0.27 |

0 |

0 |

||

| Workers Party | 6 |

3,026 |

0.15 |

-0.07 |

0 |

0 |

||

| Christian Solidarity Party | 8 |

1,705 |

0.08 |

-0.18 |

0 |

0 |

||

| Fathers rights | 8 |

1,355 |

0.07 |

+0.07 |

0 |

0 |

||

| Immigration control | 3 |

1,329 |

0.06 |

-0.01 |

0 |

0 |

||

| Independents | 74 |

106,934 |

5.18 |

-4.25 |

5 |

-8 |

3.03 |

|

| Total | 470 |

2,065,810 |

100.00 |

0 |

165 |

0 |

100.00 |

Note: Table refers to contested seats; FF also won the one uncontested seat (automatic re-election of Ceann Comhairle), giving it 78 seats out of 166 in the 30th Dáil. Fathers rights and immigration control are not registered parties so their candidates are not officially listed as such. The five independent candidates to win seats received first preference votes of 12,919 (Michael Lowry), 6,779 (Beverley Flynn, not standing in 2011), 5,993 (Jackie Healy-Rae, not standing in 2011), 5,169 (Finian McGrath), and 4,649 (Tony Gregory, died in 2009).

Electorate: 3,110,914. Turnout (valid vote / electorate): 66.41% (+4.30 compared with 2002). Invalid votes 19,435.

If seats had been allocated purely on the basis of total national first preference votes, and if all votes had been cast as they were on 24 May 2007, then the allocation of the 165 seats under the Sainte-Laguë method (generally seen as the 'fairest' since it does not systematically favour either larger or smaller parties) would have been FF 72, FG 47, Lab 17, SF 12, Grn 8, PDs 5, Soc 1, PbP 1, Michael Lowry 1, Beverley Flynn 1. Under the D'Hondt method, which tends to give the benefit of the doubt to larger parties, the figures would have been FF 73, FG 48, Lab 18, SF 12, Grn 8, PDs 4, Soc 1, Michael Lowry 1.

One of the most striking aspects of the 2007 election was a decline in the number of female TDs, from 23 at the end of the life of the 29th Dáil to a mere 22, the same as at the start of the 29th Dáil. With only 13.3 per cent of TDs being female, Ireland continues to occupy a low position in the international league table for gender balance within parliament. Of the 23 women who were members of the 29th Dáil at the time of its dissolution, 14 were re-elected, three retired, and six were defeated. Two previous female TDs returned to the Dáil and they were joined by six first-time female TDs. Whether things should and will be any different in 2011, and what to do if they are not, is a frequent topic of discussion on the Political Reform site.

|

|

|

|

|

Last updated 17 August, 2021 1:13 PM