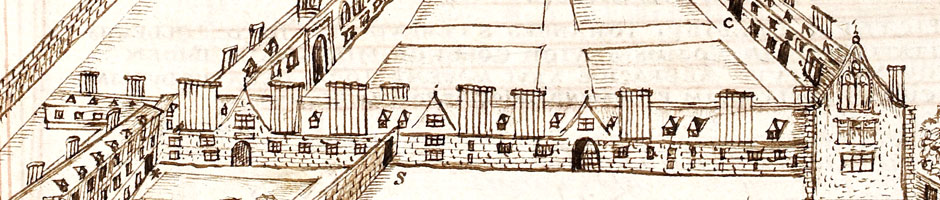

The Old Library

Within 25 years of its foundation in 1592 Trinity College had amassed an impressive library. Over £600 had been subscribed to the College in the

early 1590s by serving officers in Queen Elizabeth’s army in Ireland but payment was deferred until 1601. This money was entrusted to College

Fellows Luke Challoner and James Ussher (afterwards archbishop of Armagh) to travel to London to make book purchases. By 1610 the Library’s

holdings stood at almost 4,000 volumes, and the collection was built up steadily over the

following century.

The English bookseller and author John Dunton visited Trinity College in 1699. In his book The life and errors of John Dunton late citizen of London (1705) he describes how the original Library was housed above the Scholars’ chambers which ran the length of one side of the small Elizabethan square known as the ‘Quadrangle’. It was divided by a partition into inner and outer rooms, and only the Provost, Fellows and resident Bachelors of Divinity had access to the inner library. Dunton described the collection of volumes as ‘a great many choice books’, and he extolled the ‘choice and curious books’ of the great scholar Archbishop Ussher, whose collection came to the College in 1661. On display in this exhibition are some volumes from Ussher’s library, which formed the nucleus of the Library’s medieval manuscripts collection, and was housed behind a lattice‐work division at the west end of the Library.

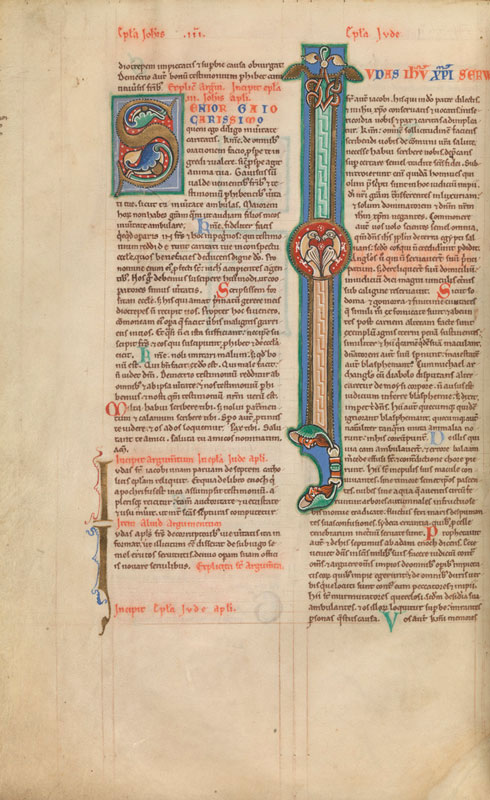

Winchcombe New Testament and Psalter

Winchcombe New Testament and Psalter

Gloucestershire, England, 12th century

This manuscript originated in the Benedictine abbey of Winchcombe and came to Trinity College Library in 1661 as part of

Archbishop James Ussher’s collection.

TCD MS 53 folio 7v

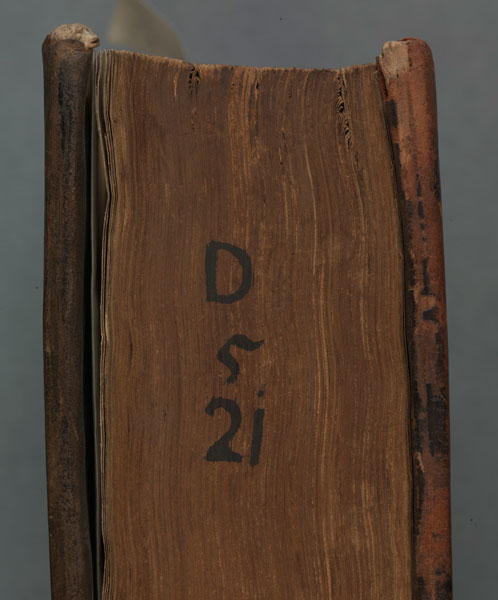

West Dereham Bible

West Dereham Bible

Norfolk, England, 12th century

This is the second volume of a two‐part Bible, possibly produced at the Abbey of St Albans, Hertfordshire, for presentation to the West Dereham

canonry, founded in 1189. It formed part of Archbishop James Ussher’s library.

TCD MS 51 folio 161v

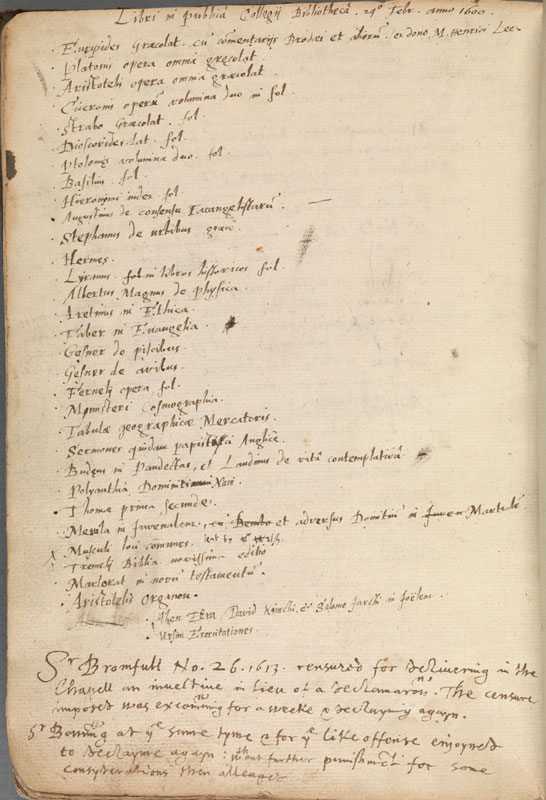

Particular Book of Trinity College

Particular Book of Trinity College

The Particular Book is the earliest extant record of Trinity College. It contains records of receipts and expenses, with resolutions of

the Board and memoranda by various Provosts, dating from the foundation of the College in 1592 up to 1641. This inventory of

books held in the Library, dated 24 February 1600/1601, lists 30 printed books (one is on display in the exhibtion: Aristotle’s Omnia

opera) and ten manuscripts.

TCD MUN/V/1/1 folio 128v

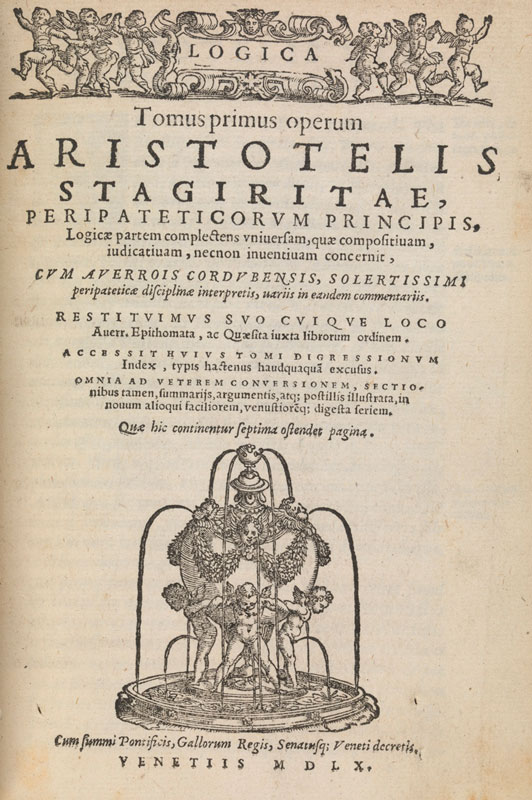

Aristotle Omnia opera

Aristotle Omnia opera

Venice, 1560

Title page of the first volume in an 11‐volume set of Aristotle’s works which appears as the third item in the list of books included in

the Particular Book.

L.m.1

Bookseller’s receipt

Bookseller’s receipt

[1601]

A receipt from bookseller Gregory Seton, of Aldersgate, London

for books sold to Vice‐Provost Luke Challoner on behalf of the

College Library.

TCD MS 2160a/10

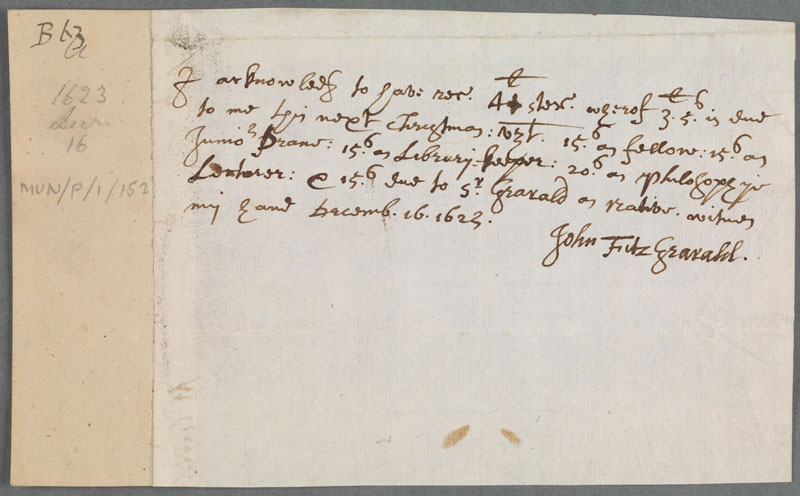

Keeper’s salary

Keeper’s salary

Statement of payments due to John Fitzgerald, including sum of

15 shillings for his service as Library Keeper (1618‐c1624).

TCD MUN P/1/1520

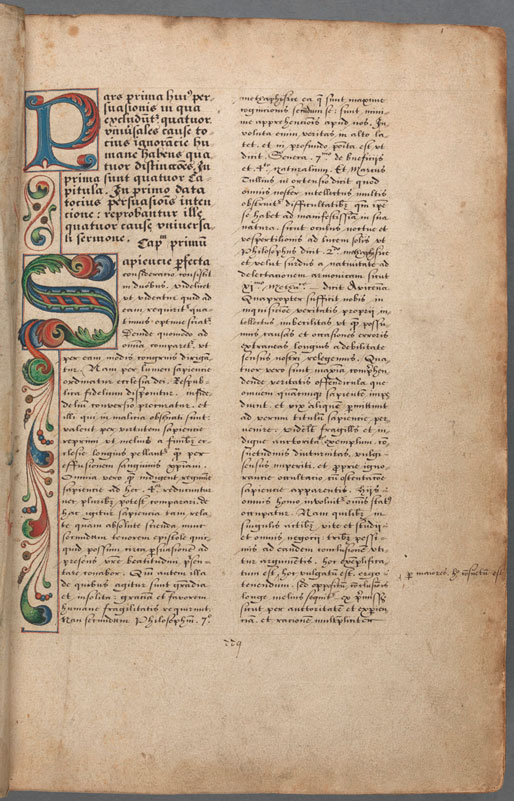

Roger Bacon Opus Majus

Roger Bacon Opus Majus

England, 16th‐17th century

Copy of the 13th‐century philosopher Friar Bacon’s Opus Majus, a treatise – written at the behest of Pope Clement IV – that ranges

over all aspects of natural science, from grammar and logic, to mathematics, physics and philosophy.

TCD MS 381 folio 1

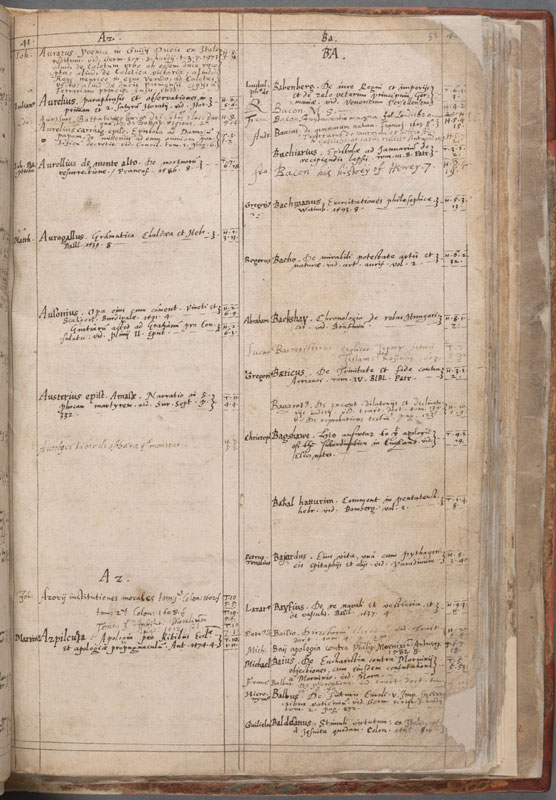

Trinity College Library catalogue

Trinity College Library catalogue

1610

This author catalogue, compiled initially by Ambrose Ussher, the first Library Keeper (1601‐1605), records almost 4,000 works,

including one of the College’s prized manuscripts (TCD MS 381), attributed to Roger Bacon.

TCD MS 2 folio 52r

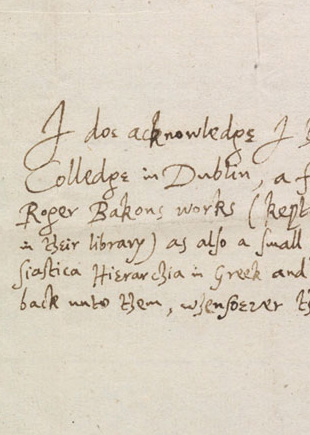

Ussher’s receipt

Ussher’s receipt

This receipt, in Archbishop James Ussher’s hand, records that he borrowed from Trinity College Library ‘a fair manuscript volume of

Roger Bakon’s works … as also a small printed book of Dionysius, his Ecclesiastica Hierarchia in Greek and Latin’. The Bacon

manuscript survives in the collections as TCD MS 381 but the work of Dionysius is no longer present.

TCD MUN/LIB/10/8